One of the biological signals emerging from our changing climate is a decline in leaf nitrogen concentrations (LNC) across ecosystems worldwide. For years, this trend has raised concern: Are forests becoming nitrogen-limited? Does lower leaf nitrogen undermine plant’s ability to sequester carbon and buffer us against climate change?

A new study, published in PNAS by researchers from the LEMONTREE project and international collaborators, offers a different perspective that reframes declining LNC not as a symptom of weakening ecosystem, but as a sign of acclimation by plants under rising atmospheric CO₂. These findings suggest that forests may be adapting more efficiently than previously thought, with important implications for how we model the future of carbon and nutrient cycles.

The Traditional View: Nitrogen Decline as a Red Flag

Leaf nitrogen is fundamental to photosynthesis. It’s heavily invested in key enzymes, especially RuBisCO, which captures atmospheric CO₂ in the Calvin cycle. So, it’s no surprise that declining LNC has been interpreted as a signal of nutrient constraint. If leaves are getting less nitrogen, the logic goes, photosynthetic capacity must be declining, and so too must forest productivity. This has supported a long-standing narrative: that enhanced plant productivity with rising CO₂ outpaces nutrient availability, leading to “dilution” of leaf nitrogen and increasing nutrient limitation of the land carbon sink.

But does this interpretation hold up?

The New Eco Evolutionary View: Plants Optimising for Efficiency

This new study, led by Maoya Bassiouni (UC Berkeley), challenges the old assumption. Instead of framing LNC decline as nutrient shortage, they asked: What if plants are simply becoming more efficient under elevated CO₂?

Their answer is grounded in optimality theory. In essence, this theory proposes that plants dynamically allocate resources, in this case nitrogen, in ways that maximise photosynthesis while minimising costs. Under higher CO₂, plants don’t need as much RuBisCO to fix the same amount of carbon. So, rather than investing heavily in nitrogen-rich enzymes, they can do more with less.

This physiological adjustment is known as photosynthetic acclimation.

Bridging Theory and Observation

To test this hypothesis, the researchers examined data from 409 long-term forest plots across Europe, spanning over two decades. They compared observed LNC trends with predictions from a model based on optimality theory that accounts for changes in CO₂, temperature, light, and water availability.

Their key finding? The predicted LNC decline, about 4% per 50 ppm CO₂, matched almost exactly with observed trends over the same period. This agreement supports the idea that observed leaf nitrogen declines reflect optimal adjustments in photosynthetic capacity, not dilution.

Water Stress Matters, Too

While CO₂ was the main driver, the study found that plant water status also played a significant role. Accounting for water stress improved model performance, especially at the plot level. This makes physiological sense: water availability affects stomatal behaviour and carbon uptake, which in turn influences how much nitrogen a leaf can uptake and needs for photosynthesis.

Both water stress and vapor pressure deficit (VPD) together explained a substantial share of the variability in LNC patterns, underlining the importance of ecohydrological controls on nitrogen allocation.

What About the Future?

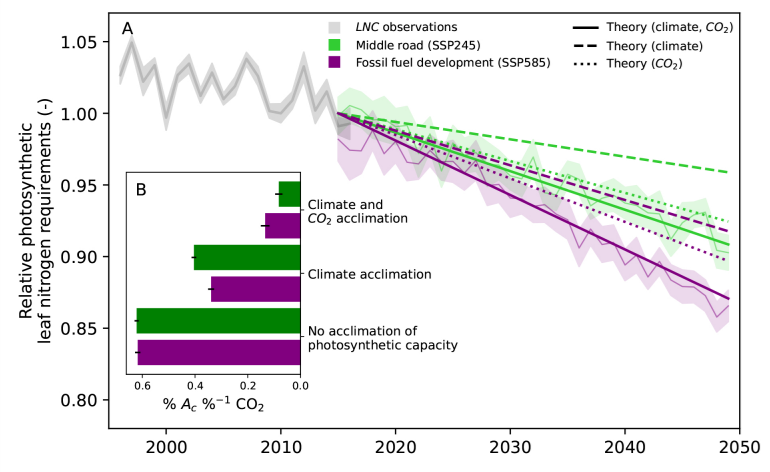

Using climate projections under two future scenarios—SSP245 (moderate) and SSP585 (high emissions)—the study extended its framework to predict future LNC trajectories. The results suggest that leaf nitrogen requirements for photosynthesis will continue to decline as atmospheric CO₂ increases, especially under the fossil-fuelled development pathway.

Interestingly, while CO₂ was the dominant driver historically, climate is expected to play a bigger role in the future—potentially accounting for about half of the projected decline in photosynthetic nitrogen demand by 2050. This suggests more complex interactions between CO₂ and climate variables (like temperature and VPD) in shaping plant resource use strategies.

Why This Matters for Models and the planet

Current Earth system models typically assume fixed or only weakly responsive photosynthetic capacities under rising CO₂. They often miss the dynamic, efficiency-driven downregulation captured by this study. That oversight can lead to overestimations of both nitrogen limitation and CO₂ fertilization effects on photosynthesis.

In fact, this study shows that failing to account for acclimation could result in models predicting 2.5 to 5 times greater increases in RuBisCO-limited photosynthesis under future CO₂ scenarios than is likely. This kind of error has major consequences for how we estimate carbon uptake and predict climate feedbacks.

By integrating eco-evolutionary principles into global models, especially the optimal balance of nitrogen and water costs, we can better simulate real-world ecosystem responses.

Rethinking Nutrient Limitation

This study presents a “efficiency-centric” perspective that challenges the long-held “limitation-centric” narrative around leaf nitrogen response to CO2. If plants can reallocate nitrogen away from leaves when it’s not needed for photosynthesis, then a decline in LNC isn’t necessarily bad. It may simply mean nitrogen is being used elsewhere, perhaps in roots, wood, or reproductive structures, or that uptake is scaled back altogether to reduce energy expenditure.

In this view, nitrogen isn’t missing; it’s being used more efficiently. This is a powerful reframing of what many have seen as a troubling trend.

Rather than treating declining LNC as evidence of system failure, this study invites us to consider it as evidence of system optimisation, a sign that plants are adapting, not deteriorating. That perspective doesn’t eliminate concerns about nutrient cycling or forest health under global change. But it does remind us that nature is dynamic and responsive, and our models need to be too.

Building on previous work

Citation

Bassiouni M., Smith N.G., Reu J., Peñuelas J., & Keenan T.F. (2025). Observed declines in leaf nitrogen explained by photosynthetic acclimation to CO₂. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122 (33), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2501958122