The Community Led Research Pilot (CLRP) was a collaboration between the University of Reading (UoR), the British Science Association, and community groups across Reading and Slough between 2022 and 2025, funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). The six groups which co-designed projects were Reading Hongkongers, the Integrated Research and Development Centre (IRDC), Engine Room, and TRIYBE, all of which are Reading-based, and Together As One and Slough Anti-Litter Society (SALS), which are both based in Slough. These six groups were fully funded following an Initial activity testing phase, carried out by 13 groups.

The CLRP was designed to put communities at the heart of the research process, aiming to empower groups that are seldom heard and underrepresented to take the lead in co-designing and co-delivering culturally and socially responsive projects alongside a University partner. There were additional aims related to institutional and organisational development, piloting principles and practices for equitable public engagement with research, valuing diverse and seldom heard voices in the research process, and embedding a participatory research approach to achieve social impact. This reflects ongoing activities across Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and funders on their civic responsibilities and the real-world impact of research on people, culture, and the environment.

Despite this increased focus and allocation of funding towards these goals, the infrastructures to enable this work and the awareness and understanding of systemic barriers, power dynamics, and complex challenges remains inconsistent and relatively limited across the sector in the face of a range of evidence including from this pilot. Centring community voices and viewpoints in research whilst also achieving impact is extremely intricate, multifaceted work.

In this summary, the delivery team from University of Reading shares collective reflections from their experiences in the CLRP and more broadly, the delivery of participatory research projects with diverse communities, which has been ongoing at Reading for over 10 years The key themes explored are:

- Identifying, Investigating & Breaking Down Barriers

- Distinctions of Place, Culture & Need

- Valuing Different Knowledge Systems and Lived Experience

- Enabling Structures for Capacity Building

Identifying, Investigating & Breaking Down Barriers

It is essential from the outset of any community-led project to understand the barriers which have prevented public participation in science and research. Beginning a project with this in mind means teams can design structures and safeguarding mechanisms that centre equity, anti-oppression, and truly value new, community-generated knowledge. Key areas of focus here include:

- Time and project structures

- Power dynamics

- Systemic inequalities

- Institutional processes

- Sustainability and legacy

One of the most significant challenges is a lack of time allocated to community research projects, both in terms of overall length and longevity, as well as the time dedicated to crucial phases. Working with diverse communities, particularly when focusing on issues of social and/or health inequalities which carry trauma within them, requires trusted relationships with academics and facilitators. These can only be developed over time through strategically designed activities, participating in a community’s own geographical space without the collection of data, but with a foundation of anti-oppressive practice. The time required to develop meaningful projects responsive to community needs is at odds with cycles of academia and publication requirements for academic progression and promotion, which frequently leads to short-term thinking and cultures of extraction for academic and organisational outputs. The rhythm of communities is different and needs to be taken into account when considering project structures, with a greater emphasis on ‘slow scholarship’.

Outreach, engagement and recruitment is another phase which can take time and requires careful consideration, particularly when matching researchers with community groups. Distinct skillsets are required to work with and safeguard communities in a research setting, and academics working on deadlines, otherwise extractivism can be the result, causing more harm than good. Due to short timescales and limited funding, even once delivery teams have people in place with the appropriate experience and expertise, they are frequently employed on short-term, precarious contracts which does not value their contribution and are not conducive to developing and delivering sustainable, impactful projects. On the community side, the vast majority of community researchers are volunteers, often working on projects outside of their regular working hours or at weekends, so when they are not appropriately remunerated for their time or labour, this can lead to them feeling undervalued by institutions.

Power dynamics within the community, research organisation, funder and university partnerships are another crucial barrier that needs to be addressed and mitigated at the outset. Universities traditionally hold significant power and reach in their regional setting and have the resources and infrastructure to generate impact in research and policy settings. One of the goals of community research should be to redistribute or share this power and infrastructure to support communities to create the necessary changes to address inequalities and generate social impact. This means moving away from a top-down approach, whereby already powerful institutions dictate terms and aims of public engagement, and instead, through co-production, communities are enabled and supported in shaping engagements and the outcomes.

In community engaged research, these power dynamics can be intrinsically linked to systemic inequalities and cultures of extraction. When power structures are traditional and top-down, they perpetuate systemic barriers which disproportionately affect minoritised communities and University colleagues, leading to these groups remaining vulnerable and lacking the control needed in an engagement to truly co-design and deliver projects effectively. These dynamics in a research setting also reflect those in wider society, which are linked to key themes the Participatory Action Research (PAR) team at Reading seeks to address, such as health and ethnic inequalities and the cost-of-living crisis.

How we address power in these engagements connects to institutional processes at universities, which can be prohibitive to community-led research. Universities have understandably stringent finance, procurement, ethics, and Intellectual Property (IP) processes. Still, these often make engaging with community organisations or small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) much harder and require greater adaptability. Finance and procurement processes can be challenging for community partners to navigate, with extensive and inaccessible administration and slow payments both notable frustrations. There is a further tendency for universities to insist upon retaining ownership of intellectual property (IP) generated from research projects, meaning they will largely hold the benefit and legacy of the outputs, as opposed to the community groups who generated the IP from lived experiences, expertise and knowledge. Though universities and funders are beginning on it, ethics in community-university partnerships is also highly complex and moves beyond procedural norms and into an ‘ethics of care’, which is often not reflected in formal institutional protocols or approval processes.

A final challenge related to both time and funding is the extent to which sustainability and legacy of projects are built in from the outset. Due in large part to short-term funding cycles and systematic pressures on academics, it can be extremely difficult to build-in sustainability and long-term benefit to community partners – often, having achieved specific university-centric outcomes, such as producing peer-reviewed papers or evaluation reports, the engagement concludes. These outcomes frequently lead to further funding opportunities or kudos within the sector for the institutions or research organisations, but not for the communities themselves, and they do not serve to decolonise knowledge. If community-engaged research projects are to be equitable, the sustainability and legacy for all partners must be considered from the community perspective as a part of co-production with the institutions and organisations involved.

Distinctions of Place, Culture & Need

The place-based nature of the projects within the CLRP demonstrates something unique about the value of PAR and the needs-led nature of the research. Communities in Reading and Slough have distinct geographical interests and concerns, and experience different challenges, as well as opportunities – the same can be said of communities nationwide. The CLRP illustrated ways to address this by taking a place-based approach so that projects and outcomes were socioeconomically and culturally responsive.

There are several key aspects to this approach:

- Relationship building with communities and local partnerships

- Responsiveness to community interest, concern, and need

- Creative outputs and engagement

- Equality, diversity and inclusion practices embedded

The CLRP helped build an understanding that geographical dynamics mean there is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach to community research, as socio-economic, cultural, linguistic and identity needs differ depending on location and the people involved.

University and community researchers were responsive to the communities’ distinct needs within the CLRP by developing trusted relationships and understanding cultural differences. In the case of the groups in Slough, building these relationships meant extensive attendance at local events and also recognising that they had had little prior engagement with the University, meaning significant emphasis was placed on this phase. It did present challenges, though, particularly in terms of travel for early career researchers and a need to be present outside of regular working hours at times that suited community group engagement and outreach (i.e., evenings and weekends).

The relationship building phase must also be supported by local partnerships. In the CLRP, this came via Reading Voluntary Action (RVA) and Slough Council for Voluntary Services (SCVS), with both organisations providing an essential bridge between institutions and communities, as well as crucial local networks, knowledge and expertise. However, if these organisations are to play a substantial role in these engagements, as they should, they need to have greater autonomy to shape research with communities from the outset, iideally within frameworks that support collaboration.

These local networks and trusted relationships are a pathway for projects to be responsive to community need, interest, and concern, establishing relevant research themes for communities to explore, and offering greater likelihood of a legacy post-project as a result of local partnerships. In the early stages of the CLRP, these themes emerged through an activity testing phase with the groups and included: a strong interest in sustainability, the environment, and connection to nature; health inequalities and wellbeing; social cohesion and sense of belonging and identity in community; and accessibility of research and the language of science. Once these themes were established, communities were then enabled to explore them in inclusive, creative ways which helped to make the projects accessible and engaging to a broader audience.

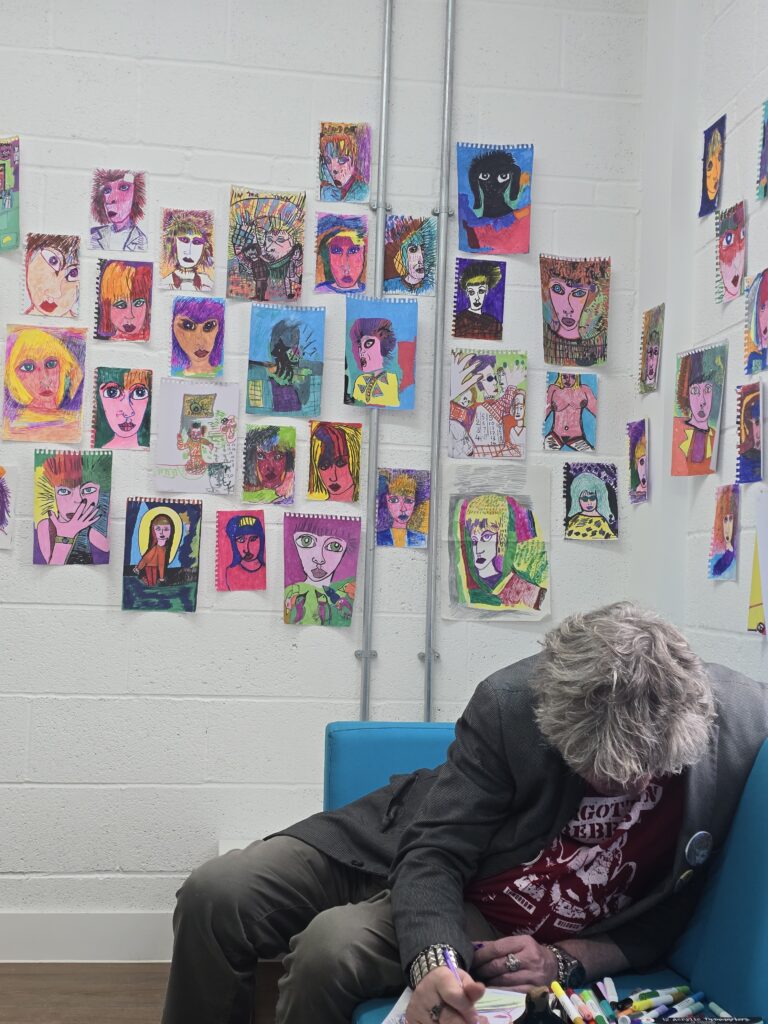

Creativity and accessibility in terms of the outcomes and outputs is another key consideration for community-led projects. Peer-reviewed journal articles and in-depth reports clearly hold value in academia, but there is limited relevance or benefit to these in a community context, particularly if community researchers are not credited as co-authors or the resources are not Open Access. There is an increasing focus on research incorporating creative methods for sharing and dissemination, which is especially important when engaging non-academic communities. This was well-illustrated in the CLRP, with Engine Room using audio, soundscapes and visual arts to explore mental health and wellbeing, TRIYBE engaging communities through podcasts, social media and in-person events, and four projects were supported with storytelling through participatory film in languages that suited the communities.

Being socially and culturally responsive, and responsible, also requires robust equality, diversity, inclusion and accessibility practices to be embedded, underpinned by principles of anti-oppression. To ensure that the intersectionality of community voices and lived experiences are genuinely heard and supported, delivery teams require an understanding of anti-oppressive practice, raising awareness of systems of oppression, power dynamics, oppressive language and behaviours, microaggressions, and inclusive facilitation and engagement techniques for safeguarding purposes.

Valuing Different Knowledge Systems and Lived Experience

PAR and community-engaged research show us the value of the knowledge that communities hold based on their relationships, grassroots action and lived experiences. However, this has frequently been extracted for institutional or organisational benefit, without communities being appropriately recognised, referenced, or credited in the same way as academic knowledge. Through projects with similar aims as the CLRP, there are opportunities to show that both institutions and communities can benefit from equitable co-creation and knowledge exchange, moving towards a collaborative knowledge model, rather than solely academic knowledge. There are several important factors here:

- Valuing, resourcing and acknowledging community expertise

- Challenging hierarchies and power structures

- Collaborative learning and knowledge generation

- Extractive vs relational approaches

For community-centred projects to be successful, it must first be acknowledged that communities hold expertise, relationships and knowledge which universities and science or research stakeholders do not, and that this expertise needs to be equitably resourced. Research needs to be done with and by communities, rather than to or on, to help recognise this. In the CLRP, and many other community-led projects, groups have generated rich, original research questions rooted in lived experience. When this is the case, it enables relevant, real-world outcomes within communities as it directly addresses areas of interest based on existing knowledge and experience. Communities inherently have a better understanding of their own geographical spaces, the languages and rhythms of communities, and they hold trusted relationships – when developing partnerships, this needs to be valued in project structures and delivery.

This is relevant to hierarchical structures within universities and their partnerships, and how they hold knowledge or recognise the value of ‘non-academic’ knowledge and research.

Navigating these structures and acknowledging the value held within communities for knowledge generation reflects a move to a model of collaborative knowledge, as opposed to solely academic knowledge. If this can be done successfully it links to sector-wide aims around the decolonising of knowledge and research, moving away from the dominance of Western or Eurocentric approaches. Further, it illustrates the value of interdisciplinarity when addressing intersectional challenges within society, such as those of health, social, climate, and welfare inequalities. An important step within this is to develop more formalised, equitable processes for crediting community knowledge generation, such as community researchers being co-authors on peer-reviewed papers or journal articles, in the same ways that academics are referenced and credited for their work.

All of the above emphasises the need to embed a relational approach to community-engaged research, as opposed to an extractive approach. Engaging with communities produces value for all stakeholders when a sense of shared purpose, trust and mutual understanding are established, and all contributions are recognised and valued on an equal basis. Projects should help support and nurture community strengths and social impact, validating knowledge and skills at the community level. Incorporating so-called ‘soft skills’ into research approaches and dynamics is significantly underutilised but is absolutely essential when carrying out participatory research.

Enabling Structures for Capacity Building

As indicated throughout this review, there are many systems and structures which are currently prohibitive to carrying out equitable, community-engaged research. However, continuous learning from projects such as the CLRP, one of many community centred initiatives funded by UKRI, show there are ways and means to navigate these barriers and build capacity at both the community and university levels. We highlight a few of these in this final section:

- Training and support

- Capacity building through practice

- Routes to policy engagement

- Evaluation and reflexive feedback

- Building legacy and sustainability

- Sector-wide structures

All community-engaged research projects should be foregrounded by appropriate training, capacity building, and support mechanisms, for both community and university researchers and stakeholders. In the CLRP, responsive training for community groups was provided but would ideally have had more time to firstly, get to know the groups, but also to co-create training packages. Community, early career and academic researcher training needs tailored design in the context of research projects, with particular attention to navigating and addressing power dynamics, use of language, ethics, community development values, PAR methods, and Equality, Diversity, Inclusion and Accessibility (EDIA) and anti-oppression training.

Setting up projects so there is an incubator phase – labelled ‘activity testing’ in the CLRP – can be a helpful means to support groups to trial research ideas and establish areas of interest for communities. Through this process, community groups gained confidence in a research environment, new skills, and connections through establishing a community of practice (CoP). In the CLRP, £2,000 was allocated per group for the activity testing phase, however, more time and financial resource to cover community time could have been allocated to develop this phase further and enable a better flow into the full projects. The establishment of a Community of Practice was another positive aspect following the activity testing, to enable knowledge exchange and discussions around power.

When the CLRP hosted a stakeholder event in the final year of the pilot, participants contributed to collective conversations around areas for potential development or improvement and future opportunities in the context of community research. A point made several times was that finding effective routes to policy engagement and change can be challenging for groups. The systems and language around policy can be inaccessible from a community perspective, so it can be beneficial from the outset of a project to have a dedicated policy professional in place (or able to be seconded onto projects), with connections and experience of that part of the sector.

Alongside policy engagement, an ongoing process of participatory evaluation should be embedded within projects from the outset. Gathering and evaluating the experiences of all partners within a project enables assessment of successes, failures and areas for improvement, increasing the opportunity for organisational or institutional change as a result. There is a risk that research projects can happen in isolation, and that learnings and innovations can be lost if they are not systematically tracked and evaluated. This has particular relevance in community engaged research where there can be high levels of complexity, a dynamic environment in which the research unfolds, and a diversity of stakeholders with varied backgrounds, motivations and interests.

In terms of overall and long-term impact, alongside policy, the stakeholder event highlighted a need for projects of this nature to build-in sustainability and legacy from the outset as much as possible. Often, due to short-term cycles of funding and a quick turnaround for outputs, communities can be left saying, ‘What’s next?’, without clarity on future funding or follow-on activities. Events, CoPs, cross-community networks and relational approaches all provide opportunities to help build in sustainability and legacy, but they need to be appropriately supported – both communities and university teams require more secure funding, longer lead-in times and better support structures generally. There also needs to be greater consideration given to how learning from projects such as this are embedded at institutions, such that projects do not happen in isolation and work is not duplicated across disciplines, which can hinder rather than help genuine progress.

A final point is a broader focus on sector-wide structures. PAR and community-led research as a social science has been sometimes sidelined by some university scholars and funders due to its slow scholarship, and a lack of appreciation for both its rigour and high-quality, real-world impact. Funders should look to fund capacity building and infrastructure development at the community level more consistently, ensuring that PAR has parity with other, more traditional research models. There are ongoing calls for a more civic research culture and new metrics, which place greater emphasis and value on participatory research.

Despite there being ongoing challenges, there is optimism and opportunity around the ongoing development of PAR and community-led research, with influential work being done by many universities in the UK and abroad, UKRI, the BSA, Research England, and National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE), to name a few examples. Stakeholders are invested in bridging the equity gap between academic and community research, making funding fairer and more long-term, and centring communities as equal partners.

This pilot underscores the importance of embedding sustainability, legacy, and capacity-building from the outset – not as optional extras – and treating communities as full partners in decision-making, planning, and dissemination. It also provides valuable lessons for future projects by highlighting the importance of time, trust, anti-oppressive practice, and place-based sensitivity in community-led research, all of which are essential for developing long-term, equitable partnerships. Learning, knowledge exchange, and shared endeavour are all crucial to making this happen.

For more information on Participatory Action Research at University of Reading please contact:

Dr Sally Lloyd-Evans – s.lloyd-evans@reading.ac.uk

Dr Alice Mpofu-Coles – alice.mpofu-coles@reading.ac.uk

Matt Burrows – m.j.burrows@reading.ac.uk