Understanding Carbon Use Efficiency

Understanding how vegetation responds to environmental variability is key to predicting the future of the global carbon cycle. One important concept in this context is carbon use efficiency (CUE), defined as the ratio of net primary production (NPP) to gross primary production (GPP). Simply put, it tells us how much of the carbon absorbed by plants during photosynthesis is retained for growth rather than lost through respiration.

Despite its importance, global patterns of CUE and the mechanisms that drive its variation have remained elusive. That’s where a recent study by Luo et al. (2025) comes in. This study synthesises data from eddy covariance flux towers to investigate how CUE varies across ecosystems and what environmental and biotic factors explain this variation. Their analysis spans over 350 sites worldwide, capturing a broad range of vegetation types and climate conditions.

What Is Eddy Covariance, and Why Does It Matter?

Eddy covariance is a micrometeorological technique that directly measures the exchange of carbon dioxide, water vapor, and energy between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere. Flux towers distributed across the globe provide high-frequency observations of CO₂ fluxes, allowing scientists to estimate GPP and ecosystem respiration with remarkable precision.

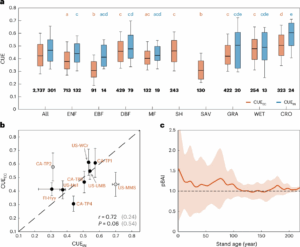

This approach allows researchers to avoid some of the uncertainties tied to remote sensing or model-based estimates of plant productivity. Luo and colleagues used eddy covariance data from 2,737 site-years across 356 flux tower sites, spanning a wide range of biomes, from tropical rainforests to boreal forests.

Key Findings: The Global Average and Its Variability

The study estimates a global mean CUE of 0.43, meaning that, on average, 43% of the carbon assimilated during photosynthesis is used for biomass growth, while the remaining 57% is respired back into the atmosphere.

However, this number is far from uniform across the globe. Luo et al. report substantial variation in CUE across ecosystems, shaped by both climatic factors and plant functional types:

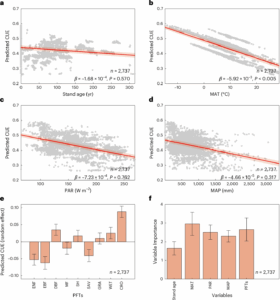

- Temperature: CUE declines with increasing temperature. Warmer ecosystems tend to have higher rates of plant respiration, which reduces the fraction of GPP converted to biomass.

- Precipitation: CUE also declines with increasing precipitation. Although dry conditions may cause a decrease in photosynthesis, but it also reduces the residence time of biomass (less biomass for respiration), which ultimately leads to increase CUE under dry conditions.

- Radiation: Higher levels of incoming solar radiation are associated with lower CUE, possibly due to an increase in respiratory costs associated with construction of new biomass.

- Stand Age: Older ecosystems tend to have lower CUE, highlighting the importance of ecosystem development and successional dynamics.

Temperature emerged as a dominant control. CUE tends to decline in warmer, drier regions, particularly in ecosystems where plants invest more carbon in maintenance respiration or nutrient acquisition. These results underscore the complexity of carbon allocation in terrestrial ecosystems and challenge any assumption of a globally fixed CUE.

Biome Differences: Evergreen vs. Deciduous

An interesting finding of the study is the difference in CUE between plant functional types. Evergreen forests show significantly higher CUE than deciduous forests, likely due to their higher construction cost for leaves that have longer leaf lifespans and thus the higher respiration need to support the construction. This difference has important implications for modelling forest carbon dynamics and evaluating the role of different forest types in carbon sequestration.

Grasslands and croplands, except C4 grass, exhibit relatively high CUE values, reflecting their efficient use of carbon for biomass accumulation and less need for construction respiration cost during growing seasons.

Implications for Earth System Modelling

Most global vegetation models assume a constant or weakly varying CUE. However, Luo et al.’s findings challenge this assumption by demonstrating clear and systematic variation in CUE across biomes and environmental gradients. This could explain some of the discrepancies observed between model outputs and atmospheric CO₂ measurements.

Incorporating these empirical relationships into land surface and Earth system models could improve projections of future carbon dynamics, especially under scenarios of warming and land-use change.

Moreover, this work emphasizes the value of long-term, high-resolution field observations. Eddy covariance data provide a critical benchmark for validating and refining the representations of photosynthesis and respiration in models, two of the largest uncertainties in global carbon budget estimates.

Where Do We Go from Here?

While this study advances our understanding significantly, it also highlights areas where more research is needed. For example, disentangling the role of soil microbial respiration (which is not captured by CUE as defined in this study) could offer a more complete picture of ecosystem carbon balance.

There is also the question of temporal dynamics: how does CUE vary not just spatially, but over time, in response to seasonal cycles, extreme events, or long-term climate change? And how might acclimation or adaptation of vegetation alter these patterns in the future?

As flux networks continue to grow and remote sensing tools improve, integrating these data sources could offer new opportunities for monitoring vegetation health and carbon fluxes at larger scales and finer resolutions.

You can read the full paper here: Luo, X., Zhoa, R., Chu, H., Collalti, A., Fatichi, S., Keenan, T.F., Lu, X., Nguyen, N., Prentice. I.C., Sun., W., Yu, K. & Yu, L., (2025). Global variation in vegetation carbon use efficiency inferred from eddy covariance observations. Nature Ecology and Evolution, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02753-0