In this extraordinary academic year, the Centre for Health Humanities aims to encourage and support research which seeks to address historical, modern, and global questions relating to who we are, how we define health and the atypical, and how we envisage strategies for coping and recovery. The Centre is thus supporting three research fellowships, held by colleagues within the University, who are aiming to use the arts and humanities as a means to address the impact, the challenges, and long-term effects of health, sickness, and 'difference'.

Monstrous Bodies in Ancient Culture and Contemporary Art

Dr Emma Aston (Classics)

Dr Emma Aston (Department of Classics) holds a CHH Fellowship in spring 2021. During this period she will work with Prof. Andrew Mangham (Department of English Literature) and contemporary painter Paul Reid to design a project considering the modern artistic legacy of Greek mythology.

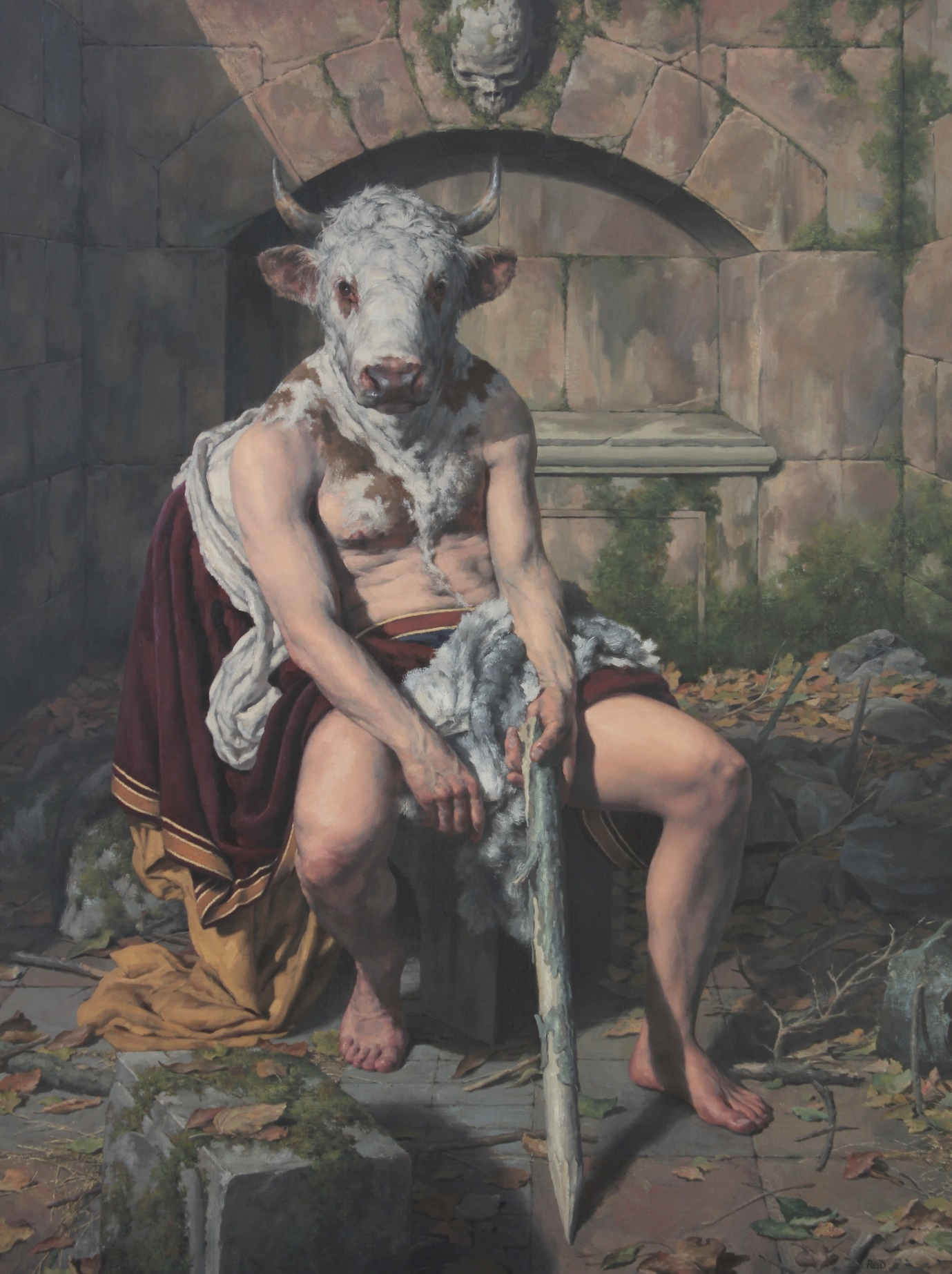

Why do so many mythological monsters combine human and animal elements in hybrid form? Why do hybrids have such enduring power in modern popular and visual culture? What do monsters tell us about a society’s attitudes to normality and abnormality and to human and non-human identity? Such questions lie at the heart of the Monstrous Bodies project, whose planned culmination is an event bringing together academics and non-academics and focusing on a selection of Paul Reid’s paintings.

Paul Reid trained at the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, Dundee (1994-1998), and during that period also studied in Madrid and Florence. He has held many exhibitions of his work, especially in Scotland and northern England, to great critical acclaim. Greek mythology is one of his chief inspirations, and his animal-human figures (Minotaurs, Centaurs, Pan and others) challenge the viewer with their disturbing composite bodies and mysterious lives.

'Minotaur’ by Paul Reid, 2020

Oil on Canvas, 75x100cm

(Reproduced by kind permission of the artist)

Health messages by people for people

Dr Matthew Lickiss (Typography & Graphic Communication)

COVID-19 has led to an explosion of communication about the pandemic in the UK – not just from the government and national agencies, but from ordinary people in all walks of life.

Health messages by people for people investigates how people use verbal and graphic language to document, communicate about, and respond to the pandemic and the related medical interventions (such as vaccines). Such communications have direct consequences on people’s lives, behaviours, health, economic resilience, and social relationships; and their analysis can provide insight strengthen professional communications.

Fevered brows: tracking changing attitudes to fairness in gendered healthcare roles across two pandemics

Professor Jacqui Turner (History) and Dr Charlotte Newey (Philosophy)

In the 1918-1920 pandemic, female nurses became the reassuring face of medicine, in the light of minimal medical interventions from a highly masculine medical profession. Today, caring roles, in the NHS and beyond, typically fall to women. Women make up 70% of the global health workforce, undertaking much of the most dangerous and least glamorous work in healthcare. In 1918, providing nursing care for flu patients was reported as a source of immense pride and satisfaction. In 2020, some nurses express exasperation at the physical and emotional demands of caring for COVID-19 patients, lack of adequate PPE and behaviours of the general public, such as failing to observe safety measures against the spread of the disease.

Our project is an exciting new collaboration between History and Philosophy in which we will identify past attitudes, representations and burdens of caring for flu patients. Next, using oral testimonies from current carers, we seek a deeper understanding of current attitudes to the gendered caring roles in the present pandemic. How have expectations and attitudes changed? In understanding changing attitudes to gendered caring roles across time, what do we learn about the concept of fairness?

We will investigate whether the gendered nature of caring roles is unfair because of the increased risks compared with the lower rewards that people (typically women) in caring roles receive. Is NHS England’s commitment to fairness as a guiding principle met in today’s healthcare settings?