Wildfires are already transforming ecosystems and societies worldwide. From record-breaking boreal fires to devastating events at the wildland–urban interface, recent years have heightened concern that fire activity will continue to intensify as the climate warms. Yet satellite observations show a contrasting global signal: total burned area has declined over recent decades, particularly in tropical savannas and grasslands, largely driven by human land-use change.

A new Nature Communications paper led by LEMONTREE’s Olivia Haas with Iain Colin Prentice and Sandy Harrison explores how these apparently conflicting signals might evolve over the coming century and why focusing on burned area alone risks missing critical changes in wildfire behaviour.

Rather than asking how much land will burn, the study asks a broader question: how sensitive are different aspects of wildfire regimes to changes in climate, CO₂, vegetation and human activity?

Moving beyond a single fire metric

Most global assessments of future wildfire risk rely on physical fire danger indices, which consistently increase under climate change. While informative, these indices do not account for how vegetation, atmospheric CO₂ or human activity may amplify, or dampen, fire responses.

This study takes a different approach, using empirical global models to simulate three key properties of wildfire regimes:

- Burnt area

- Fire size

- Fire intensity

The models are driven by climate variables, vegetation productivity and structure, and socio-economic factors such as population density, cropland and road networks. Crucially, vegetation inputs account for the physiological effects of CO₂, allowing climate and CO₂ influences on fire to be examined separately.

Disentangling drivers with sensitivity experiments

A key strength of the analysis lies in its experimental design. To understand why fire regimes change rather than simply how they change, a suite of sensitivity experiments were used in which climate, CO₂, vegetation and human drivers were allowed to vary independently or in combination.

These experiments build directly on the methodological framework developed in Haas et al. (2023), which was designed to disaggregate the tightly coupled historical relationship between climate and atmospheric CO₂. By breaking this correlation, the study can isolate the individual and combined effects of different drivers on future wildfire behaviour — something that is difficult to achieve in many modelling approaches.

Rather than producing a single forecast, this framework reveals how sensitive global wildfire regimes are to different pathways of environmental and socio-economic change.

Two warming pathways

The team examined two contrasting end-of-century scenarios:

- High climate change mitigation (~1.5°C warming)

- Low climate change mitigation (3–4 °C warming)

Both scenarios follow a “middle-of-the-road” socio-economic pathway and were evaluated using multiple global climate models, helping to capture uncertainty in future climate and vegetation responses.

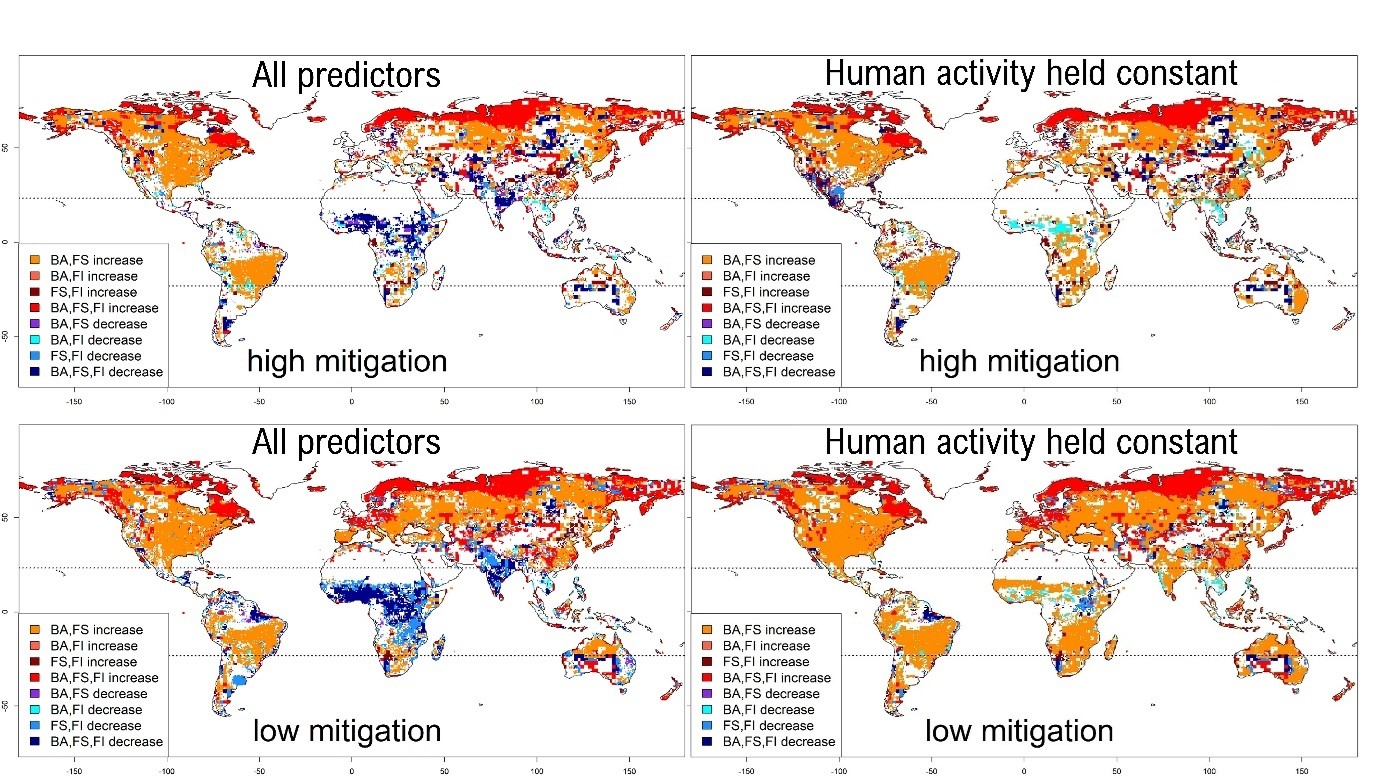

Under high mitigation: The global decline in burned area continues, dominated by reductions across tropical regions linked primarily to increased human activity and landscape fragmentation. However, this global signal conceals important changes elsewhere. Fire probability expands into large parts of the northern extra-tropics, including boreal forests and tundra, where fires have historically been rare. In these regions, fires also become larger and more intense, driven mainly by increasing dryness and atmospheric demand.

Under low mitigation: The balance shifts. Climate and CO₂ effects overwhelm human-driven reductions, leading to substantial increases in burned area across all vegetation types, including the tropics. In both scenarios, northern ecosystems experience the largest increases in fire size and intensity.

What this study does, and does not, aim to do

This is not a prediction of future fire activity. Instead, the purpose is to explore sensitivity: how different components of wildfire regimes respond to changes in their key drivers, and how those responses differ across regions and fire properties. What is surprising is not just where fires will increase or decrease, but how differently burned area, fire size and fire intensity respond to the same changes. Even when the global signal looks reassuring, there are big shifts happening underneath, especially in places that haven’t historically been fire prone.

By using contrasting climate pathways, multiple climate models and targeted sensitivity experiments, the study explicitly addresses uncertainty in future forcing and ecosystem responses. The results highlight that relationships between different fire properties observed today may not hold in the future — and that understanding wildfire risk requires looking beyond a single metric.

Fire regimes on a changing planet

One of the clearest messages from this work is that future wildfire regimes will be redistributed, not simply intensified everywhere. Some regions may see less burning overall but experience profound changes in fire behaviour, while others may face new or expanding fire activity for the first time.

Even under ambitious climate mitigation, the study shows that changes in climate and vegetation can lead to larger and more intense fires in parts of the world, underscoring the complexity of wildfire responses in a warming climate.

By focusing on sensitivity rather than prediction, this analysis provides a framework for understanding why wildfire regimes may change, and why managing fire in the future will require grappling with multiple interacting drivers, rather than relying on past relationships alone.

You can read the full paper here:

Haas, O., Prentice, I.C. & Harrison, S.P. (2026). Wildfires on a changing planet. Nature Communications, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68176-4

You can also read previous blog on Olivia’s research here:

Sept 2024: New Research on the Global Drivers of Wildfire. – Lemontree

June 2024: Modelling Fire in France: From Global to Local – Lemontree

July 2022: Extreme heat in the UK and wildfires: why we should expect it to happen again – Lemontree