Plants face a constant challenge: adapting their leaves to ever-changing environmental conditions while maximising their ability to capture carbon through photosynthesis. But how exactly do leaves adjust their key traits in response to changes like rising CO₂ levels or drier air? And how quickly do these adjustments happen?

In our recent study led by PhD student Astrid Odé, we explored these questions by identifying crucial leaf traits, understanding their response mechanisms, and modelling how these traits change over time. Our work bridges the gap between plant physiology and ecological modelling, offering new insights to improve predictions of how vegetation will respond to global change.

What Are Leaf Traits and Why Do They Matter?

Leaf traits are characteristics of leaves that influence their function — such as how they exchange gases, transport water, or carry out photosynthesis. Examples include:

- Stomatal conductance (gs): How many, how large and how open the tiny pores on leaves are (i.e., stomatal density and size), controlling water loss and CO₂ uptake.

- Photosynthetic capacity (Vcmax): The maximum rate at which leaves can fix carbon.

- Leaf mass per area (LMA): A measure of leaf thickness and density, related to leaf lifespan.

These traits don’t act in isolation. Instead, they are tightly coordinated to optimise carbon gain while minimising water loss and resource costs. But importantly, they don’t all respond at the same speed or in the same way.

Different Traits, Different Timescales

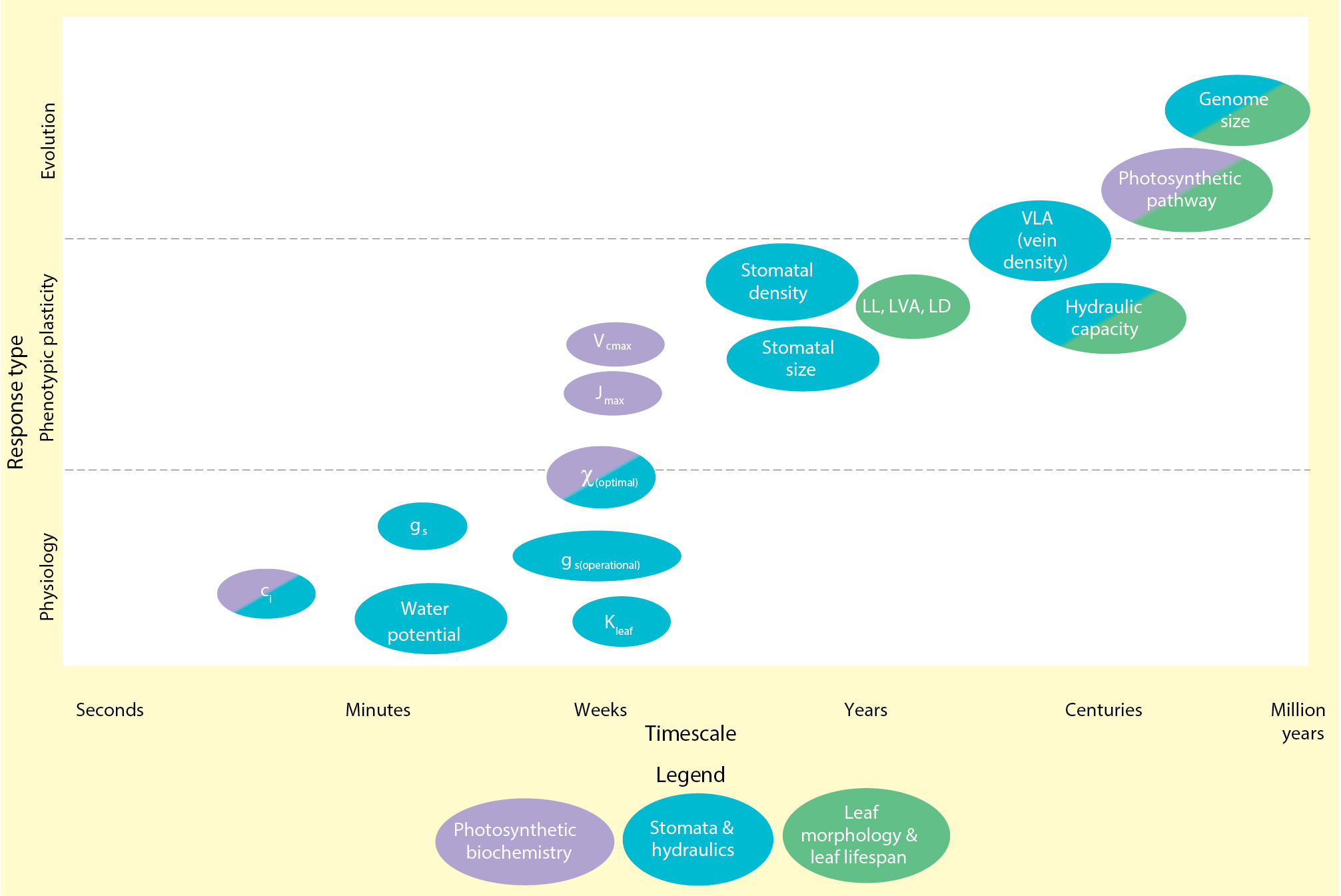

Our literature review uncovered 17 key leaf traits essential for modelling leaf-level eco-evolutionary optimality (EEO) — the idea that plants invest in traits to maximise their fitness in their environment.

We found that:

- Physiological responses happen fast — from seconds to weeks — and include quick adjustments like stomatal opening or closing.

- Phenotypic (acclimation) responses take longer — weeks to months — involving biochemical shifts like changes in enzyme activities or leaf structure.

- Evolutionary changes occur over thousands to millions of years, shaping long-term constraints like leaf anatomy.

This separation in timescales is critical because it means models must account for how traits adjust immediately versus how they acclimate or evolve over time.

Modelling Leaf Responses to CO₂ and Humidity

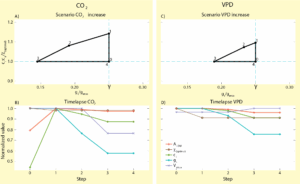

As a proof of concept, we simulated how key leaf traits respond to sudden increases in CO₂ and vapor pressure deficit (VPD, a measure of air dryness).

- When CO₂ levels doubled from 400 to 800 ppm, leaves showed an instantaneous increase in internal CO₂ concentration (ci) and a decrease in stomatal conductance (gs) to save water.

- Photosynthetic capacity (Vcmax) then adjusted downwards over weeks to months, balancing carbon gain and resource investment.

- On longer, seasonal timescales, maximum stomatal conductance (gsmax) adjusted to optimise gas exchange under the new conditions.

Similarly, an increase in VPD triggered rapid stomatal closure to prevent leaf drying, followed by biochemical acclimation of photosynthetic capacity and longer-term developmental changes.

These asynchronous but coordinated trait responses help leaves optimise their function step-by-step under changing environments.

Why Coordination Matters

Our results emphasise that changes in one trait often require adjustments in others. For example, boosting photosynthesis demands increased hydraulic capacity to support higher water loss through stomata.

A key mechanism underlying this coordination is cell size, which correlates with genome size. Smaller cells (and genomes) allow denser packing of veins and stomata, enhancing CO₂ diffusion and photosynthesis. This coordination spans multiple traits — veins, stomata, mesophyll cells — linking anatomy to physiology. However, we don’t fully comprehend this mechanism yet and there are likely other mechanisms at play linking the traits, such as cell developmental processes and (cell level) trade-offs.

Differences Across Leaf Types and Life Histories

Not all leaves respond the same way:

- Needle-leaves generally have lower photosynthetic rates and hydraulic capacity than broadleaves due to different vein anatomy and stomatal traits.

- Evergreen vs. deciduous leaves differ in leaf mass per area and lifespan, influencing their response strategies.

Accounting for these differences in models can improve accuracy and help predict how diverse plant species will adapt to environmental shifts.

Improving Vegetation Models

Our framework highlights the importance of separating trait responses by timescale and mechanism — from instantaneous physiological changes to slow developmental and evolutionary constraints.

While our current approach focuses on the leaf level, integrating whole-plant traits (roots, allometry, resource allocation) and evolutionary processes will further enhance predictions.

Ultimately, by connecting detailed plant physiology with broader ecological models, we can better forecast vegetation dynamics under climate change, improving ecosystem management and conservation strategies.

You can read the full paper here:

Odé, A., Smith, N.G., Rebel, K.T. & De Boer, H. (2025). Temporal constraints on leaf-level trait plasticity for next-generation land surface models. Annals of Botany, mcaf045, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcaf045