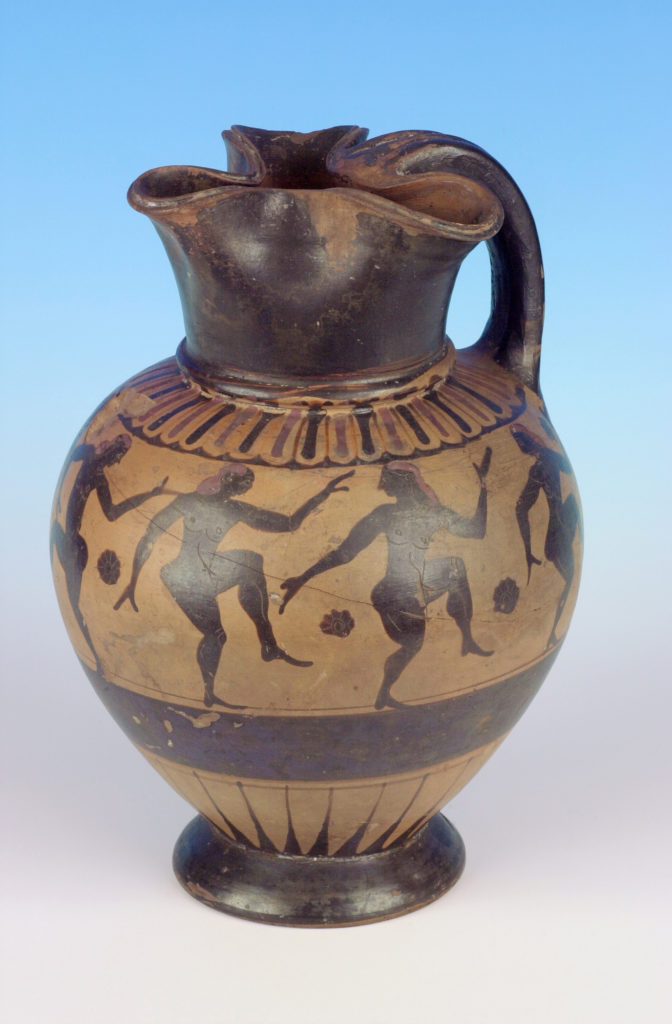

The ancient Greeks left numerous and varied representations of dancing – or at least of what we might understand as the visual recording of movement – on wall frescoes, reliefs, pots, statuettes, etc. Although we lack a written or pictorial catalogue of which steps should be performed for a specific dance, the images that have been recovered from ancient Greece – at different times and in different geographical spots – can tell us what dancing looked like.

When analysing these images, we need to consider that they are not faithful representations of movements performed by professional dancers or by worshippers in a ritual: while they could be inspired by nature – as most ancient Greek art was – these depictions are regulated by a series of conventions and formulas that make up the visual language of this ancient society. Moreover, restrictions of the artistic medium should not be disregarded: translating the kinetic element to a two-dimensional plane (paintings, reliefs) or even to a static three-dimensional one (sculptures, figurines) required a codification of movement, a tacit agreement between producers (artisans/sculptors/painters) and audience (customers, worshippers) which conveyed the message of dancing.

Despite the number of dancing renditions from ancient Greece, the imagery was quite restricted in its scope, there was a limited repertoire to choose from, with few innovations and lots of rearrangements of already existing patterns.[1] The re-use of patterns means that some scenes might be tricky to read: people can be dancing but they can also be running; they could be performing an athletic dance or they can be just jumping to avoid an enemy. Naturally, the presence of musicians playing the aulos, tympanon or lyre would make dancing more evident.

Artisans used already established postures and gestures to convey the sense of dancing. Few depictions carry some sort of inscription that allow us to identify and prove that what it is represented is actually a dance.[2] One could argue that context would clarify the situation but, for example, if we pay attention to scenes of satyrs and nymphs, the first could be chasing the second or they could all be part of Dionysus’ dancing entourage. Context, somehow, is as ambiguous as the scene itself.

Dancing or running?

Chorus dancing could be arguably easy to spot when all figures seem to be in a circle or a line, holding hands or one another’s wrists (epi karpoi grasp) and the position of the arms, with flexed elbows downwards. Vigorous movements like turns are usually indicated by the whirl of a dress or long garments, while highlighted buttocks are linked to komos dancers.

As for the functions of these representations – whether they were especially commissioned or mass-produced – they could be united under the umbrella of “mimicking devices”. Depiction of people dancing evoked a real dance, a dance once performed, either as a form of worship (votives found in temples), a mourning ritual (funerary goods), a private celebration (recreation of entertainment), or public festivities (processions). This may be, however, an oversimplification of the semiotic intention of these representations: we have already established that dancing depictions are stereotyped and codified according to certain conventions, so what they lack in authenticity they could make up with symbolism.[3] They could be more than a non-verbal analogy but a reflection of the experience of dancing itself – of the words sung, the music played, of the feelings that were shared.[4]

[1] Lawler 1947:346; Naerebout 1995:28-31.

[2] For example, Pyrrhias’ aryballos from Corinth with a boy performing a high jump with a text reading Pyrrhias prochoreuomenos. See Frankel 1912, Kossatz-Deissman 1991.

[3] Naerebout 1995:34-35.

[4] Weiss 2020:167.