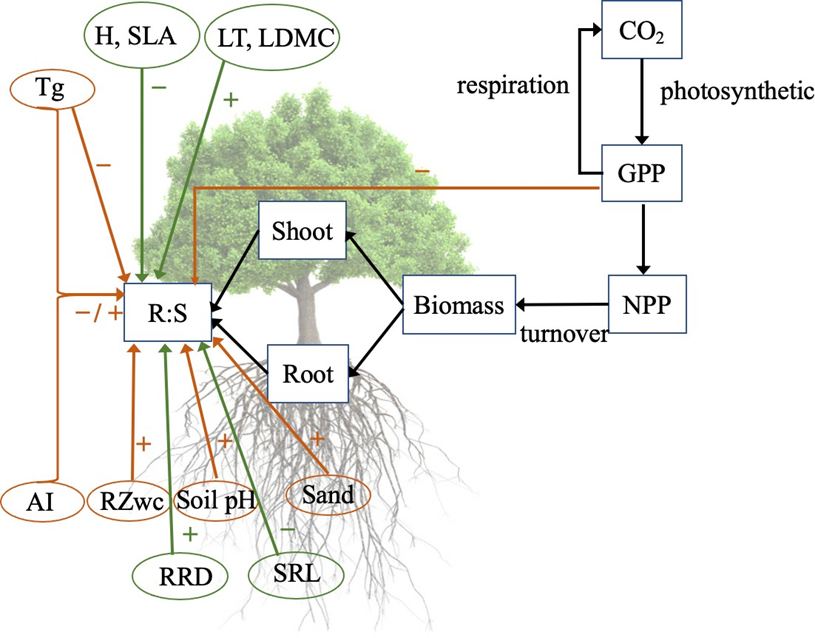

How plants divide their resources between roots and shoots, i.e., the ratio of root to shoot biomass (R:S) is a crucial indicator of how plants adapt to their environments. Root investment supports water and nutrient uptake, while shoot investment allows leaves and stems to capture carbon and light. This allocation strategy has direct implications for the global carbon cycle and climate, because it shapes how vegetation responds to environmental stressors, and how much carbon is stored above versus below ground.

A new study in Global Change Biology by Ruijie Ding and Colin Prentice (Imperial College London), with Rodolfo Nóbrega (Bristol University) takes a global look at the environmental and trait-based factors controlling R:S.

Why root:shoot matters

Plants face a fundamental trade-off: how much carbon to invest in roots versus shoots. More roots mean greater ability to access water and nutrients, but less carbon available for above ground competition for light. More shoots enable rapid carbon assimilation and height growth, but risk insufficient resource uptake from the soil.

From an evolutionary perspective, plants are expected to balance these competing demands in ways that maximise fitness. This idea underpins the eco-evolutionary optimality (EEO) framework, which is central to LEMONTREE research. EEO posits that plants optimise resource allocation given environmental constraints, leading to predictable patterns across ecosystems.

Understanding these patterns is not just an academic exercise. How plants allocate carbon affects ecosystem productivity, resilience to climate stress, and the storage of carbon in biomass and soils, currently all key uncertainties in Earth system models.

A global dataset

The team compiled an extensive dataset of 29,896 observations of R:S, spanning woody and herbaceous species across all climatic regions. This global perspective allowed them to test how R:S relates not only to climate variables such as growth temperature, aridity, and water availability, but also to soil conditions (pH, sand content), ecosystem productivity (GPP, or gross primary production), and plant functional traits such as:

- Height (H) and specific leaf area (SLA) – taller plants often prioritize aboveground growth.

- Leaf thickness (LT) and leaf dry matter content (LDMC) – traits linked to stress tolerance.

- Rooting depth (RRD) – associated with drought avoidance.

- Specific root length (SRL) – traits affecting nutrient and water uptake.

By combining these environmental and trait factors into parsimonious statistical models, the researchers could disentangle the relative influences on biomass allocation.

What the study found

Across all species, R:S values ranged widely—from as low as 0.009 in woody plants to 14.469 in herbaceous plants. Median values reflected this sharp contrast: woody plants averaged around 0.25, while herbaceous plants averaged nearly an order of magnitude higher (4.7).

Despite this variation, consistent patterns emerged:

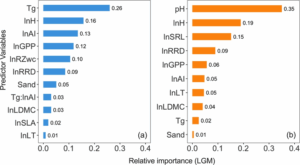

- Woody and herbaceous plants showed broadly similar controls on R:S, though herbaceous plants exhibited stronger trait-driven variability.

- Higher GPP (productivity), higher temperatures, and greater plant height all reduced R:S, pointing to greater allocation above ground when environmental conditions favour growth.

- Soil sand content, rooting depth, and leaf dry matter content increased R:S, reflecting greater belowground investment under stressful or resource-limited conditions.

- Root zone water capacity (RZWC) increased R:S, consistent with the idea that plants build root systems to buffer against seasonal drought.

- Soil pH mattered for herbaceous plants, with higher pH (more alkaline soils) reduced N acquisition costs and the cost of maintaining photosynthetic capacity, leading to greater root allocation.

Interestingly, the influence of temperature was context-dependent. Under moist conditions, higher temperatures reduced R:S, consistent with faster nutrient turnover in warm soils. But under drier conditions, the negative effect of temperature weakened, or even reversed—plants in hotter, drier climates increased root investment to cope with water stress.

In total, the models explained around 13% of variation for woody species and 31% for herbaceous species. While not exhaustive, these are robust signals considering the complexity of plant strategies and the diversity of environments sampled.

Connecting to eco-evolutionary theory

The results provide broad support for predictions derived from EEO theory. In particular:

- R:S allocation declines with increasing GPP, because once leaf demand is met, surplus carbon goes to stems.

- Cold or dry conditions increase R:S, as plants invest in roots to overcome nutrient or water constraints.

- Stress-tolerant traits such as thick leaves, dense tissues, and larger rooting depth increase R:S.

- Resource-acquisitive traits such as tall stature, high SLA, and long fine roots reduce R:S.

These findings align with the concept of EEO where plant carbon allocation reflects optimal responses to the twin demands of photosynthesis and resource acquisition.

Woody vs herbaceous: different strategies

While the broad patterns held for both plant types, some key contrasts stood out.

- Woody plants tended to allocate less to roots, consistent with their long-term structural investment and deeper rooting systems. Traits such as leaf thickness and dry matter content were particularly important in shaping R:S.

- Herbaceous plants, by contrast, showed stronger responses to soil conditions such as pH and SRL. This reflects their strategy of building fine, extensive root networks to capture nutrients efficiently, especially in variable environments.

Shrubs, a smaller subset in the dataset, showed more idiosyncratic patterns, partly because of their uneven geographic distribution. Nonetheless, the core finding remained: allocation is best understood not as fixed “plant functional type” rules, but as flexible responses along environmental and trait gradients.

Limitations and next steps

As with any global synthesis, much variation remained unexplained. The models captured the main drivers, but real ecosystems are more complex. Still, the study shows the value of large-scale data in testing theoretical predictions. By aligning empirical patterns with EEO theory, it helps build confidence that models grounded in optimisation principles can robustly simulate global vegetation.

You can read the full paper here:

Ding, R., Nóbrega, R. L.B. & Prentice, I.C. (2025). Global Assessment of Environmental and Plant-Trait Influences on Root: Shoot Biomass Ratios. Global Change Biology, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.70543

REALM: the predecessor to LEMONTREE

This work was funded by LEMONTREE and REALM (Reinventing Earth And Land surface Models). Rodolfo was a former PDRA of Colin’s who worked on the REALM project at Imperial College London. REALM, which ran for five years, laid much of the theoretical and data groundwork for what is now being developed within LEMONTREE, and many of the team continue that work today. This research exemplifies how cross-project continuity is helping refine the theory behind plant carbon allocation.