Rebecca Bullard writes:

One of my current research projects focuses on eighteenth-century epitaphs. I’m interested in what memorial inscriptions can tell us about the values and beliefs of the people who commissioned them. I’m also fascinated by the ways in which writers and editors in the eighteenth century put together collections of epitaphs in printed anthologies. One such collection is Monumenta Anglicana, a five-volumes set of printed epitaphs published between 1717 and 1719 by John Le Neve, an English antiquarian.

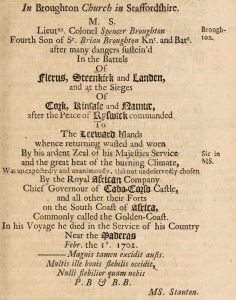

While I was researching this book earlier this summer, my eye was caught by one funeral monument in particular, which reveals a great deal about the values of the people who commissioned it. You can see the version as it is printed in John Le Neve’s book (fig. 1), and as it can still be found on the wall of St. Peter’s Church, Broughton, Staffordshire (fig. 2). This elaborate monument by the prominent London mason, Edward Stanton, commemorates Spencer Broughton, who died on 1st February 1703 (the date is given as 1702 on the monument because at this time the new year was often reckoned from Lady Day, 25th March, rather than 1st January).

The memorial tells us that Spencer Broughton had two careers: first of all, he rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the army of King William III, serving in Ireland, Flanders, and the Caribbean; subsequently, he was appointed Governor of Cabo Corso Castle by the Royal African Company. Cabo Corso Castle, also known as Cape Coast Castle, is in modern day Ghana. It was one of the primary strongholds of the Royal African Company, which was formed during the reign of King Charles II to trade along the coast of west Africa. This company bought not only gold and ivory, but also people, who were forced into slavery, held prisoner at forts like Cabo Corso Castle, and trafficked across the Atlantic ocean to work on British plantations in the Americas. Spencer Broughton, then, was part of a trade that led to the untimely and brutal deaths of hundreds of thousands of African people over the course of the eighteenth century.

I first came across Spencer Broughton’s monument two weeks after a statue of the slave trader, Edward Colston, had been toppled in Bristol in protest at ongoing racial injustice, and a week after Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, announced a review of monuments with connections to the slave trade in English cathedrals. Of course, monuments to people who were involved in human trafficking exist in churches and cathedrals all over Britain and beyond. Few of them, however, celebrate their subjects’ connections to slavery quite as explicitly as Spencer Broughton’s does. And yet to a modern-day reader, who perhaps has never heard of Cabo Corso Castle or the Royal African Company, those connections are not as immediately obvious as they would have been to Broughton’s contemporaries. I wondered whether the priest or the parishioners at Broughton St. Peter were aware of the nature of Spencer Broughton’s career. I decided that I ought to write to Rev. Sara Humphries, curate at St. Peter’s, to find out.

Sara wrote back immediately to tell me that she was deeply shocked but also very glad to learn more about this monument. Now, we are working together to tell the modern-day parishioners of Broughton St. Peter about the monument and its significance. Using images that Sara kindly sent me, I have written an article for the Broughton Parish Magazine about Spencer Broughton and his involvement in the slave trade. Text from this article will also be included on a notice near Spencer Broughton’s monument, which will give visitors to the church context for this memorial. As Sara put it in a message to me, ‘the fact that there is a memorial to a slave trader in a small, remote church, right in the heart of rural England, just shows how widespread this insidious trade was.’

As a white British person and as someone whose academic research focuses on the eighteenth-century, I have a particular responsibility to acknowledge and respond to the long legacies of colonialism and slavery. I was horrified and saddened to see the glorification of human trafficking on Spencer Broughton’s monument, but not surprised by it. Monuments like this offer a tangible reminder that our society today is a product of long-standing inequalities and injustices. I firmly believe that the more we learn and understand about our past, through monuments like Spencer Broughton’s as well as modern-day antiracist writing and activism, the more we can do to fight against racism and other legacies of slavery in our own time.