The Engine Room is an arts-led mental health collective based in Reading which run by a core group of around 20 volunteers. The group uses creative methods to develop projects exploring emotions, wellbeing, architecture, construction, and soundscapes in different settings.

The Engine Room works with historically underrepresented groups, including people from ethnic minorities, communities living on low incomes, people experiencing inequalities in accessing education and work, people who neurodiverse or considered to have a disability, refugee communities, people facing addiction, and soldiers living with PTSD. The group’s project within the CLRP focused on the Dee Park Estate in Reading.

Aims

Core research theme: Investigate how sound, ambience and (eco)acoustics can affect the wellbeing and mental health of a community.

‘The Engine Room Sound Laboratory’ (TERSL) project was designed to use art and science to carry out playful, significant, and culturally relevant research with the Dee Park community in Reading, which could have a long-lasting impact on the residents of the estate. Its aims included:

- Explore how soundscapes – both positive and negative – affect community wellbeing

- Build awareness of how sound relates to emotion, memory, space, and identity

- Develop creative tools – such as a sound vessel, fielding recordings, and arts displays – to analyse and archive different lived experiences of place

- Encourage and empower underrepresented communities to influence future housing and regeneration projects by highlighting the sensory impacts of sound and design

Methods, Principles & Practices

The delivery team for TERSL was led by visual artists and community leaders Lisa-Marie Gibbs and Philip Newcombe from The Engine Room, who were supported by Ceara Webster (D&I Adviser, UoR) and Annet Twinokwediga (Architect and MSc Spatial Planning and Development student, UoR), as well as Sally Lloyd-Evans and Alice Mpofu-Coles.

The project was initially developed in response to a series of playful, open-ended prompts, in the form of ‘Questions on a postcard, please’, and ‘Where do all the lost sneezes go?’, which encouraged the Dee Park community to explore and express their ideas of what ‘science’ could mean in everyday life.

Responses to these questions include questions such as:

- Can you measure the sound of emotion held within concrete?

- Could the colours that surround us in the design of housing estates help with a community’s wellbeing?

- The noises on the estate have a really big effect on my concentration. I have autism and hear sounds that are magnified may times. How could design of spaces help this?

- Why are scent and memory so interlinked?

These offered provocation to the team to form a responsive enquiry into the impact of positive and negatives soundscapes on community, particularly relating to the differences between positive and negative soundscapes, how they make participants feel, and how the design of future developments can create healthy soundscapes.

Having been present in and around Dee Park and its community for many years, Lisa-Marie and Philip already had long-standing and trusted relationships with residents in the area, which helped to facilitate this project. Residents were invited to explore the relationships between sound and wellbeing through creative weekly workshops which incorporated a wide range of practices, blending scientific reflection with artistic expression.

In the next phase of the project, community members were equipped with recoding tools such as mobile phones, contact microphones, and field recorders, to collect ambient and personal soundscapes. These sounds came from both everyday environments – radiators, boiling kettles, roadworks – and more imaginative or symbolic sources, such as decommissioned phone boxes, or the clay of Lousehill Copse, which had been dug and then shaped into a sound vessel. The sound vessel itself is a ceramic sculpture created by 57 pairs of hands from across the community, which embodied the tactile, communal spirit of the project and physically captured the wind and the voice of the estate.

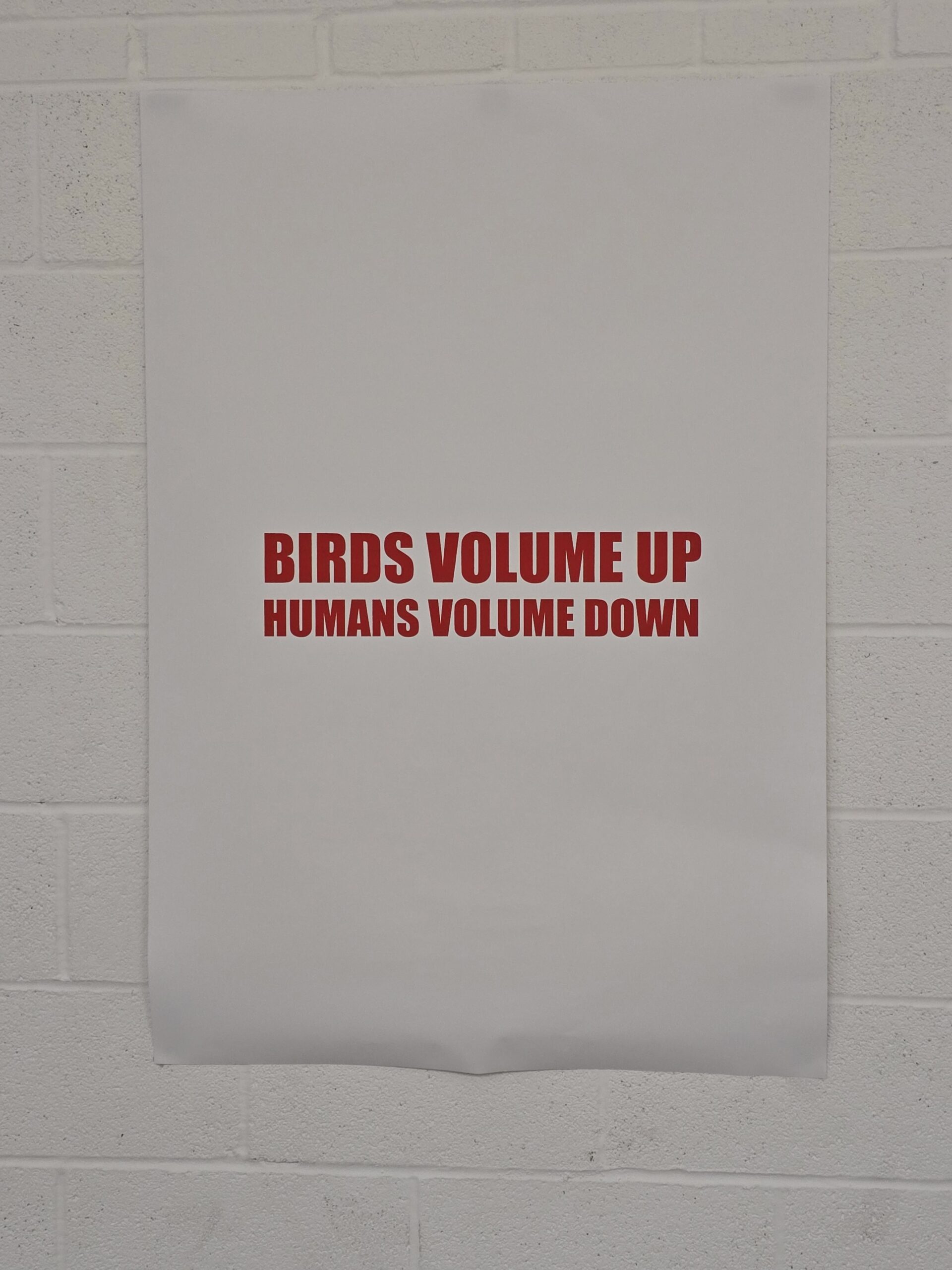

Alongside field recording activities, the team hosted reflective workshops with UoR researchers to explore eco-acoustics and sensory design. Participants were encouraged to think critically about sound in their environment, asking what constitutes a health or harmful soundscape, and how sound contributes to feelings of safety, identity, and belonging. Further creative activities, including a punk-inspired pop-up exhibition Is this Punk? By Jimmy Yoder, further bridged the gap between acoustic science and lived experience.

Outcomes

The project generated a number of powerful outcomes – both tangible and intangible – which emphasised the importance of combining participatory research with creative arts practices. One key outcome was the development of a new, community-informed method for exploring the relationship between soundscapes and mental wellbeing. Rather than treating research as a detached, analytical process, TERSL embedded research in lived experience, asking residents to reflect, record, and reinterpret the sound world around them.

Many participants reported a stronger sense of connection to their surroundings and to one another. Through the creative sessions, they developed a greater awareness of how sound influences mood, memory, and concentration, particularly for residents with sensory or mental health needs. The project also helped share insights to wider audiences through its creative, public-facing outputs. These included an archive of recordings published on SoundCloud, a short film entitled The Estate, which captured the sonic and visual identity of Dee Park across seasons, and various exhibitions and installations that showcased the community’s reflections and creations. The Sound Vessel also became a powerful symbol of the project, both as a sculpture and acoustic archive, shaped by the hands of the community and animated by the Dee Park environment.

These outputs offered an alternative means of documenting the research process and helped participants shape a shared language around wellbeing, sound, and place. The success and creativity of the project and Engine Room’s approach was recognised nationally, when TERSL was awarded a Creative Lives Award, celebrating the ways it enriched the cultural and emotional lives of the Dee Park community.

Future Prospects

The Engine Room and the Dee Park community are keen to build on the momentum of the TERSL project and embed sound-focused research into long-term community development. One clear next step is to carry the finding from this project into ongoing discussions around housing regeneration in the area, with a particular focus on ethical, conscientious development. By using the language and tools developed in the project – particularly the insights around harmful versus healing soundscapes – the community can advocate for more sensory-inclusive urban design. These insights could inform local planning as well as broader conversations around how sound and wellbeing intersect in other built environments.

For researchers and academic institutions, TERSL offers a model which shows how participatory research can be rigorous and joyful at the same time, showing value in being shaped by artistic inquiry and lived experience. Future collaborations should continue to support this interdisciplinary model, where researchers work alongside artists and communities in equitable partnership to co-produce knowledge and action.

Funders and policymakers have a significant role to play in terms of sustainability and scale. TERSL demonstrates that a cultural, community-based infrastructure is a necessity in supporting health, cohesion, social integration and resilience. Long-term investment in participatory, arts-led research should be prioritised not only for its cultural value, but for its capacity to produce meaningful qualitative and quantitative data, influence policy, and transform lives