New research led by LEMONTREE PhD student Jan Lankhorst reveals how plants balance carbon, water and nutrient use under different soil conditions.

How efficiently do plants use their resources to grow and photosynthesise? This question sits at the heart of LEMONTREE’s goal: to understand the rules that govern plant function and feed them into the next generation of land-surface models.

A new study published in AoB Plants led by LEMONTREE’s PhD student Jan Lankhorst (Utrecht University) and colleagues provides new insights into how plants balance their investments in nitrogen, water, and carbon under varying nutrient conditions. The findings show that while nutrient availability increases photosynthetic capacity, it does not alter the fundamental balance between carbon and water costs that plants optimise in response to climate.

This discovery reinforces one of the central assumptions of Eco-Evolutionary Optimality (EEO) theory, that plants optimise photosynthesis based on climate and the trade-off between carbon gain and water loss, but also points to refinements needed to account for nutrient effects on photosynthetic capacity.

Testing optimality under different nutrient conditions

Most EEO-based models predict photosynthetic capacity from climate alone, assuming that plants are perfectly tuned to their environment and that their trade-offs between carbon gain and water loss depend only on temperature, light, and humidity. However, acquiring nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus also requires carbon investment, and those costs may influence how plants allocate their resources.

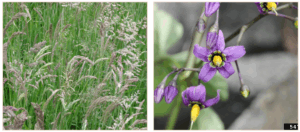

To test how different soil conditions, and subsequent nutrient acquisition costs, influence photosynthetic responses as defined by EEO theory, the team grew two common European species; Solanum dulcamara (bittersweet nightshade) and Holcus lanatus (Yorkshire fog grass), under three levels of nutrient availability, both in sand (with controlled nitrogen and phosphorus fertilisation) and in natural soils that matched those nutrient conditions.

They formulated two clear hypotheses:

- Increasing plant-available nutrients will decrease the carbon costs to acquire nitrogen, driven by a larger increase in whole-plant nitrogen biomass than in root carbon biomass.

- Increasing plant-available nutrients will decrease leaf-level χ values, by decreasing the leaf-level costs for maintaining carboxylation compared to transpiration.

At the end of the experiment, plants were analysed for:

- photosynthetic capacity (Vcmax) — the maximum rate of carboxylation by Rubisco;

- leaf carbon isotope ratios, from which χ (the ratio of leaf-internal to ambient CO₂, ci/ca) was inferred; and

- plant-level carbon cost for nitrogen acquisition, estimated from the ratio of root carbon to total nitrogen biomass.

This design allowed the researchers to link leaf-level optimality with plant-level nutrient costs across controlled and natural environments.

Nutrients increase photosynthetic capacity, and lower acquisition costs

The first hypothesis was clearly supported. As nutrient availability increased, plants grew larger, accumulated more nitrogen, and required less carbon investment below ground per unit of nitrogen gained. In other words, the carbon cost of acquiring nitrogen decreased with increasing nutrient supply.

This finding held across both sand and natural soils, suggesting that the effect was driven by nutrient supply itself, rather than by differences in soil type or microbial composition.

The second hypothesis, however, was not supported. Despite substantial changes in nutrient availability and photosynthetic capacity, plants maintained a stable χ (ci/ca ratio) — the balance between CO₂ assimilation and water loss. Rather than shifting their water-use efficiency, plants increased photosynthetic capacity and stomatal conductance in tandem, preserving the same operational balance between carbon gain and water cost.

This stability supports the least-cost optimality principle at the heart of EEO theory: under a given climate, plants maintain a near-optimal ci/ca ratio that minimises the combined costs of acquiring carbon and water. Nutrient availability changes the magnitude of photosynthetic capacity but not the underlying rules of optimisation.

Decoupling nutrient effects from climate-driven optimality

The results revealed a decoupling between plant-level and leaf-level processes.

- At the plant level, nutrient enrichment reduced the carbon costs of nitrogen acquisition, confirming that nutrient scarcity makes resource acquisition more expensive.

- At the leaf level, however, the balance of carbon and water use — expressed as χ — remained constant, regardless of nutrient availability.

This suggests that while nutrient limitation constrains the amount of nitrogen that can be invested in photosynthetic enzymes (and hence photosynthetic capacity), it does not alter the rules by which plants balance carbon and water costs under a given climate.

This finding provides strong experimental support for current EEO formulations while offering valuable parameters for future model refinement.

Why this matters for modelling and global vegetation theory

Current land-surface and vegetation models vary widely in how they represent nutrient effects. Most models assume direct limitation of nutrient availability on photosynthesis..

By showing that nutrient availability affects photosynthetic capacity and plant-level costs, but not the ci/ca relationship, this study provides a clearer pathway for integrating nutrient effects into EEO-based models:

- Nutrient scarcity raises the carbon cost of nitrogen acquisition, potentially limiting photosynthetic investment.

- Nutrient enrichment increases Vcmax without altering the carbon–water trade-off.

- These responses are consistent across species and soil types.

As lead author Jan Lankhorst explains:

“These results differ from some earlier nitrogen-only studies, such as work by co-author Evan Perkowski showing that adding nitrogen alone can shift the balance of photosynthetic resource use. In our case, however, plants received both nitrogen and phosphorus — a combination that supports balanced nutrient uptake. This joint addition appears to increase photosynthetic capacity without disrupting the underlying ‘economics’ of how plants trade off water and nutrients, helping explain why χ remained stable in our experiment”

Optimality-based models (including the P-model) assume that plants set their photosynthetic capacity based on climate alone — essentially, that leaves can always invest enough nitrogen to reach their climate-defined optimum. The results here show that when nutrients are limited, plants may fall short of that optimum, and when nutrients are added, Vcmax rises even though climate stays constant. This doesn’t undermine EEO theory; instead, it highlights that nutrient supply can act as a constraint on the expression of the leaf-level optimum. Climate still defines the optimal Vcmax, but soil nutrients determine whether the plant can actually afford to achieve it.

Towards the full picture of plant economics

The study also opens the door to further questions. Root structural carbon captures only part of the total cost of nutrient acquisition. Plants also invest non-structural carbon, for example through root exudates that mobilise nutrients in the soil. Moreover, phosphorus availability often interacts with nitrogen, influencing both uptake costs and photosynthetic responses.

In this experiment, nitrogen and phosphorus increased together across treatments, suggesting that the observed responses reflect broader nutrient-acquisition strategies rather than nitrogen alone.

Future experiments will need to explore how microbial symbioses — such as mycorrhizal fungi and nitrogen-fixing bacteria — alter these dynamics. These partnerships may reduce nutrient acquisition costs without affecting water uptake, providing a key link between plant-level and leaf-level economies.

Reference:

Lankhorst, J.A., de Boer, H.J., Behling, D.C., Drake, P.L., Perkowski, E.A. & Rebel, K.T. (2025). Nutrient availability increases photosynthetic capacity without altering the cost of resource use for photosynthesis. AoB Plants. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plaf061