As atmospheric CO₂ rises, ecosystems around the world respond in complex and sometimes surprising ways. One such response involves the balance between two major types of plants on Earth: C3 plants (left), which include trees and most temperate grasses, and C4 plants (right), which dominate many tropical grasslands and savannas and include important crops like maize and sugarcane.

Understanding how the global abundance of C3 and C4 vegetation is changing and what this means for the carbon cycle, is essential for interpreting long-term trends in the atmosphere, including the isotopic “signature” of CO₂.

A new study led by Alienor Lavergne with LEMONTREE team members, published in Communications Earth & Environment, uses a global optimality-based model of C3 and C4 plant distribution combined with a simple carbon-cycle model to investigate how the changing balance between these plant types has contributed to the observed trend in atmospheric carbon isotopes over the past four decades. The work builds on long-standing uncertainties around why atmospheric carbon isotopes (δ¹³CO₂) are declining more slowly than expected, a discrepancy linked to the well-known Suess effect.

A global decline in C4 vegetation despite growing C4 croplands

Lavergne’s model suggests that the fraction of C4 vegetation globally declined from about 16% to 12% between 1982 and 2016.

This may seem counter-intuitive, given that C4 crops have expanded over the same period. But rising CO₂ gives a stronger competitive advantage to C3 plants, which benefit more from CO₂ fertilisation than C4 species. As a result, natural C4 grasslands and savannas appear to be losing relative ground.

The new model shows strong agreement with observed soil carbon isotopes—one of the best indicators of local C3/C4 vegetation balance—and performs better than previous global maps in key regions like Africa and Australia.

What does this shift mean for global photosynthesis?

The reduced dominance of C4 plants, combined with rising CO₂, results in a substantial increase in global plant productivity.

The study estimates:

- Global gross primary production (GPP) increased by ~16.5 ± 1.8 PgC from 1982–2016

- This is consistent with other reconstructions based on remote sensing and ice-core proxies

- The largest increases occur in regions where C3 plants thrive under elevated CO₂, including tropical and European forests

This reinforces a broader picture: despite widespread ecosystem stresses, global photosynthesis has increased over recent decades, largely because of CO₂ fertilisation.

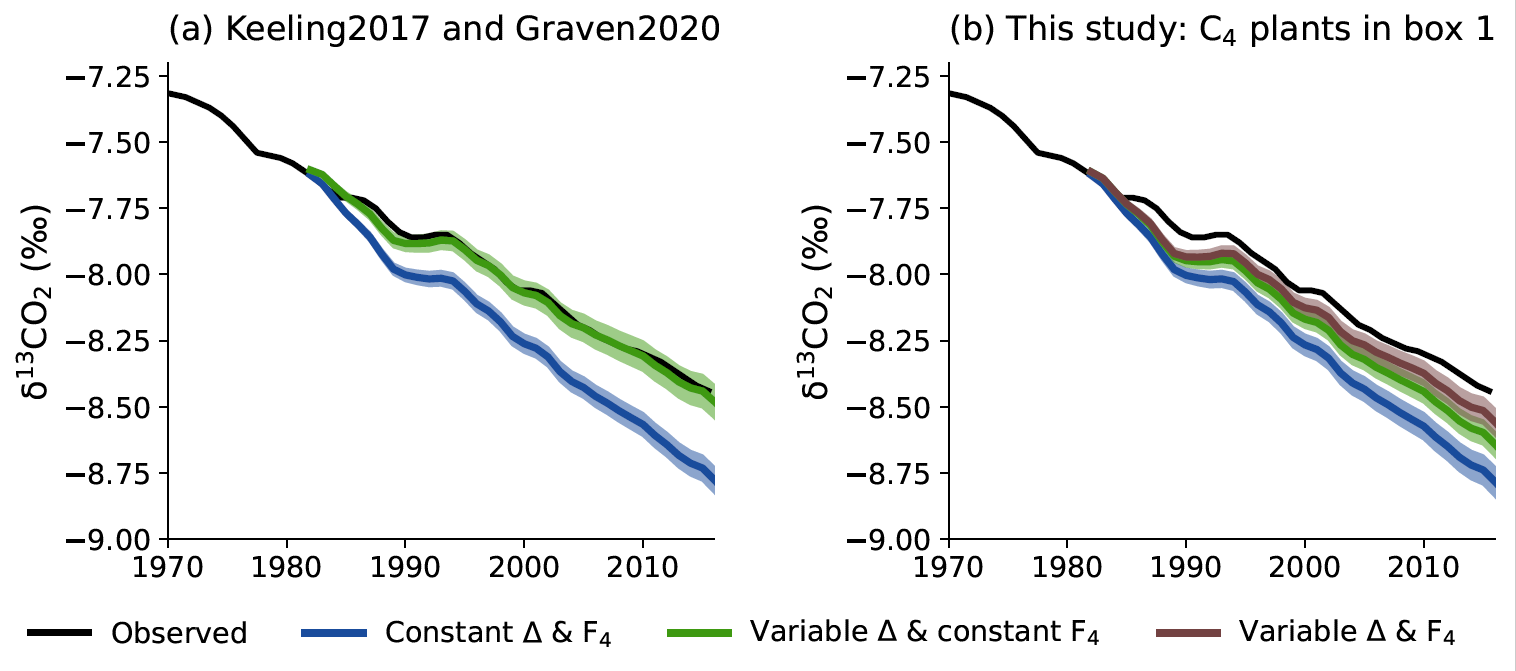

How does this affect atmospheric carbon isotopes?

C3 and C4 plants have different carbon isotope “fingerprints.” C3 plants discriminate more strongly against the heavy carbon isotope (¹³C), meaning changes in their relative abundance can alter the isotopic composition of atmospheric CO₂ (δ¹³CO₂).

This study found:

- If C3/C4 distributions were fixed, Δ¹³C (land carbon isotope discrimination) should increase only slightly with rising CO₂

- But accounting for the observed decline in C4 plants increases global Δ¹³C threefold

- This shift slightly reduces the mismatch between modelled and observed δ¹³CO₂ trends

However, and crucially, the changes in plant abundance can only explain some of the discrepancy.

Even after accounting for changes in C3/C4 coverage and their isotope discrimination, the observed slowdown in the Suess effect remains largely unexplained with the difference between modelled and observed δ¹³CO₂ is reduced but not eliminated

This indicates that other, still unquantified processes, such as soil respiration, post-photosynthetic fractionation or ocean–atmosphere carbon exchange must also be influencing the global carbon isotope budget.

Why does this matter?

Carbon isotopes help scientists understand how much CO₂ is being absorbed by the land and ocean, and how fast. If the expected isotopic response doesn’t match the atmospheric record, it raises questions about how carbon moves through ecosystems and how soils store and release carbon. By showing that changes in C3/C4 vegetation cannot fully explain the slower-than-expected isotopic decline, the study highlights gaps in our understanding of how carbon is processed by the biosphere—a critical issue for predicting future climate-carbon feedbacks.

Conclusion

This study provides the clearest evidence yet that recent global declines in C4 plants have only a minor effect on atmospheric carbon isotope trends. While shifting plant distributions do alter global photosynthesis and isotope discrimination, they cannot explain the slower-than-expected decline in δ¹³CO₂.

Instead, the results point to missing processes in global carbon cycle models, likely involving soils, plant physiology or ocean-atmosphere exchanges that must be better understood to accurately track Earth’s carbon balance under rising CO₂.

You can read the full paper here:

Lavergne, A., Harrison, S.P., Atsawawaranunt, K., Dong, N. & Prentice, I.C. (2026). Minimal impact of recent decline in C4 vegetation abundance on atmospheric carbon isotope composition. Communications Earth and Environment. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03102-6

Alienor is a previous member of Colin Prentice’s team at Imperial College London and has collaborated with the LEMONTREE team for this paper.