In a warming world, climate extremes are no longer isolated events. Increasingly, heatwaves, droughts, and floods strike in tandem, overwhelming natural ecosystems. One underappreciated driver of these compound extremes is a large-scale atmospheric pattern known as Rossby Wave-7 (RW7), a repeating, meandering shape in the jet stream that locks weather systems in place. But what does this mean for the Earth’s biosphere?

Recent research led by LEMONTREE’s Xu Lian has uncovered that RW7 events act as amplifiers of ecological stress. These jet stream configurations increase the frequency and intensity of compound climate extremes, such as simultaneous heat and drought or cold and excessive rainfall. More importantly, ecosystems respond nonlinearly to these events, meaning their productivity doesn’t just decline—it can collapse.

“We found that Rossby waves cause synchronized GPP declines in high-pressure regions. Even more concerning: when hot-dry conditions hit extreme levels, there are non-linear GPP reductions. This is not good news given that today’s hot-dry extremes may become the norm in a warmer and likely drier future.”

— Xu Lian, lead author of the study

Introducing the Amplifying Impact Factor

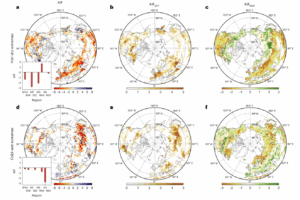

To quantify this hidden stress, scientists developed the Amplifying Impact Factor (AIF)—a new metric that measures how much additional ecosystem damage occurs when RW7 patterns are present. AIF has two components:

- AIFatm: How much RW7 increases the chance of compound extremes.

- AIFland: How ecosystems uniquely respond to those extremes during RW7 events, beyond what we’d expect in normal conditions.

Together, these factors reveal a clear story: RW7 patterns are not just weather anomalies, they are ecological risk multipliers.

The map below shows how RW7 patterns amplify ecosystem damage through both atmospheric anomalies and enhanced vegetation sensitivity—captured by the Amplifying Impact Factor (AIF).

RW7 and the Perils of Heat and Drought

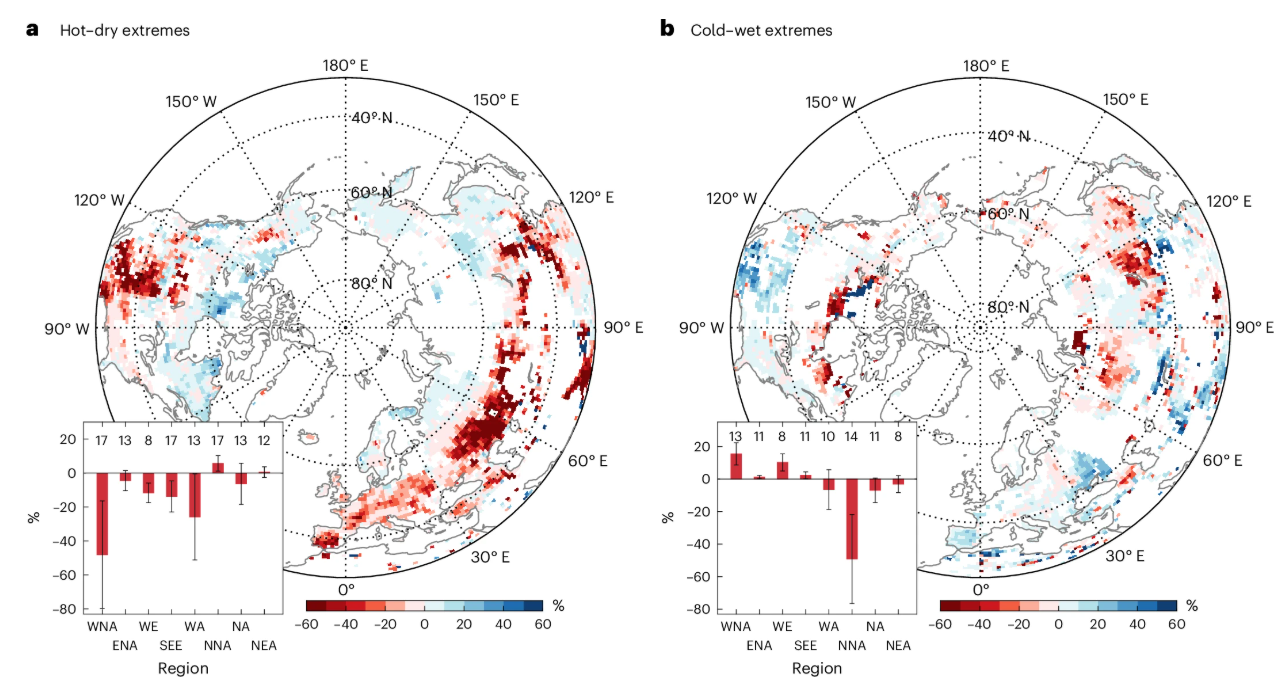

The most striking findings come from hot–dry compound extremes. RW7 events expose large swaths of the Northern Hemisphere to extreme heat and low soil moisture, particularly across Western North America, Western Europe, Western Asia, and South China. In these regions, ecosystems are pushed to their physiological limits.

Trees and plants shut their stomata to conserve water, reducing their ability to absorb CO₂. At the same time, the enzyme RuBisCO, which drives photosynthesis, becomes less effective under thermal stress. The result? A dramatic drop in plant productivity.

These productivity declines are not isolated. Satellite data show widespread losses across the Northern Hemisphere during RW7-driven compound events, as seen below.

Cold–Wet Isn’t Always Better

Interestingly, not all compound extremes involve heat. RW7 events can also trigger cold–wet extremes, which suppress productivity in places like North America, eastern Europe, and northern Canada. These regions experience limited photosynthesis due to colder temperatures and waterlogged soils, sometimes showing even larger losses than during heatwaves. Still, there are rare exceptions: some cold regions like alpine tundra show improved productivity under the right balance of cool temperatures and moisture.

An Indication of the Future?

What makes this all more concerning is how closely RW7-driven events resemble our projected future climate. Under a moderate emissions scenario (SSP2–4.5), climate models forecast warmer and drier conditions by the end of the century, conditions nearly identical to those observed during RW7 events today.

In fact, a large share of weekly temperature and soil moisture anomalies during RW7 events already fall within the expected range of future changes. This makes RW7 patterns a sort of natural laboratory, offering a preview of how ecosystems might behave in the coming decades. Unlike controlled experiments, RW7 events capture the real-world complexity and variability of climate stress.

But Natural Experiments Have Limits

Despite their value, RW7 events can’t tell us everything. They are episodic and rare, so the sample size for extreme events remains small. Plus, real-world conditions involve multiple overlapping stressors (like high radiation paired with drought), making it hard to isolate cause and effect.

Most importantly, these patterns reflect short-term physiological responses. Long-term ecological shifts, such as plant acclimation to warming, are harder to observe in such fleeting episodes. There is growing evidence that plants can adjust their temperature thresholds over time, potentially softening the blow of future heat stress. But these dynamics remain underrepresented in current observations.

A Warning Signal for the Carbon Cycle

RW7 events are not just weather anomalies, they have continental and even global implications. By synchronizing climate stress across vast areas, they can reduce ecosystem productivity on a scale large enough to affect the global carbon budget. As such events become more frequent or severe in a warming world, we may witness regional tipping points, beyond which ecosystems can no longer recover.

This research highlights the importance of integrating atmospheric dynamics into ecological forecasting. Jet stream patterns like RW7 are shaping not just the weather, but the planet’s ability to sequester carbon. As we chart a course through an uncertain climate future, these findings offer a sobering reminder: it’s not just the heat or the drought, the pattern behind them matter too.

You can read the full paper here:

Lian, X., Li, Y., Liu, J., Kornhuber, K. & Gentine, P. (2025). Northern ecosystem productivity reduced by Rossby-wave-driven hot-dry conditions. Nature Geoscience, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01722-3