This blog post is written by Dr. Holly Joseph (Associate Professor of Language Education and Literacy Development at the University of Reading’s Institute of Education). It draws from her recently published co-authored paper based on a research project, which examined the effect of semantic diversity on word learning during reading in children. Her co-author is Kate Nation (Professor of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford).

Let Dr. Joseph know what you think of this blog post on Twitter by tagging her (@drhollyjoseph) in your tweets.

Context

Before children start school, they learn new words through spoken language, mostly by listening to and interacting with their main caregivers. However, this changes once they have learned to read, and we know that from around age 9, children learn most new words through reading. Although we know this is the case, we know very little about how they do this, and what helps them to learn new words meanings efficiently. Learning new word meanings is a complex and protracted process as it takes many encounters with a word to develop a good understanding of what it means and how that might change in different contexts.

Imagine, for example, that you have never encountered the word ‘benign’ before. The first time you encounter it, it is in the context of a medical procedure so you know it has something to do with health. The second time you read it, it is in an article about cancer so you can be a little more confident that it relates to health, and specifically cancer. You may have another five encounters with the word ‘benign’ in similar contexts and begin to build up a pretty good representation of its meaning: that it refers to tumours that are not cancerous for example. But then one day, you are reading about history and you read about a benign ruler. On another occasion, you are reading about climate and read about ‘benign weather’. These encounters with the word in different contexts tell you that the meaning of benign is not restricted to health but can used in other contexts to mean something like harmless. It is only when you have read the word benign in these different contexts that you can build up a really good understanding of what it means.

Research design

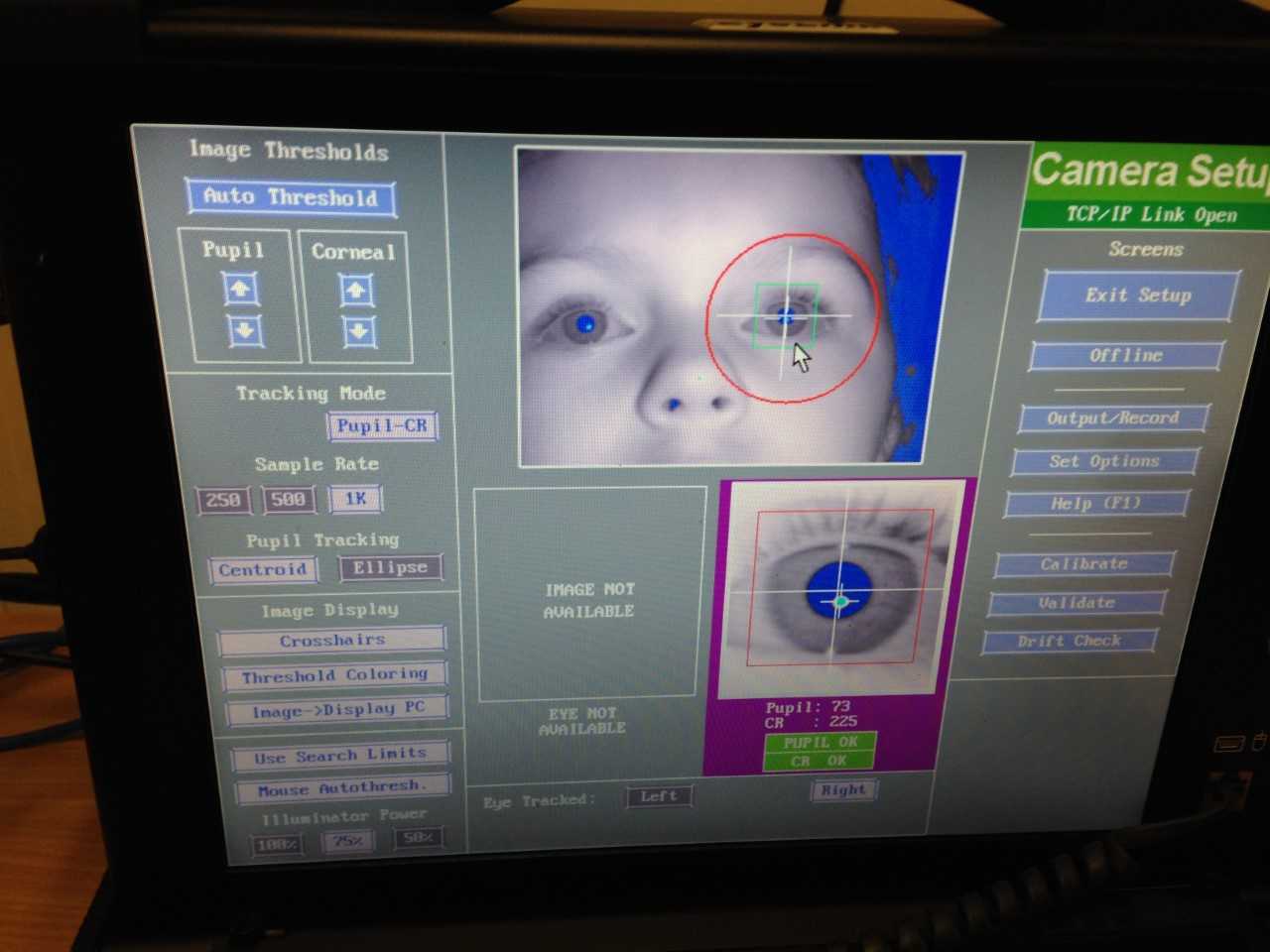

This study used eye tracking to see what children do when they encounter a new word during reading to try and work out its meaning from the context it is in. Our contexts were either very similar (e.g. medical contexts) or varied (weather, history, medical), and we were interested in whether reading the word in varied contexts would help children to learn its meaning better than in similar contexts. We measured how long 40 children (aged 10-11) needed to read six new words (such as languished, confabulated and exacerbated) in our two different types of context over ten encounters. We were confident that reading times would reduce over the course of the ten encounters but what we were really interested in was whether they would reduce more dramatically when the contexts were more varied, and whether this would be the case especially for children with good reading comprehension skills.

Key findings

Our results showed that reading times on the new words decreased with each encounter for all children, but especially for those with good reading comprehension skills. We also found that although reading times did not reduce more in the varied than similar contexts overall, children with better comprehension skills showed a greater reduction in reading times for words in varied contexts than poorer comprehenders. This suggests that children with better reading comprehension skill are more sensitive to context and may have the potential to learn more from contexts that are more varied and therefore potentially more informative. These findings sit well with so-called Matthew effects in reading, whereby children who are good readers increase their vocabulary faster hence widening the gap in reading skill between them and poorer readers over time.

Key messages and future research directions

What are the messages for practice? Well, although we should not take too much from a single study, the results suggest that for children with poorer reading skills, just exposing them to vocabulary through reading may not be enough; explicit instruction (which we know results in better learning) may be particularly important for these children. Pre-teaching vocabulary before a reading task is something many teachers routinely do, and this study suggests that this will be particularly beneficial for those children who struggle to understand what they read. The next question, of course, is what we can do to help poorer comprehenders to make good use of context and become more efficient word learners, and this is something we hope to address in future studies.

Further reading: