A new study led by LEMONTREE’s newly minted PhD, Dr Theodore Keeping, uncovers how global climate modes, from El Niño to Atlantic temperature cycles, steer American wildfire patterns today and in a warmer future.

Wildfires in the United States are controlled by the effect of local weather on fuel conditions and vegetation productivity. Possible weather in a given fire season is shaped by predictable global climate patterns—large, slowly shifting modes such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), and temperature swings in the tropical Atlantic. These climate modes in the atmosphere, alter rainfall, heat, vegetation growth, and ultimately, the likelihood that fires ignite and spread.

It has long been suspected that these global modes play a major role in US wildfire risk. But despite tree ring fire scar providing a robust picture of these long-term associations, such studies are limited to small geographic regions. Conversely, the satellite record covers a large area but has a small sample window given the noisiness of wildfire occurrences. It’s has therefore been hard to pin down where and how strongly these modes influence fire.

A new paper in Climate Dynamics, led by Dr Theodore Keeping, changes that.

This research builds directly on the large-ensemble (LE) wildfire occurrence model that Theodore previously developed and published in Frontiers earlier in 2025. That earlier study—summarised in a LEMONTREE blog post here—laid the groundwork by constructing a probabilistic model capable of simulating thousands of years of wildfire activity under different climate conditions. The new study uses this model to explore a different question:

“How do global climate modes shape wildfire variability across the US, and how will that influence change as the planet warms?”

Outline of Methods

To see how climate variability affects wildfires, the team used:

- A probabilistic wildfire occurrence model from the earlier Frontiers paper

- A large climate ensemble of 1600 simulated years from the EC-Earth3 climate model

- Two time slices: a “recent climate” (2000–2009) and a “+2°C world”

- Eleven global climate modes, each representing major patterns of ocean–atmosphere variability

This large-ensemble approach gives us something observations cannot: hundreds of ENSO cycles, hundreds of Indian Ocean Dipole events, and many combinations of modes that might only occur once in a century. That makes it possible to isolate their true influence on wildfire.

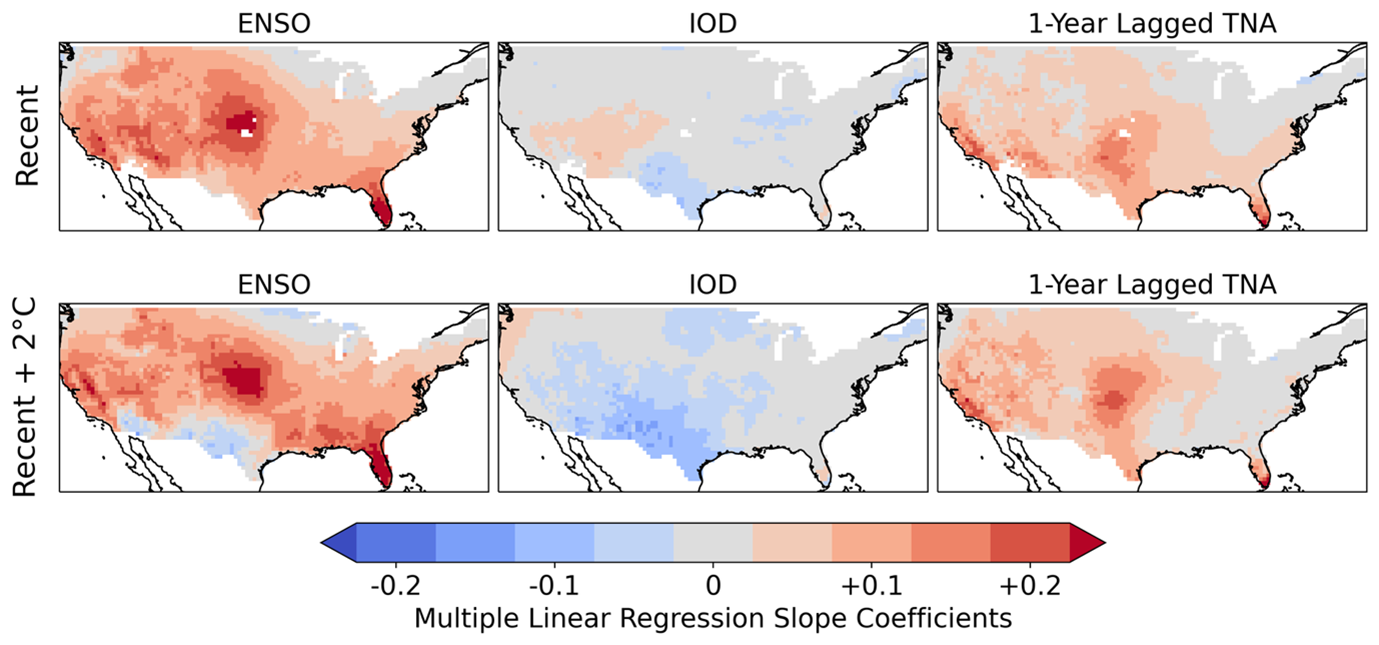

The Big Three: ENSO, IOD and TNA+1

Across the entire United States, three modes stood out as most strongly related to year-to-year wildfire variability:

- ENSO (El Niño / La Niña) – influences wildfire in 91% of the country

- IOD (Indian Ocean Dipole) – influences 90%

- TNA+1 (Tropical North Atlantic SSTs from the previous year) – influences 82%

These modes are reasonably correlated, supporting the notion that ENSO is the dominant control of US wildfire variability, with the IOD and TNA able to strengthen its effect.

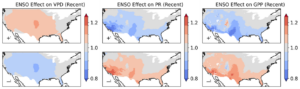

La Niña is the most important driver: La Niña events significantly increase wildfire occurrence across:

- California’s Mediterranean region

- The Southwest

- The Great Plains

- Southern Florida

These effects arise through hotter conditions, higher vapour-pressure deficit (VPD), and reduced precipitation, all of which dry out vegetation and increase ignition likelihood.

One of the most striking results: ENSO is not significantly associated with wildfire occurrence in the northwestern US, despite decades of tree-ring literature suggesting otherwise. ENSO does influence fire size in that region, but not the probability of a small fire occurring, which is what this model tracks.

IOD and TNA+1: Although both modes are correlated with ENSO, the analyses show that TNA+1 retains a strong, independent influence even after accounting for ENSO effects.

The IOD also plays an important role, particularly in the southern US, and becomes more influential under +2°C warming.

Climate modes also shift the timing of the fire season

ENSO doesn’t just change how many fires occur, it also changes when they occur.

La Niña tends to:

- lengthen the fire season in California, the Southwest, the Great Plains and Florida

- push the seasonal peak later in the Southwest

- pull the peak earlier in the Southeast

The IOD and TNA+1 produce similar seasonal shifts in some regions, though with smaller geographic footprints.

This is important for fire agencies, because shifts in timing affect resource allocation, readiness levels, prescribed burning windows and the overlap with lightning season.

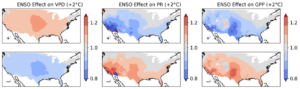

Warming strengthens the power of climate modes

In a world 2°C warmer, climate modes become stronger predictors of wildfire occurrence and the area influenced by several modes increases substantially:

- AMO+1: from 38% → 68% of the US

- PNA: from 16% → 56%

- AO: from 10% → 37%

ENSO, IOD and TNA+1 remain dominant, but the magnitude of their effect increases, particularly in the Great Plains and Western US.

Why the Great Plains are particularly sensitive

Across both climates, the Great Plains emerge as the region where wildfire probability is most sensitive to climate variability. Grasslands rapidly accumulate fuel during wet periods and rapidly dry during warm, dry phases of ENSO and TNA+1, making them extremely responsive to year-to-year climate swings.

With warming, this sensitivity intensifies.

What does this winter have in store?

With early signs pointing toward a La Niña this winter, this work provides timely evidence that such a shift could raise wildfire probabilities across large parts of the US if La Niña persists into next year. Offering both a scientific heads-up and a practical planning tool.