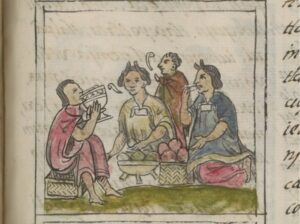

Figure1 Feast of Ixcozauhqui (‘Yellow Face’), deity of fire. Digital Florentine Codex/Códice Florentino Digital, edited by Kim N. Richter and Alicia Maria Houtrouw, “Book 2: The Ceremonies”, fol. 105r, Getty Research Institute, 2023. https://florentinecodex.getty.edu/en/book/2/folio/105r/images/2707bd

‘…to engage in comparisons is as delicious as having a good meal’ (Sahagún 2023 [1575-1577]: Book 4, The Soothsayers, fol. 73v, Spanish column)

Introduction:

The colophon statement, from the Florentine Codex, continues as an admonition against covering the same debates in the same way, too many times, warning that repetitive dialogue loses all flavour and interest. Much innovative, delicious comparison will be in store during a roundtable discussion in the Sorby Room of the Wager Building on 20 June, beginning at 15:00 and followed by an R-LAC sponsored reception.

The roundtable will cover examples ranging across Latin America, from sixteenth-century La Florida (today’s US Southeast) south to the tip of the Southern Cone and across the Caribbean. The discussion will debate the historical roots of challenges facing food systems in Latin America and lessons to be learnt from Indigenous people of the region. The roundtable includes a stellar group of scholars—a guarantee that the discussion will be fresh, exciting, and ‘tasty.’ Discussants from R-LAC include Andrew Wade (Geography & Environmental Science) and Nick Branch (Geography & Environmental Science) as well as Rebecca Earle (History, University of Warwick).

Invited scholars from UK and US institutions will share their forthcoming research on a tantalizing variety of food-related topics. The visiting scholars for the roundtable are Joshua Fitzgerald (Cambridge University), Elizabeth Gansen (Grand Valley State University), Mario Graña Taborelli (UCL), Pax Johnson (University of West Florida), Katy Kole de Peralta (Arizona State University), Estelle Praet (British Museum), and Erin Stone (University of West Florida). A brief summary of research will give a sample of the themes and approaches for the event.

Breakthrough Studies:

A recurring subject of Spanish sixteenth-century narratives is food. Food was a daily challenge and constant need for colonists and Indigenous residents alike, and settler colonial interactions intensified anxieties about food production, distribution, and consumption. Those concerns have continued in the face of climate change and environmental degradation in some cases due to farming practices. Climate- and human-induced disruptions threatened both well-established and new systems of daily sustenance in Early Modern Latin America and the Caribbean. At the same time, colonial encounters introduced culinary worlds to new places and peoples, engendering everything from disgust to delight. Within these complicated, entangled dynamics, Spanish dietary fragility and stubbornness can equally be understood as declarations of Native sovereignty, decisions about whether or not to show hospitality and charity. Native lore, practices of preparing foodstuffs and medicinal remedies, and other practical knowledge permeate Spanish accounts, while archaeological evidence gives a detailed view of such practices and their effects. Taken together, three strong themes are throughlines that link diverse scholarship on food in Latin America to contemporary concerns: seasonality; environmental and culinary diversity; and sustainability. A brief summary of roundtable contributions to these themes will give a taste of likely topics to arise in the discussions on 20 June.

Seasonality

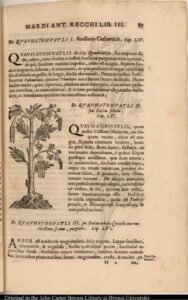

Colonist settlement practices relating to food production and storage had inherent vulnerabilities to seasonal change. The sixteenth century was an initial phase of global shifts in food production and supply that has expanded and grown since, partly to thwart seasonality in market availability. For example, Elizabeth Gansen focuses on the Caribbean as described by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo’s sixteenth-century writings. Oviedo praises the native grown cañafístola, which is “brought to Spain in large quantities and from there it is taken to many parts of the world” (Figure 2). This international demand fostered changes in agricultural practices towards colonist intensification and domestication of what was a local wild tree. Gansen’s work reconstructs the environmental and human loss of colonization, with cañafistola an example.

Figure 2 De Quauhayohuatli II. seu Cassia fistula. Francisco Hernández (1651) Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium mexicanorum historia. Image courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Another aspect of seasonality is cultural and spiritual. Joshua Fitzgerald’s research offers a deep dive into Central Mexican Nahuatl ritual practices relating to amaranth and chia. Crafting, displaying, and eating handmade sacred art known as tepictoton, or “small molded ones” made of nourishing amaranth seed dough called tzoalli was a seasonal ritual practice to create an altar or shrine to commemorate the dead. The tepictoton had three parts: the most interior portion had amaranth-dough figures modelled to resemble actual living or dead people that were encased in a domed, mountain-like exterior shell. This shell was decorated with paint, appliques, and ornamentation such as teeth of gourd seeds and eyes of black beans to identify the mini-mountain effigy with a particular deity. Fitzgerald notes that the amaranth seed dough was a chief ingredient in worship that the people of Mexico enjoyed, for millennia in various forms, from dried cakes to soupy atoles. These amaranth and chia-related practices are important examples of cultural and agricultural resilience despite undermining economic, environmental, and social forces.

Spanish diet endeavoured to stay true to Christian, Catholic beliefs. The food historian Carolyn Nadeau writes brilliantly about the complexities of the Early Modern Spanish diet and food preferences as seen through Spanish literature and cookery books. She found that Domingo Hernandez de Maceras’s Libro del arte de cocina wrote nearly double the recipes on raised and hunted animals and fish than on gathered and cultivated vegetable products. In Muslim and Jewish culinary traditions so important in Early Modern Spain, particular parts of the animal matter, too. These food preferences, some of which have been maintained over hundreds of years, have environmental and economic impacts, especially when exported to new environments in Latin America.

Environmental and culinary diversity

While food preferences can lead to dramatic environmental change, they can also have a positive effect of enhancing culinary diversity. I am evaluating acts of hospitality—especially what, when, and how food was served—for what they reveal about sixteenth-century Indigenous culinary landscapes in today’s US Southeast. During Hernando de Soto’s 1540 entrada and Juan Pardo’s 1579 establishment of forts and Spanish towns in today’s North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi, Indigenous communities made decisions about whether to welcome and support the newcomers. Archaeological evidence from sites in the Ridge-and-Valley portion of these engagements and chronicles offer a view of Indigenous food preferences and values, including how political boundaries were marked with food.

Another view into Indigenous culinary diversity is through the biochemistry of archaeological remains of food containers and dishes for serving. Estelle Praet is conducting innovative studies of food and drink residues on fifteenth- to seventeenth-century Indigenous low-fired earthenware ceramics from Mexico and Central America. Her research focuses particularly on the presence of cacao, which was and continues to be a crucial part of Mesoamerican diet and cultural value systems. Biochemical studies can reveal culinary diversity and changes in food preparation and consumption over time.

What about the relationship of food security and culinary diversity? Consuming some kinds or parts of foods and not others can be a factor in food precarity. Food scarcity can at times be contextual and socially constructed, while other times a result of environmental devastation. Are edible, nutritious foods available, but consist of ingredients or forms that are culturally unacceptable? Scarcity can often result from a lack of food sovereignty, the right to nutritious, culturally appropriate food, as well as control over food production, distribution, and consumption; where the food comes from, who does the work, how it is prepared and distributed is as important as the substances themselves.

Pax Johnson and Erin Stone, both working on examples from sixteenth-century La Florida, illuminate points of conflict between Ideals of Spanish versus local Indigenous diet. Stone describes how French settlers in Florida had traded everything possible—the shirts off their backs—with local Indigenous residents (Timucua) to survive. Though these Protestant settlers aimed to make Florida home, it is clear they did not manage to raise their own food. Katy Kole de Peralta evaluates evidence of the Spanish attempt to colonize one of the most extreme environments in South America: the northern bank along the Strait of Magellan, nicknamed “Port Famine.” Elisabeth Gansen describes Spanish cultivation methods of irrigation, grafting, pruning, manuring, and plowing, all good to cultivate the beans, turnips, quinces, and hawthorn that Katy Kole de Peralta notes for Port Famine and the bread, wine, olive oil, and meat Pax Johnson assesses from archaeological evidence in Florida. The British corsair provisions mentioned in the Straits of Magellan accounts record vinegar, rotten tuna, bacon, cheese, and flour also give a view of staple European as foods fit for long sea journeys. These imports had differing degrees of success and environmental costs that continue to impact Latin America and the Caribbean.

Historian Katy Kole de Peralta urges critique of Spanish claims of starvation and misery. What was the demographic and/or environmental context at the time? The evidence reveals a strategy for acquisition rather than environmental calamity. Spanish accounts often describe villages and fertile, cultivated agricultural lands, yet end with the conclusion that such places should be declared tierras baldias or realengas (unpopulated and unimproved), making them candidates for state seizure. This strategy has early medieval roots—the Cistercians did the same, using nearly the same language, in Wales. Spanish objections to local foods Erin Stone identifies in sixteenth-century accounts of La Florida echo complaints of other Spanish entradas. Worries about food quality and abundance are constant. Stone, however, assesses a surprising detail included as an unremarkable comment: consuming a French Protestant prisoner due to lack of food.

Sustainability

One kind of sustainability is political and social, and at the center of it all is food. A consistent theme in each scholar’s work is that often monarchies did not prioritize colonies politically or financially enough to guarantee an ability to overcome early challenges. A major failure of colonists was to establish enduring alliances with local Indigenous communities. For example, Mario Graña Taborelli investigates the foundation and settlement of three Spanish villages in the Charcas frontier between Bolivia and Argentina—Santiago de la Frontera de Tomina, San Miguel de la Laguna and San Juan de la Frontera de Paspaya—in the second half of the sixteenth century. Establishing these settlements was a process that involved various groups and multiple agencies, including Spanish and Indigenous Andean, Guarani-speaking Chiriguanaes, as well as other communities. Graña Taborelli observes that Indigenous populations accommodated and adapted by assimilating such villages and their authorities in their own fashion. He points out that this evidence informs understanding of present-day geographical, political and cultural frontiers in Latin America and modern-day localism and regionalism. He invites us to re-think ongoing debates about the presence of the state, governance, and legal compliance in geographies that are still remote across Latin America.

A critical realm of sustainability is environmental. How did Spanish-introduced plants and animals complement or conflict with the Indigenous staple foods such as palms, herbs, and shellfish, fish, and oysters? Sugar, milk, and oranges appear quickly in sixteenth-century Mesoamerican language medical incantations and vocabularies, indicating rapid changes in plant species, farming practices, and consuming habits. Recent ethnographic research by Edward F. Fischer and Peter Benson (Broccoli and Desire) shows that Highland Maya communities in Guatemala grow broccoli they do not eat, even when they cannot sell it for export. The replacement, displacement, and marginalization of Indigenous food systems of farming and gathering for globalized export commodity foods makes farming communities vulnerable to food insecurity.

Long-term sustainability is a major theme for two of the roundtable discussants, Nick Branch and Andrew Wade, who both contribute to the project ‘Climate Resilience and Food Production in Peru’ (CROPP), which identifies the water used by agriculture and consequent water availability, now and in the future in the Cordillera Blanca and Cordillera Negra.

Methodology:

The methodologies employed by the roundtable participants are diverse. Both physical remains and documentary and visual sources give insight into food systems of the past and present. Physical remains include the fields, agroforests, and wild terrestrial and maritime/lacustrine landscapes that are apt for spatial modelling. Traces of plants and animals or soil changes that indicate farming or gathering practices or parts of meals range from biochemical residues, soil chemistry and quality, pollen profiles, and faunal and plant part remains, all of which can indicate where, how, and with what consequences people obtain nourishment. Likewise, tools for cultivation and harvest can indicate changes in food-related technology over time.

Documentary sources of maps, legal wrangling, vocabularies, and chronicles help us better understand not just Spanish dilemmas, but also the richness and resilience of Indigenous life.

The Impact of the research on policy and practice:

The diversity of contexts, methodologies, and perspectives brought together by the roundtable have the potential to bring out important new insights on current dilemmas about food systems. The firm focus on Indigenous experience and values re-centres debates to recognize a long legacy of experience and knowledge and decolonise policies and practice for food production, distribution, and consumption.

Future Directions:

We plan for the contributions to the roundtable and workshop to be published as a volume. The roundtable on 20 June is a chance to debate ideas to enhance and help shape the future publication.

Key Publications (discussants):

- Branch, N. , Ferreira, F. , Lane, K. , Wade, A. , Walsh, D. , Handley, J. , Herrera, A. , Rodda, H. , Simmonds, M. , Meddens, F. , Black, S. (2023) Adaptive capacity of farming communities to climate change in the Peruvian Andes: past, present and future (preliminary findings of the ACCESS project). Revista de Glaciares y Ecosistemas de Montaña , 8 pp. 51-67.

- Earle R. The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. Cambridge University Press; 2012.

- Earle R. Feeding the People: The Politics of the Potato. Cambridge University Press; 2020.

- Handley, J., Branch, N., Meddens, F., Simmonds, M., Iriarte, J. (2023) Pre-Hispanic terrace agricultural practices and long-distance transfer of plant taxa in the southern-central Peruvian Andes revealed by phytolith and pollen analysis. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany ISSN: 0939-6314 | doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00334-023-00946-w

About the author:

Dr Katie Sampeck is a 2023-2026 British Academy Global Professor of Historical Archaeology at the University of Reading. She uses multidisciplinary approaches to investigate topics including taste, cultural landscapes, literacy, economic systems in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, Spanish colonialism, the African diaspora in Latin America, and global commerce in the Early Modern world. She has devoted years of archaeological and historical research to understanding the cultural history of chocolate. She co-edited, with Stacey Schwartzkopf, the 2017 volume Substance and Seduction: Ingested Commodities in Early Modern Mesoamerica, published by University of Texas Press. Forthcoming works include Rich: Cacao Money in Mesoamerica and Afro-Latin American Archaeology: An Introduction.