“The Curious Case of the Contagious Violence in Kerala”

– By Joe Varghese

This work was first presented as a flash talk at the Violence, Health, and the Health Humanities Workshop on 18th June 2025.

Recent violent crimes in Kerala (a state in India) have led society to try to answer the question, “Why has violence committed by unsuspecting ordinary people increased over the last few years?” It is important to consider how the glorification of violence and gore in mainstream media, especially in the movies, may be making the public more desensitised to brutal violence.

In an article on Mint, Arshdeep Kaur talks about how: “Indian cinema has seen the rise of gore in films, beginning with Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Animal in 2023.”[i] He also notes:

After the initial screenings […] viewers said Marco had ‘much more blood and gore’ than even gorefests like Animal, Kill, or the KGF franchise.

So much so that a Manorama report quoted a viewer as saying, ‘The woman who sat next to me threw up on my shirt as she couldn’t bear the violent scenes on screen.’[ii]

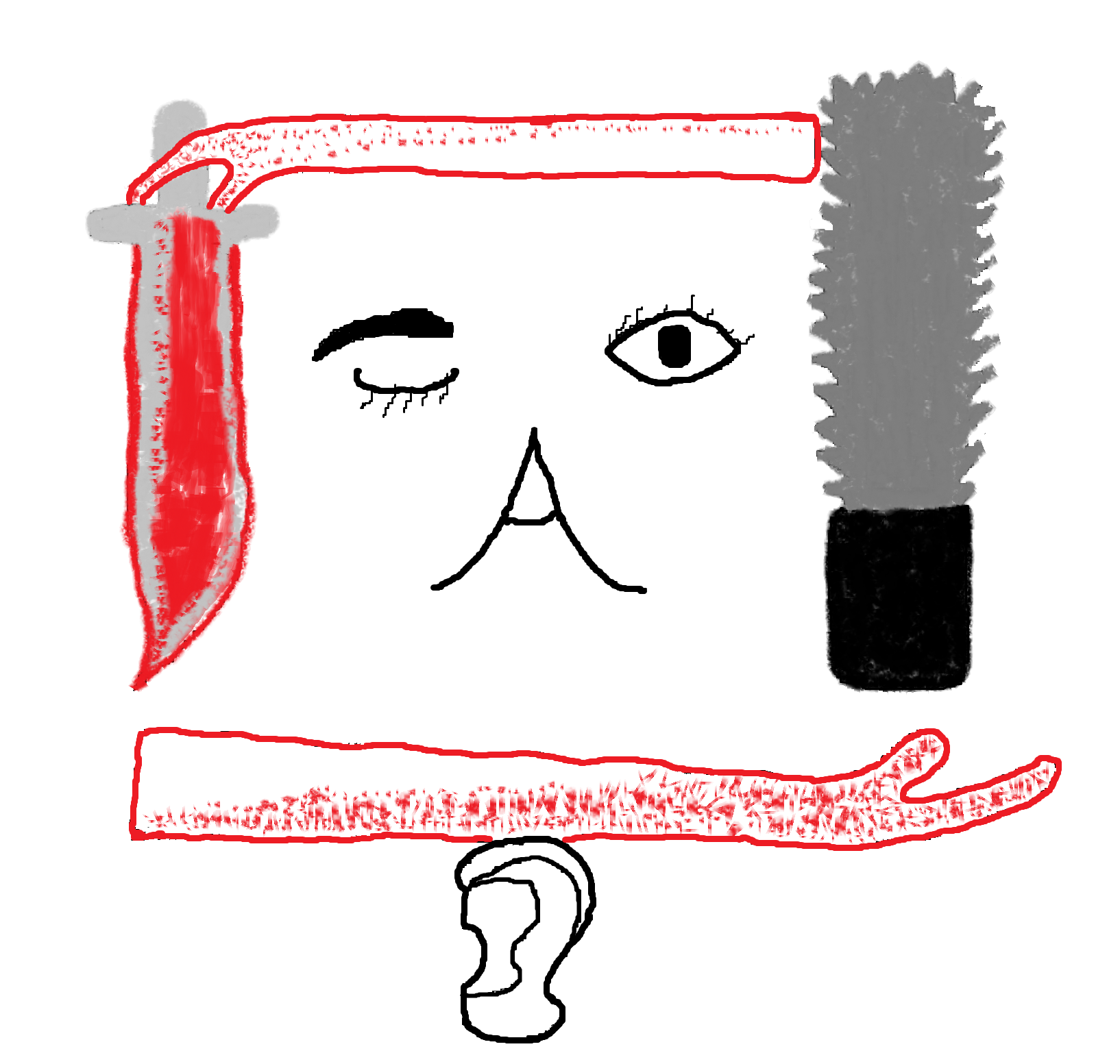

Traditionally, Malayalam films did not portray violence on a large scale. The Malayalam movie Marco[iii] changed that in 2024. The movie portrays extreme violence, including the killing of a blind man by throwing him into acid, chopping hands, biting the ear of a character, smashing a child’s head with a gas cylinder, forcefully taking the foetus out of a pregnant woman, ripping the heart out of an antagonist, and cutting the head off another. The movie’s plot is based on revenge, which begins with the murder of the blind Vincent. This murder is where the contagion begins, and then we see it passed to the protagonist Marco, who goes on a killing spree that spreads violence to everyone, which even causes the death of the innocent, and behaves like a disease that shows no partiality between those who are good and bad. Violence brings death. Here, violence becomes the main character, sidelining the actual protagonist of the movie. The commercial success of the movie was celebrated with the hashtag that the movie created box office records, even after being certified as an “A” movie that is only meant for adult audiences. The violence portrayed in the movie became a major selling point. Reviewers were raving about how it pushed the limits of violence shown on screen in India. The way the public, reviewers, and the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) reacted to the extreme violence in the movie is what makes it different from other violent Indian movies released before this movie.

But the real question is, why is violence celebrated in the first place? In the article on Deccan Herald, Arjun Raghunath talks about how: “The brutal killing of five family members by a youth in Thiruvananthapuram has triggered debates on the influence of violence-packed films on the youths.”[iv] He also explains how: “Senior psychiatrist Dr Arun B Nair said that the increasing instances of youngsters violently reacting to silly issues could be the outcome of influence of visual media, like cinemas, […] among various other factors.”[v]

In the article on BMJ Blogs, Sophie Franklin asks: “To what extent do police officers, social workers, public health officers, and teachers view violence as a contagious disease? And what is the impact of such a perspective?”[vi]

These violent movies are contagious, not just in terms of violence. In the case of the majority of the viewers/public, the possibility of these movies as something that desensitizes the viewers when it comes to blood and brutal murders, and disturbs the minds of the audience, should be considered. However, at the same time, these movies could have a much stronger impact on some individuals who are more susceptible to their influence. So, from a health humanities perspective, analysing this illness narrative, co-authored by authorities (who handled the situation), media, and the public, is crucial because this possibility of desensitisation and influence affects the overall well-being of both the individual who might be easily influenced by such visuals and puts the others around the individual at risk.

The measures taken by the CBFC can be compared to how authorities would handle a disease outbreak or another public health issue. Since the movie is seen as a disease that spreads contagious violence, and since it was already released in theatres and on the OTT Platform, we could see the CBFC trying to stop the further spread of the influence when they decided to stop the TV release. In an article on MensXP, Gaurang Chauhan talks about how: “The […] (CBFC) has blocked the TV premier of the film and has additionally sought a ban on its OTT screening.”[vii] So, not releasing it on TV would prevent it from being seen by a wider general audience, especially children. Some contagious diseases threaten different age groups, and some don’t affect a particular age group that much when compared to another. Censor boards are supposed to take preventive measures to handle such content. So, here, the ‘contagious’ movie is not allowed to exist in a space that is easily accessible to children. The attempt to ban OTT screening could be seen as a way of treating an already existing source to prevent possible further spreading of the disease, which is already ‘isolated’ when we consider the parental control in devices and other age filters in such platforms. The clips from the movie that are available on YouTube and other social media platforms end up being the weaker variants of the same contagious disease. Like many contagious diseases, what about those who are already exposed to the ‘contagious disease’ but haven’t shown any signs yet? Some diseases have longer incubation periods compared to others. But when it comes to violence, the extreme cases are the ones that are always reported in the media, which sometimes could be the first time the symptom was observable.

In the article in Deccan Chronicle, BVS Prakash explains how: “Producer […] has admitted that Marco, […] was intentionally marketed as a violent film but maintained that it complied with all regulatory guidelines.”[viii] He also talks about how: “He further stressed the importance of distinguishing cinema from real life. ‘Violence has always been part of cinema, but as a responsible citizen, I will no longer promote it,’ he added.”[ix] He also describes how: “Meanwhile, the Film Employees Federation of Kerala (FEFKA) has dismissed claims that films incite violence, calling them a misinterpretation of reality.”[x] Here, we see a reversal of the catharsis process, which is complex for the producer trying to find a balance, where the audience’s reaction to the art creates a cathartic effect on the creator.

In an article in The Print, Triya Gulati talks about how:

Singh recounted how a particular scene, where his character cuts the umbilical cord on a pregnant woman, deeply disturbed him.

‘That scene haunted me. I couldn’t sleep properly; the flashes would keep me awake,’ he said.[xi]

In the article in The Week, Sajin Shrijith notes: “Asked if he found any of the violent scenes particularly upsetting, Kabir cites the scene with the pregnant lady. ‘It was challenging and disturbing to me because my wife was pregnant at the time,’ he says.”[xii] Here, the ‘reel’ violence created during the filming process is contagious and is passed on to the actor in real life. So, if the actor felt disturbed while playing the violent character, it is important to consider how it might be disturbing for the viewers.

The whole ‘illness narrative’ of these ‘violent movies and their influence as the disease’ exists as something that is co-authored by authorities, media, and the public. Here, we observe opposing perspectives when comparing the general view on the movie’s influence, as expressed by the public, authorities, media, and individuals from the film industry. So, based on the perspective of each individual, this ‘curious case of violence’ can be seen as a real issue if the individual accepts the possibility of influence, which gives it the traits of a disease. When the possibility of influence is rejected, it could be turned into a hoax by those who see it from a ‘reel doesn’t influence the real’ perspective.

In an article in The Week, Sajin Shrijith talks about how:

But Marco has become a success with its intended target audience that gets their kick from the John Wick films, […] to Sisu (2022). These are the ones who can stomach extreme violence and horror, the ones who prefer action movies to be as bloody as they can get and the ones who seek the most essential ingredient in any revenge film―catharsis―which Marco delivers. The film’s success is a possible indication of the audience’s evolved tastes post-pandemic.[xiii]

He also explains how: “As for the folks arguing for a ban on such films, they have the option to stay home and watch something else.”[xiv] This shows a different perspective and gives a voice to people who enjoy such violent movies. From a health humanities perspective, the ability to choose is crucial because it also shows how individuals have some control over their choice when it comes to being exposed to contagious violence in these violent movies that might put their overall well-being at risk. This choice can be compared to the decisions individuals make to protect themselves from other contagious diseases.

In the article on the UNESCO website, Mame Omar Diop, Satya Bhushan, and Varada Mohan Nikalje explain how: “Globally, youth must be empowered to be resilient to violence, and to become citizens of the world. […] Global Citizenship Education (GCED) fosters these values.”[xv] They also discuss how: “In Gandhi’s thought, Ahimsa precludes not only the act of inflicting a physical injury, but also mental states like evil thoughts and hatred, […] Ahimsa.”[xvi] So, ‘Ahimsa,’ which gave peace to many minds and which is deeply rooted in Indian culture, seems to be the tonic that is needed to deal with the increase in violence in Kerala, regardless of whether everyone believes in movies influencing this rise in violence.

Joe Varghese is pursuing his PhD in English Literature at the University of Reading. His project is a critical memoir and study of chronic illness. Joe is interested in creative writing, theatre, and chronic illnesses that do not get the attention they deserve. He wants to spread awareness about such conditions to create a better environment for recovery.

Notes:

[i] Arshdeep Kaur, ‘Animal, Kill Dethroned as India’s Most Violent Film; THIS Gore Movie Has Made Viewers Throw up in Theater | Today News’, Mint, 27 December 2024. [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[ii] Kaur, ‘Animal, Kill Dethroned as India’s Most Violent Film; THIS Gore Movie Has Made Viewers Throw up in Theater | Today News’.

[iii] Marco, dir. by Haneef Adeni (Cubes Entertainments, 2024).

[iv] Arjun Raghunath, ‘From “Pani” to “Marco”: Kerala Debates Impact of Glamourisation of Crimes in Films’, Deccan Herald, 27 February 2025. [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[v] Raghunath, ‘From “Pani” to “Marco”’.

[vi] Sophie Franklin, ‘Public Health and the “Disease” of Violence: A Retrospective’, BMJ Blogs, 27 August 2024. [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[vii] Gaurang Chauhan, ‘CBFC Blocks TV Premiere of India’s Most Violent Film “Marco”; Seeks Ban On OTT Streaming’, MensXP, 5 March 2025. [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[viii] B. V. S. Prakash, ‘Marco Producer to Avoid Promoting Violence in Future Films’, Deccan Chronicle, 6 March 2025. [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[ix] Prakash, ‘Marco Producer to Avoid Promoting Violence in Future Films’.

[x] Prakash, ‘Marco Producer to Avoid Promoting Violence in Future Films’.

[xi] Triya Gulati, ‘That Umbilical Cord Scene Gave Me Sleepless Nights: Marco’s Kabir Duhan Singh’, The Print, 2 January 2025. [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[xii] Sajin Shrijith, ‘That One Scene Disturbed Me as My Wife Was Pregnant at the Time: “Marco” Villain Kabir Duhan Singh’, The Week, 13 February 2025. [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[xiii] Sajin Shrijith, ‘From Kill to Marco… the Emergence, and Appeal, of Hyper-Violence in Indian Cinema’, The Week, 26 January 2025. [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[xiv] Shrijith, ‘From Kill to Marco… the Emergence, and Appeal, of Hyper-Violence in Indian Cinema’.

[xv] Mame Omar Diop, Satya Bhushan, and Varada Mohan Nikalje, ‘Ahmisa (Non-Violence), Gandhi and Global Citizenship Education (GCED)’, UNESCO, 20 April 2023 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

[xvi] Diop, Bhushan, and Nikalje, ‘Ahmisa (Non-Violence), Gandhi and Global Citizenship Education (GCED)’.

Bibliography:

Adeni, Haneef, dir. 2024. Marco (India)

Chauhan, Gaurang, ‘CBFC Blocks TV Premiere of India’s Most Violent Film “Marco”; Seeks Ban On OTT Streaming’, MensXP, 5 March 2025 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

Diop, Mame Omar, Satya Bhushan, and Varada Mohan Nikalje, ‘Ahmisa (Non-Violence), Gandhi and Global Citizenship Education (GCED)’, UNESCO, 20 April 2023 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

Franklin, Sophie, ‘Public Health and the “Disease” of Violence: A Retrospective’, BMJ Blogs, 27 August 2024 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

Gulati, Triya, ‘That Umbilical Cord Scene Gave Me Sleepless Nights: Marco’s Kabir Duhan Singh’, The Print, 2 January 2025 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

Kaur, Arshdeep, ‘Animal, Kill Dethroned as India’s Most Violent Film; THIS Gore Movie Has Made Viewers Throw up in Theater | Today News’, Mint, 27 December 2024 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

Prakash, B. V. S., ‘Marco Producer to Avoid Promoting Violence in Future Films’, Deccan Chronicle, 6 March 2025 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

Raghunath, Arjun, ‘From “Pani” to “Marco”: Kerala Debates Impact of Glamourisation of Crimes in Films’, Deccan Herald, 27 February 2025 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

Shrijith, Sajin, ‘From Kill to Marco… the Emergence, and Appeal, of Hyper-Violence in Indian Cinema’, The Week, 26 January 2025 [Accessed 20 March 2025].

——, ‘That One Scene Disturbed Me as My Wife Was Pregnant at the Time: “Marco” Villain Kabir Duhan Singh’, The Week, 13 February 2025 [Accessed 20 March 2025].