By Jeremy Burchadt

During the first UK lockdown this Spring, many people ventured out into the countryside who would never normally do so. Walking over the usually deserted Pewsey Downs in late May, I met dozens of walkers and cyclists, while paragliders swooshed past overhead, and the same was true, minus the paragliders, on Ladle Hill a fortnight earlier. It wasn’t just the numbers – as a regular walker you get used to seeing certain sorts of people out in the English countryside, mainly middle-aged and white. After the lockdown began, I noticed many more people in their teens and twenties, many more families and greater ethnic diversity. Ironically and exhilaratingly, the lockdown unlocked the countryside for millions of people who had previously been or felt excluded from it, that it was in some sense not available to them, ‘not theirs’. The Landscape Research Group has been deeply concerned with this theme for years. Thinking about how we can democratize landscapes and landscape decision-making to open it up to hitherto excluded or marginalized groups and individuals is also central to Changing Landscapes, Changing Lives, the Arts & Humanities Research Council network Paul Readman (King’s College London) and I convene. It’s a theme that runs through everything we do and will be the explicit focus of our second symposium, ‘Whose Landscapes?’, which will feature the work of artist, photographer and network member Ingrid Pollard.

On closer inspection, however, perhaps the ‘unlocking of the countryside’ during the first lockdown went less far than met the eye. The multiple causes of differential access did not magically evaporate – where you live, whether you have a car, know how to read an OS map, are used to farm animals and many deeper-lying influences too. Hence people flocked to urban green spaces, riverside paths, well-known local beauty spots and the national parks in far greater numbers than to the ‘deep’ countryside. In a pandemic-stricken world, this brought new problems – how can you maintain social distancing on a narrow footpath if hundreds of other walkers are traipsing along it in both directions? Would we all be safer back at home – has the pandemic turned the stereotypically Victorian notion that fresh air is healthy on its head? But more acutely it also raised familiar conflicts in new guises. In the first few weeks of the lockdown, Derbyshire Constabulary controversially used drones to shame ramblers who they claimed were breaking the government’s rules, Lancashire Police turned back a family driving from London to the Lake District and relations between rural residents and urban visitors became increasingly fraught. Car parks were closed, roads blocked and a rash of improvised notices, ranging from the studiously polite to the gratuitously offensive, appeared on trees, gates and signposts. One widely circulated photo showed a vehicle and trailer blocking access to Lake Bala, Snowdonia, with ‘GO HOME idiots – Covid-19’ spray-painted across them. Other messages made the same point less abrasively.

Although the pandemic has given them a new twist, these tensions between insiders and outsiders have a long history in rural England. Cyril Joad’s The Untutored Townsman’s Invasion of the Country (1946) was in fact more sympathetic to access than its memorably provocative title might suggest, but it reflected widespread anxiety about noise, litter and pollution in connection with the rising popularity of the countryside among the ‘wrong sort of people’ in the mid-twentieth century. These concerns underpinned the introduction of the Country Code in 1951. They also informed the creation of Country Parks under the 1968 Countryside Act. Country Parks were intended as ‘honey pots’ to draw and contain urban visitors, preventing them from intruding into the wider countryside. This deep suspicion, even scarcely veiled hostility, to those (stereotypically urban and working class) thought ‘not to belong’ in the countryside has never really gone away. It represents a rather extreme form of ‘othering’, seen in particularly virulent form in the Countryside Movement protests of the early 2000s (‘Say No to the Urban Jackboot’). Until we are able to achieve a more gracious, welcoming mutual understanding it is difficult to see how problems of overcrowding, littering, path erosion and traffic congestion in the honeypot locations to which visitors are purposely channelled can be overcome. We need a conceptual breakthrough, recognizing that the whole countryside can be a recreational as well as an agricultural resource, analogous to the one Joseph Addison achieved for landscape gardening when he asked in a celebrated 1712 Spectator paper ‘Why may not a whole estate be thrown into a kind of garden by frequent plantations, that may turn as much to the profit as the pleasures of the owner?’

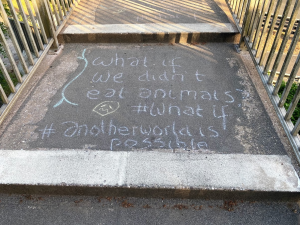

In one sense, after all, whether we are residents or visitors, we are all intruders in the landscape. That, again, became vividly apparent during the first lockdown. Wildlife flourished – out on my walks, I noticed that normally shy and retiring species such as Brown Hares and Fallow Deer had become emboldened, even insouciant. Suddenly, one could gauge how overbearing the pressure of human activity is in ‘normal’ times, squeezing other animals with whom we share our planet to the hidden margins of the landscape. Roads and even skies were quiet, the air was clean – behold a vision of nature restored! Many, especially young people, began to ask what kind of normal we wanted to return to, vividly brought home to me by the chalk graffiti that appeared overnight on the footbridge across the motorway near where we live:

The pandemic’s transformation of the landscape, an unanticipated, even serendipitous, by-product of the lockdown forced upon us, opened up profound questions and perhaps new possibilities about the way we live, what kind of society we are, and our relationship to the non-human world around us.