Location

The site of Jemdet Nasr is located about 26 km northeast of the site of Kish in southern Mesopotamia. The site was first discovered in 1925 by the joint team from Oxford University and the Field Museum, Chicago, who were undertaking excavations at Kish. Soon after the discovery, the importance of the site was recognised as it brought to light a distinctive material culture assemblage, leading the archaeological team to coin a new period in the cultural development of the region. The new 'Jemdet Nasr' period fell between the Late Uruk and the Early Dynastic periods, roughly between 3200 and 2900 BC.

The Early Excavations

In the 1920s, a joint team from the Field Museum of Natural History of Chicago and the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford University were carrying out an excavation at the archaeological site of Kish under the direction of Assyriologist Stephen Langdon (Oxford). Kish is an immensely important site in the history of ancient Mesopotamia, where the allegedly founding royal dynasty had first been given the rod and ring of kingship by all-mighty Enlil, the supreme Sumerian god. Unfortunately, the limited standard of excavation of those days and the haphazardly recording of data continues to hinder our understanding of the site and the context in which many of its rich finds were found.

It was this same team that would cursorily explore the nearby site of Jemdet Nasr after one day, a local Arab brought back some unique finds to the Kish site:

"...a strange pottery object, the size and shape of a pork pie, decorated with notches round the upper edge. It was solid. It was weighty. And the top was blackened with marks of burning. We passed it around the little group and put it down; we had not seen such a thing before."

(D. Mackay, 1927; quoted in Matthews 1993, p. 1)

They eventually commenced excavations at the site in 1926 under Langdon's direction. As Matthews (1993, p. 3) points out, Langdon was clearly motivated by the prospect of discovering inscribed tablets, a common theme among early excavations in the region. This focus meant that the standards of excavation and recording methods were significantly lower when compared with contemporary excavations such as those conducted by Woolley and his team at Ur. During the first season in 1926, Langdon excavated a large mud-brick building, presumably the remains of an important administrative seat of power. However, the architecture and context in which the rich finds from this building were poorly recorded. Thanks to Matthews' reassessment of the original plans (now in Oxford) and field notes, we now have a more extensive understanding of Langdon's excavation and the archaeological context in which the finds from the building were found.

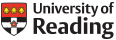

A similar solid stand to the one described in Mackay’s account

The Relevance of the Cultural Assemblage

The finds from Langdon's excavation at Jemdet Nasr came at a time during which archaeologists and philologists were concerned with establishing a full chronological sequence for Southern Mesopotamia. Scholars focused on the unique polychromatic pottery and the proto-cuneiform tables that were found in the large building in Jemdet Nasr. Coupled together, these finds seemed to offer scholars a unique snapshot into the context in which large public institutions and the control of resources (evidenced by the proto-cuneiform tablets and the size and internal organisation of the large building) emerged in the region.

It was thus that the 'Jemdet Nasr culture' became synonymous with the intermediate phase between the preceding period dominated by the massive site of Uruk close to the Arabian Gulf, and the subsequent 'Early Dynastic' period in which Sumerian cities flourished along river channels of the Tigris and Euphrates in the southern alluvium. Due to Langdon's cursory documentation of his work, the term 'Jemdet Nasr culture' or 'Jemdet Nasr period' have been the subject of much discussion over the years, leaving the door open to further exploration of the context in which organised administration and public institutions emerged in the region:

"[A] wider and more significant concern is to explore the possible role or roles of the Jemdet Nasr period or culture, if such can be defined, within the complex and increasingly richly attested processes of social and economic development in Mesopotamia commonly labelled "the rise of civilisation". In this context, chronological and geographical definition may act as a springboard for wider discussion of the place of Jemdet Nasr within the story of the origin and early development of complex, urban, literate civilisation in south Mesopotamia in the late fourth millennium BC."

(Matthews 2002: 7)

One way to investigate how emerging porto-urban communities interacted with each other is through the study of the proto-cuneiform tablets and sealings (lumps of clay with seal impressions on them used to seal vessels and other storage) with very distinctive seal impressions on them, the 'city seals', found at Jemdet Nasr and other important sites including Uruk, Ur, and Šuruppak. The Jemdet Nasr city seal was found on 13 tablets excavated at the site and contains a sequence of city names. The tablets document transactions involving small quantities of dried fruits, grape products and fish. Given the small quantities and the links between the cities named on the tablets and in the seal, these accounts are possibly linked with ceremonial or cultic activities associated with the creation and maintenance of social elites during this period.

Finds from Langdon's excavation of Jemdet Nasr in the Field Museum

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1060899 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1060900 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1060902 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1060904 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1060907 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1060893 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1060894 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1061126 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1061127 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1061135 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1061141 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1061156 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1061170 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1061107 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1134952 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1134952 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1135642 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1135545 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1135547 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1135711 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1388108 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1138277 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1138311 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/153754 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1366070 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1060925 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

© Field Museum of Natural History. CC BY-NC. https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1061053 [Accessed 20 May 2020]

Finds from Langdon's excavation of Jemdet Nasr in the Ashmolean Museum

Tablet with calculation and addition of the areas of five fields

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/461216

Seal impressions on tablet, objects for use in worship

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/485442

Tablet with cuneiform administrative text

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/68896

Model of a boat

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/68892

Vessel sherd with pictographic inscription

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/79785

Pendant in form of nude squatting female

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/139771

The 1988–89 Seasons of Excavation

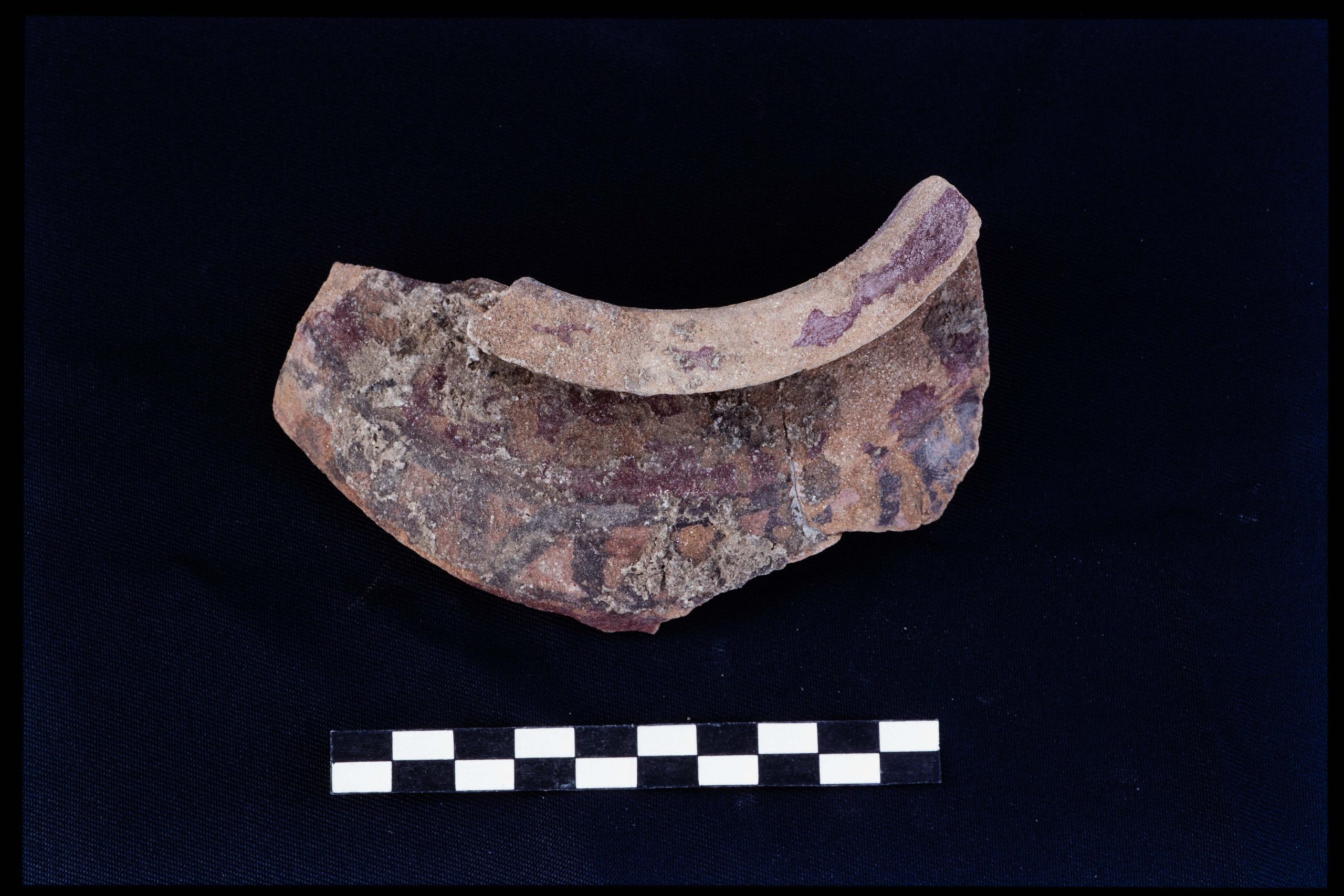

The re-opening of excavations at Jemdet Nasr in 1988 had the prime objective of recontextualising the architecture and finds from the earlier excavations, with the aim of resolving some of the gaps and question marks over its chronology, as well as the layout and function of the large building in which the tablets and polychrome pottery had been excavated in 1926. The new seasons of excavation allowed archaeologists to produce more accurate contour maps and plans of the site, as well as to reassess Langdon's excavation of the large building, located in the NE area of Mound B, and commence investigations of the interrelationships between the phases of occupation at the site: the Late Uruk, Jemdet Nasr, and Early Dynastic I periods.

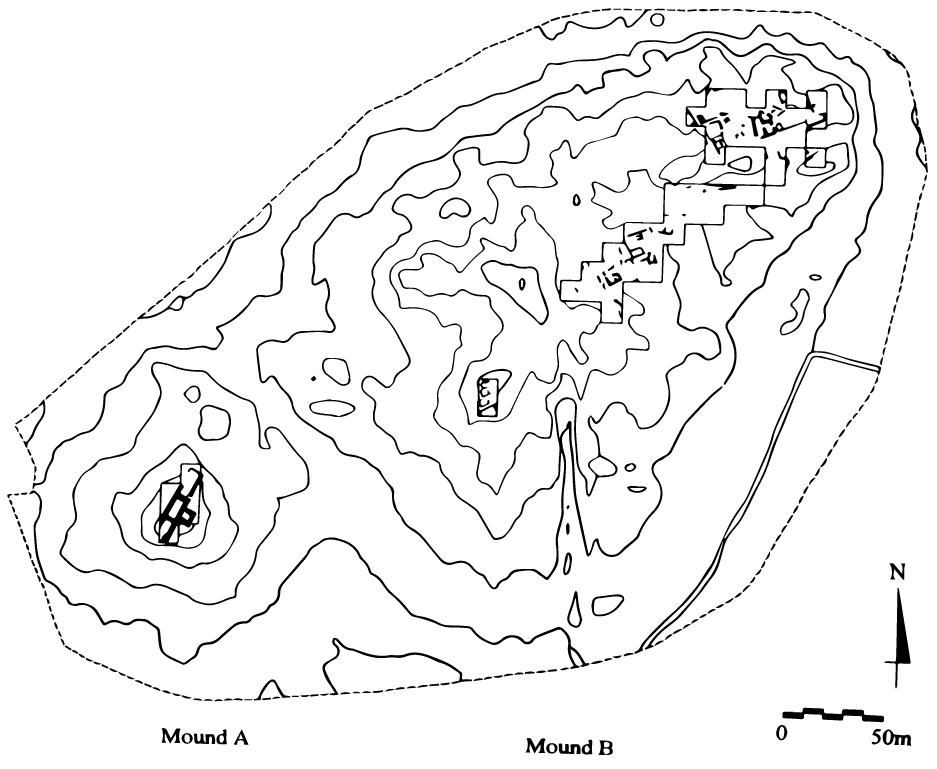

One of the main aims of the 1989 season was to build a site dig-house that would facilitate future work at Jemdet Nasr. The digital archive contains many photographs documenting the construction of the dig house with the assistance of local builders and craftsmen, with some beautiful views of the sunrise at the site. The dig house was completed in December 1989.

The Future of Jemdet Nasr

In 1990, the excavation at Jemdet Nasr was suddenly interrupted due to the onset of the First Gulf War. It has not yet resumed since, despite the site's importance in understanding the emergence of cities, public institutions, and social cooperation. Thankfully, it seems to have survived looting and illegal excavation over the past thirty odd years. Today, the mound of Jemdet Nasr lies quietly among agricultural fields in central Iraq, patiently waiting to reveal more of its secrets. Meanwhile, its legacy is scattered in museums, libraries, and research offices worldwide. There remains much to explore about Jemdet Nasr that will help us clarify and contextualise the significance of the rich findings from the early excavations by expanding on the results of the 1988 and 1989 seasons. There is also much that remains to be explored about what we already know about the site and its socio-political context that goes beyond the site itself. We shall leave our field books open on the site of Jemdet Nasr, and express, in Roger Matthews' words,

"...the sincere hope that the site will not have to undergo another hiatus of sixty years, as it did after the 1928 season, before excavations and explorations can once more be restarted at the site and in its surroundings".

(Matthews 2002: ix)