Plants face a fundamental coordination problem: how much carbon to invest in water transport tissues to support a given leaf area. Too little sapwood, and water supply limits photosynthesis; too much, and carbon is wasted on unnecessary hydraulic infrastructure. The ratio of sapwood area to leaf area, known as the Huber value (vH), captures this balance at the whole-plant level and sits at the intersection of carbon uptake, water transport and climate.

Despite its importance, global variation in vH has remained difficult to explain mechanistically. Observed patterns clearly reflect climate and hydraulic traits, but until now there has been no general framework linking these patterns to first principles in a way that can be readily applied in vegetation models.

In our new paper published today in New Phytologist, Huiying Xu and colleagues present a simple but powerful explanation grounded in eco-evolutionary optimality (EEO). This study shows that much of the global variation in sapwood–leaf area ratios can be understood as the outcome of plants optimally balancing water supply and water demand under different environmental conditions.

The ratio of sapwood to leaf area has never been more critical for tree survival during drought. By uncovering its variation, we offer a mechanistic framework to help improve representation of carbon allocation in next generation of vegetation models.

Huiying Xu – Lead Author

An optimality perspective on plant hydraulic allocation

The starting point of the study is the idea that under optimal conditions, the maximum rate at which water can be transported through the xylem should match the maximum water loss associated with photosynthesis. This principle implies that hydraulic and photosynthetic traits must be tightly coordinated.

The key advance here is to embed this idea within a modern EEO framework. Rather than treating vH as a fixed trait or tuning it empirically, we have derived an expression for optimal vH by explicitly linking:

- atmospheric demand for water (via vapour pressure deficit),

- photosynthetic capacity (driven by light and temperature),

- and hydraulic efficiency (via sapwood-specific conductivity).

Crucially, photosynthetic traits such as stomatal behaviour and carboxylation capacity are not prescribed but predicted using existing optimality models that assume plants minimise the combined costs of carbon gain and water loss. This allows vH to be expressed directly as a function of climate and hydraulic traits.

Testing the theory against global data

To test their predictions, the authors compiled two extensive global datasets. One captures species-averaged hydraulic traits across broad climatic gradients, while the other links individual-level measurements to local climate conditions. Together, these datasets allow the theory to be evaluated both across evolutionary timescales and along contemporary environmental gradients.

Rather than focusing on complex equations, the key question is simple: does an optimality-based model reproduce observed global patterns of sapwood–leaf area allocation?

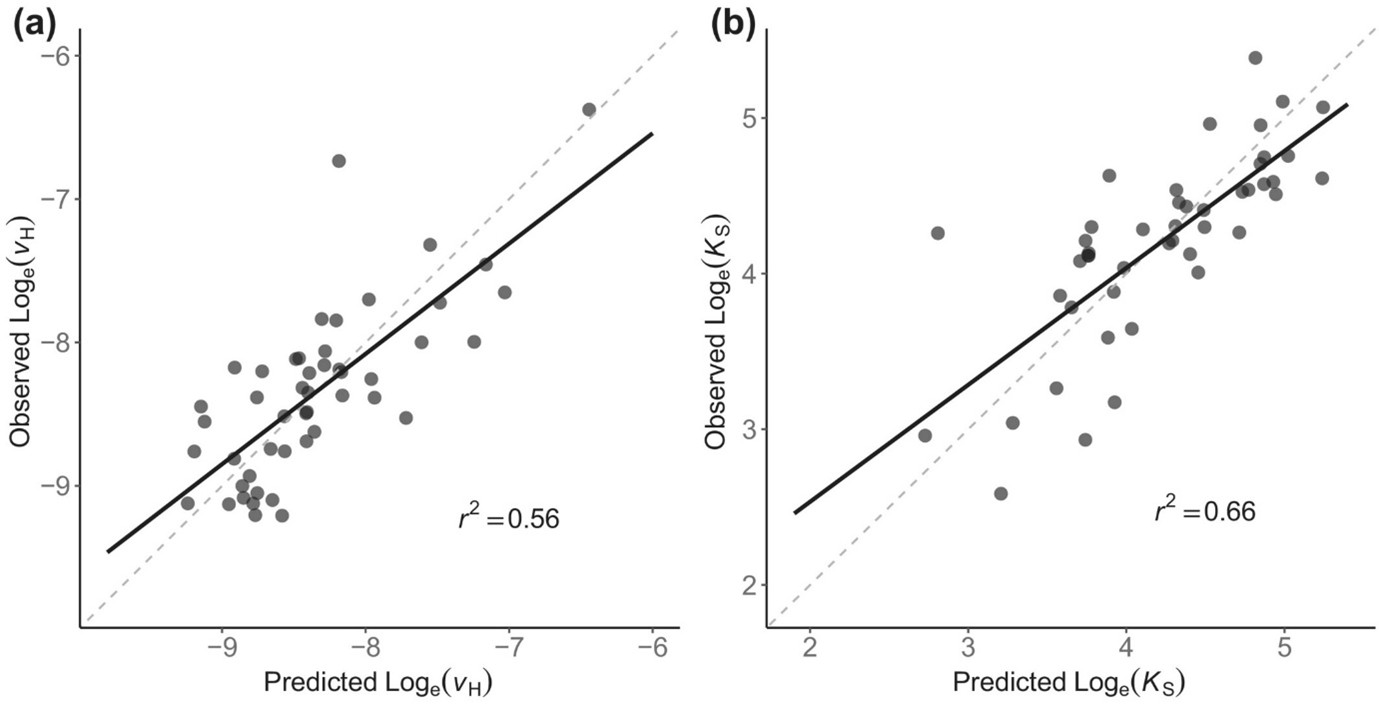

The answer is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows a strong correspondence between predicted and observed vH values across climate types. Points cluster around the 1:1 line, indicating that the theory captures more than half of the observed global variation in sapwood–leaf area ratios using climate variables and a single fitted intercept. In fact, we show that our eco-evolutionary optimality-based model explains nearly 60% of global vH variation in response to light, vapour pressure deficit, temperature and sapwood conductivity.

This level of agreement is encouraging, given the simplicity of the framework. Rather than relying on plant functional types or biome-specific parameterisations, the model explains trait variation as an emergent outcome of optimal allocation under environmental constraints.

Climate controls on sapwood–leaf area ratios

The theory predicts — and the data confirm — clear and interpretable climate sensitivities:

- Higher vapour pressure deficit increases vH, reflecting greater investment in sapwood to sustain water supply under dry air conditions.

- Higher irradiance also increases vH, as greater photosynthetic capacity raises transpirational demand.

- Warmer temperatures, by contrast, tend to reduce vH, largely because warmer conditions enhance hydraulic efficiency and reduce the sapwood area needed to support a given leaf area.

These opposing temperature and atmospheric dryness effects are particularly important in the context of climate change. While both temperature and vapour pressure deficit are increasing globally, their contrasting influences on vH mean that plant hydraulic responses cannot be inferred from temperature trends alone.

Across all analyses, sapwood-specific hydraulic conductivity emerges as the dominant control on vH, consistent with long-recognised trade-offs between conducting efficiency and conducting area. Species with more efficient xylem can support a given leaf area with less sapwood investment, while species with lower conductivity compensate by increasing sapwood area.

Trait coordination across species and strategies

The study also sheds light on differences among plant strategies. Evergreen and deciduous species differ in their typical combinations of hydraulic efficiency and sapwood investment, but both groups conform to the same underlying optimality relationships. This suggests that contrasting strategies reflect different positions along a shared trade-off surface, rather than fundamentally different rules.

Importantly, the tight coordination between vH and hydraulic conductivity across species implies that these traits have evolved together over long timescales in response to climate. At the same time, evidence from individual-level data indicates that vH can adjust (e.g., through leaf shedding or growth) on shorter timescales in response to environmental stress, although full optimisation may take years or decades.

Why this matters for models and climate change

Most current vegetation models treat the Huber value as fixed, ignoring its observed variability and sensitivity to climate. This study provides a mechanistic, theory-based alternative, showing how whole-plant hydraulic traits can be predicted from environmental conditions and trait coordination alone.

By providing a parsimonious, theory-based representation of sapwood allocation, this work opens the door to more realistic modelling of plant water use, carbon uptake and drought vulnerability. Because the framework links hydraulic allocation directly to environmental drivers, it also offers a potential early-warning indicator of hydraulic stress when observed vH deviates strongly from its predicted optimal value.

Ultimately, the study shows that the diversity of plant hydraulic strategies we observe worldwide is not arbitrary. Instead, it reflects a simple organising principle: plants balance water transport tissue and leaves in ways that maximise performance under the constraints imposed by climate.

You can read the paper here:

Xu, H., Wang, H., Prentice, I.C., Harrison, S.P., Rowland, L., Mencuccini, M., Sanchez- Martinez, P., He, P., Wright, I.J., Sitch, S., Li, M. & Ye, Q. (2025). Global variation in the ratio of sapwood to leaf area explained by optimality principles. New Phytologist, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.70916