What we did: the testing battery

PHASE 1: In the Autumn/Spring term of 2017-18 we saw children twice at their school, for 45 minutes to an hour each time, asking them to complete a series of tasks (see Bibliography for the standardized tests used):

- Memory tasks: to test how much information children could retain and use at a given time, we asked them to repeat series of numbers and short words, forwards and backwards (CELF-4 UK).

- Attention tasks: to assess how well children could focus on a task or a specific piece of information they were asked to carefully listen to a series of sounds, keeping count (TEA-Ch).

- Non-verbal cognitive task: to assess children’s non-verbal abilities they were asked to choose the picture that best completed a pattern, with patterns of increasing complexity and abstraction (WPPSI-IV).

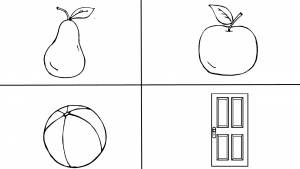

- Vocabulary breadth task: vocabulary breadth can be defined as the number of words a child knows (BPVS-3). To test this, the experimenter showed the child four pictures, and told them a word. The child then chose the picture that matched the word. For example, the child heard “apple”, and had to point to one of the four pictures similar to those in the figure:

Example: “apple”.1

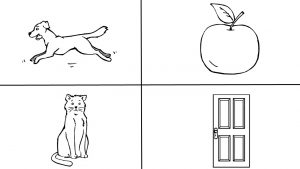

- Vocabulary depth tasks: vocabulary depth can be defined as how much a child knows about a given word, and its connection with other, similar words. In two vocabulary depth tasks, children were asked to choose the synonym – i.e. a word with a similar meaning, or the antonym – i.e. a word with the opposite meaning, for a give word. For example, in the synonym task, given the word “ill”, and the options “dirty, sick or tired”, the child should have chosen “sick”. In the antonym task, given “bad” and the options “pretty, good or slow”, the child should have chosen “good” (Test of Word Knowledge). In a different task, the child was shown a page with three or four pictures, and she was asked to choose the two that went together best, explaining why (CELF-4).

Example: cat and dog go together because they are both animals.1

- Morpho-syntactic tasks: morpho-syntactic knowledge is knowledge about word forms and sentence structure,. i.e. how words are combined to form sentences. For example:

- knowing the difference between “cat” and “cats”

- saying “he reads” and not “he read”

- understanding the difference between “the elephant pushes the girl” and “the elephant is pushed by the girl”

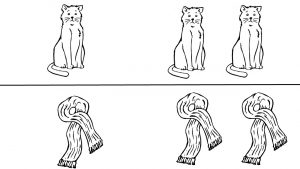

In one task the child and the experimenter looked at pictures together, describing them in turn (CELF-4).

Examples: “Here is one cat, and here are two… (cats)”

“Here is one scarf, and here are two… (scarves)”1

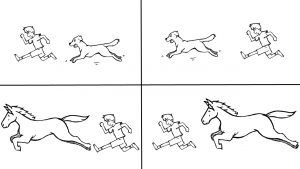

In a second task the child looked at four pictures, and listened to a sentence, and they were asked to choose the best picture for the given sentence (TROG Short).

Example: “The boy is chasing the dog”1

- Inferencing task: inferences are informed guesses that help us to understand a situation when not all of the relevant information is provided explicitly. To assess this ability in children without relying too much on spoken language, we showed each child a sequence of pictures that made up a story. To help the child focus, we described the pictures to her, without giving hints on the characters’ feelings or motivations. For example, given a picture of a cat jumping to catch a butterfly, we only said “Here the cat jumps, and the butterfly flies away”, omitting the link between the two events, to allow children to draw their own conclusions. Children were then asked questions about their interpretation of the events, such as “Why does the cat jump here?” (Task adapted from MAIN)

- Comprehension monitoring task: comprehension monitoring is the ability to keep track of whether we understood what we have listened to, or read. By realising we have not understood a written text, for example, we can go back and re-read the parts that were unclear, and this helps our comprehension. This ability develops slowly in children, and can deeply affect their understanding of a given story.In the comprehension monitoring task, the child was asked to play a computer game, where a dinosaur, described as a trickster, would tell them stories that sometimes would make sense, and sometimes would not. The goal of the game was to avoid being tricked by the dinosaur, by pressing a red button, when the story didn’t make sense, and a green one, when it did.

- Listening comprehension tasks: Listening comprehension, is, broadly speaking, the ability to understand spoken texts such as stories. To assess listening comprehension, we asked children to listen to a few short stories, and answer questions about them, using a standardized task (CELF-4) and a bespoke task.

Alongside direct measures of children’s knowledge of English we asked parents to fill in a questionnaire estimating their children’s exposure to English and to their other language(s) on a daily and weekly basis. The questionnaire included retrospective information from birth and it allowed us to compute a measure of cumulative input in English, a proxy for how much English children have heard in their lives up to the point of testing. The questionnaire was previously used by De Cat, Gusnanto & Serratrice (2017) and by Serratrice & De Cat (2018). Further information about the questionnaire and the calculation of cumulative input available here: https://leedscdu.org/our-research/the-bilingual-language-experience-calculator/

PHASE 2: In the Spring/Summer term of 2018 we saw the same children again, twice, for 45 minutes, asking them to complete a subset of the same tasks used in Phase 1, as well as additional tasks (see Bibliography for the standardized tests used):

- Reading decoding tasks: When a reader encounters a written text, the first task he needs to perform is trying to make sense of the written words. To do so he needs to transform these written elements in oral words. This process is called orthographic-phonological decoding, and broadly corresponds to the ability to read aloud. In English, children read aloud in different ways, for example segmenting a word in its components, reading by analogy or recognising the full word. However, not all these strategies are effective for all types of words: some words follow phonics rules, and can therefore be read by segmentation in smaller parts (e.g. pot and marzipan – they are different in length, but both can be read by reading their single letters out loud), while other words don’t follow these rules (exception words), and therefore require different reading strategies (e.g. ball and machine – reading aloud single letters or digraph would produce an incorrect pronunciation like baal or match-eye-n). To assess reading decoding skills we asked children to read aloud lists of real words, exception words and non-words (words that do not exist but follow the rules of written English), to compare their expertise in using different reading strategies. We used two standardized tests, a timed (TOWRE-2) and a non-timed one (DTWRP).

PHASE 3: In the Autumn/Spring term of 2018/2019 we saw the same children again, twice, for 45 minutes to 1 hour, asking them to complete the same tasks used in Phase 2, as well as one additional task (see Bibliography for the standardized tests used):

- Reading comprehension task: The final goal of reading is understanding the written text. To assess this ability we asked children to read aloud two passages from a standardized reading comprehension test (YARC). At the end of each passage, children were asked questions about what they had read.

Notes:

1 Examples were created for illustrative purposes only. These do not correspond specifically to the items used during testing.

Bibliography:

Bishop, D. V. M. (2003). Test for the Reception of Grammar – Version 2 (TROG-2). London, UK: Harcourt Assessment.

De Cat, C., Gusnanto, A., & Serratrice, L. (2018). Identifying a threshold for the executive function advantage in bilingual children. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(1), 119-151.

Dunn, L. M., Dunn, D. M., & NFER. (2009). British Picture Vocabulary Scale – 3rd ed. (BPVS –3). London: GL Assessment Ltd.

Gagarina, N., Klop, D., Kunnari, S., Tantele, K., Välimaa, T., Balčiūnienė, I., … & Walters, J. (2012). MAIN: Multilingual assessment instrument for narratives. Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft.

Manly, T., Robertson, I.H., Anderson, V., & Nimmo-Smith, I. (1999). TEA-Ch: The Test of Everyday Attention for Children Manual. Bury St. Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test Company Limited.

Semel, E., Wiig, E., & Secord, W. (2006). Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–4th ed. (CELF – 4 UK). London: Pearson.

Serratrice, L., & De Cat, C. (2018). Individual differences in the production of referential expressions: The effect of language proficiency, language exposure and executive function in bilingual and monolingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition.

Snowling, M. J., Stothard, S. E., Clarke, P., Bowyer-Crane, C., Harrington, A., Truelove, E., & Hulme, C. (2009). York Assessment of Reading for Comprehension (YARC). London: GL Assessment.

Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R., & Rashotte, C. (2012). Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE-2). Pearson Clinical Assessment.

Wechsler, D. (2012). Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence—Fourth Edition (WPPSI – IV). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Wiig, E. H., Secord, W. (1992). Test of Word Knowledge. U.S.A.: The Psychological Corporation.