In the tranquil city of Jena, Germany, scientists from diverse backgrounds gathered from May 12 to 16 to discuss how satellite and remote sensing techniques could enhance observations of the global carbon cycle in the context of climate change. Wenjia (Shirley) Cai, a Postdoc from LEMONTREE, participated in the EEBIOMASS workshop to learn from the latest remote sensing techniques for better validation and evaluation for modellers in LEMONTREE group.

Leading scientists from the Max-Planck Institute introduced radar remote sensing as a comprehensive method for examining land surface and terrestrial vegetation dimensions, followed by practical exercises in tree height inversion and model-data assimilation. Just days after the European Space Agency (ESA) launched the BIOMASS mission, we had the opportunity to hear the latest updates from this promising initiative aimed at revealing tropical forests hidden beneath thick clouds.

Theoretical understanding of radar remote sensing

Remote sensing satellites can be classified as either active or passive based on whether they have their own energy source. Their detection capabilities depend on the wavelength of their onboard sensors. Active radar remote sensing satellites typically operate on X to P bands outside visible light, allowing them to observe structural dimensions from several centimeters (leaves) to nearly one meter (thick stems). Since they carry their own energy source, radar satellites don’t rely on sunlight like optical sensors do. Their radar waves can penetrate thick clouds and even volcanic ash, enabling all-weather operation.

Changes in land surface, including forest canopy structure, are measured through SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) Interferometry, or InSAR. When a satellite passes over a forest from two different positions, it receives slightly different signals—similar to taking two photos of a scene from different angles. By comparing these two wave patterns, we can compute topography and generate digital elevation maps (DEM). Moreover, by flying over a location in different directions, we can detect not only the canopy top but also the layers within it, revealing the forest’s 3D structure.

Hands-on exercise

After two days of theories and equations, attendees had the opportunity for hands-on practice. The practical exercises included: (1) visualizing forest biomass and land cover data in QGIS to analyze whether biomass changes were induced by land use change; (2) calculating forest height inversion using InSAR coherence and validating against LiDAR GEDI data; and (3) working with simple forest growth and demography models (forest gap models), using model-data assimilation to improve model parameterization.

The step-by-step practical exercises enhanced our understanding of radar remote sensing through case studies that built upon the knowledge from earlier lectures. Though these were simplified examples that may not fully represent real-world applications, they sparked our creativity and provided valuable experience for applying radar remote sensing techniques in our future projects.

Exchanging ideas through poster session

Prior to the summer school, attendees were asked to bring posters showcasing their current projects to share with scientists at the Max-Planck Institute and receive valuable feedback. The poster session allowed us to explain our work to people from diverse backgrounds, deepening our understanding of our research and related fields. Through these exchanges, we discovered previously unconsidered ideas and identified new research gaps and questions, helping to guide our next steps.

I feel truly inspired after the poster session, not just because I received valuable feedback for my project, but also because I loved talking to people from different fields who use different terminology. We discovered we’re working on similar issues that we could tackle together. This collaborative spirit encourages me to push forward, knowing there are many like-minded people out there.

-Wenjia (Shirley) Cai, Postdoc at Imperial College London

New mission, new perspective

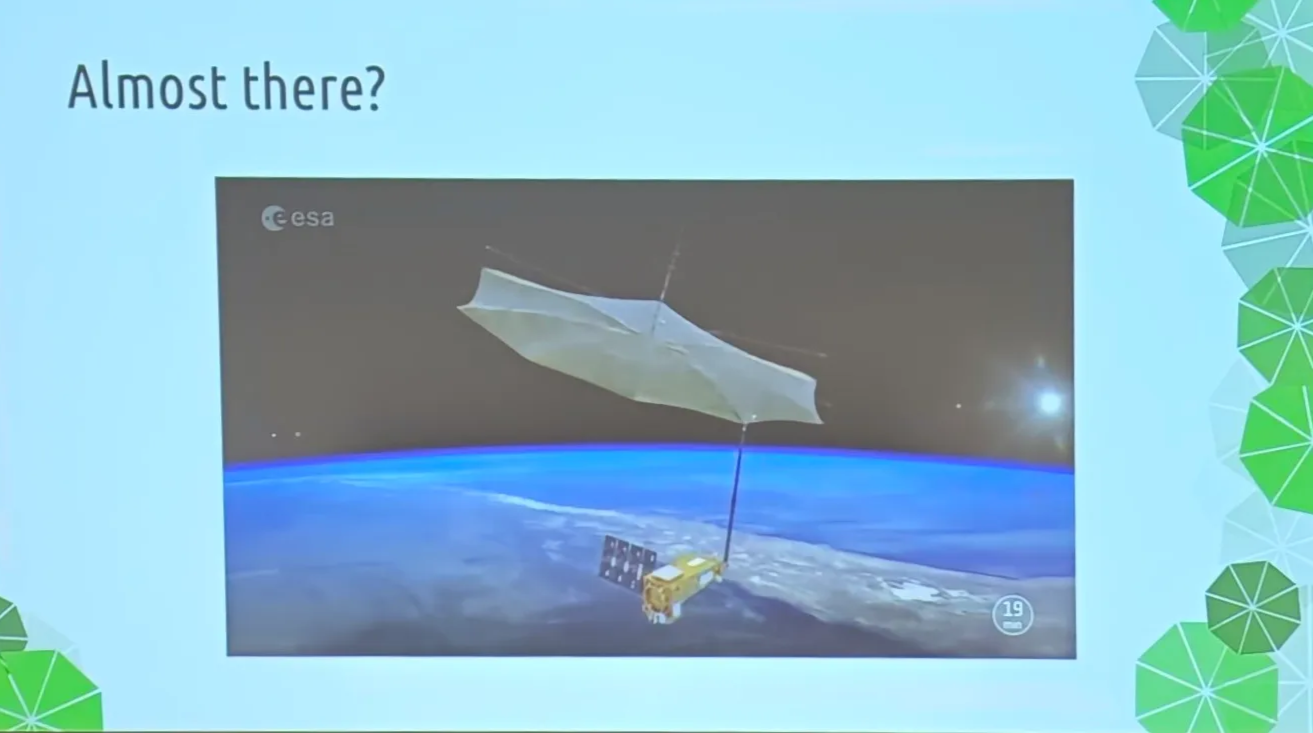

On April 29th, ESA successfully launched the BIOMASS satellite, marking the beginning of its mission to deliver insights into dense forests. BIOMASS is currently the only satellite operating at the longest wavelength (P-band), enabling it to penetrate even the densest forests with thick canopies. While previous satellites could only “see” partially through dense forests and generally saturate at stem volumes around 300 m³/ha, BIOMASS is expected to significantly improve forest biomass estimation in tropical regions. Moreover, full penetration will allow scientists to use scattering power directly instead of stem volume to calculate above-ground biomass, potentially reducing bias in current estimations.

At present, BIOMASS is still in its commissioning phase, so the first batch of data won’t be available until next January. Nonetheless, it’s worth the wait!

By Cai Wenjia