Drylands are sprawling regions that cover one-third of the Earth’s land surface. In these regions, rain is infrequent, but when it comes, it doesn’t just nourish plants, it also sparks a sudden, invisible rush of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This phenomenon, long known in soil science as the Birch effect, occurs when dry soils are rapidly rewetted, triggering microbial activity and soil respiration.

A new study led by LEMONTREE’s Ngoc B. Nguyen (a Ph.D. student from the University of California, Berkeley) published in Nature Geoscience, shows that these brief but intense bursts of CO₂ emissions are widely underestimated in ecosystem models and carbon accounting methods. Using a combination of machine learning, eddy covariance data, and a new bias-correction tool called FluxPulse, the team found that rain-induced carbon losses play a far greater role in dryland carbon balance than previously recognized.

Rain pulses: small in time, large in impact

Across 34 dryland ecosystems worldwide, Nguyen and colleagues identified more than 1800 rewetting events using high-frequency data from eddy covariance towers. They found that on average, 17% of annual ecosystem respiration (Reco) and nearly 10% of net ecosystem productivity (NEP) occurs during these short-lived rain pulses, most of which last just a few days.

Yet current models miss a large portion of this carbon flow. Traditional methods show significant underestimations of up to 30% of ecosystem respiration and photosynthesis during rain-pulse events, with rain-pulse events accounting for 16.9± 2.8% of annual ecosystem respiration and 9.6± 2.2% of net ecosystem productivity.

This underestimation occurs because most models assume a gradual relationship between CO₂ fluxes and environmental drivers like temperature and light. But rain pulses are non-steady-state events, and the sharp increases in CO₂ immediately following rewetting don’t conform to these assumptions.

“These CO₂ bursts are short-lived but disproportionately important. By not capturing them, we’ve been missing a major part of the carbon story in drylands” says Ngoc Nguyen.

Understanding the carbon pulses: causes and drivers

The pulse itself has both biotic and abiotic origins. Microbes, long dormant in dry conditions, quickly revive and metabolise newly available organic matter after rainfall. This microbial activity releases CO₂, a biological response known as the Birch effect. Abiotic processes, like the displacement of CO₂ from soil pores, also play a role but are secondary.

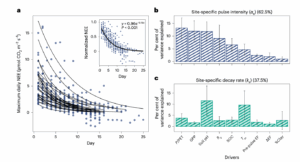

Crucially, the team found that these CO₂ pulses decay in a consistent and predictable pattern, following a universal exponential decay curve across different ecosystems. The average decay rate was 0.16 per day, meaning most of the carbon is emitted within the first few days of a rain event.

“We found that when you normalize the pulse by intensity, all sites converge on the same decay function,” Nguyen explains. “That consistency suggests a shared microbial or soil water dynamic at play.”

What controls the strength of the pulse?

While rainfall triggers these events, precipitation itself is not the best predictor of pulse size or intensity. Instead, the team identified several more important factors:

- Evaporative Fraction (EF): A measure of water availability and ecosystem water use efficiency.

- Pre-pulse net ecosystem exchange (NEE): A proxy for ecosystem activity prior to rainfall.

- Vegetation productivity (GPP) and aridity(P/PET): More productive, less arid sites show stronger pulses.

- Soil pH: Surprisingly, pH is among the strongest predictors of pulse magnitude and decay, likely because of its influence on microbial community structure.

Machine learning reveals the most important environmental features for detecting and characterizing rewetting events are soil moisture dynamics, vegetation activity and pH.

These insights suggest that pulse strength reflects the ecosystem’s “memory”: how dry it was, how much carbon was available, and how ready microbes were to respond. Importantly, not all rainfall results in a CO₂ pulse, especially if antecedent moisture was already high or vegetation uptake quickly balances respiration.

Machine learning and FluxPulse

To accurately detect and quantify these rewetting events, the team developed a machine learning model using a random forest classification algorithm. The model performed best for large “major” rewetting events, i.e., those that result in net carbon losses, correctly identifying over 75% of such events when pulses exceeded 10 µmol CO₂ m⁻² s⁻¹.

Smaller “minor” events, i.e., those where carbon uptake by plants outpaces CO₂ release, were harder to detect, but the team argue that missing these events may not skew carbon budgets as significantly.

One key innovation was the development of FluxPulse, a bias-correction approach that retroactively adjusts traditional CO₂ flux partitioning by accounting for the rain-pulse effect. FluxPulse significantly improved estimates of both Reco and GPP across all sites, offering a practical way to reconcile model outputs with observed carbon dynamics.

Implications for global carbon accounting

Why does all this matter? Because drylands disproportionately influence the interannual variability of the global land carbon sink and they are thought to be expanding.

Yet most terrestrial carbon models don’t include the rain-pulse effect. That means they may be underestimating carbon losses and misrepresenting the resilience of dryland ecosystems to climate change.

As rainfall becomes more intense but less frequent under climate change, these episodic CO₂ losses may increase. Understanding and modelling this dynamic is critical for forecasting carbon–climate feedbacks.

By providing a robust framework for detecting and quantifying these events, this study paves the way for more accurate, climate-resilient carbon cycle models, especially in arid and semi-arid regions.

Conclusion

Drylands are dynamic ecosystems, and rainfall, while infrequent, is a powerful driver of biological activity and carbon flux. Thanks to this new research, we now know that rain-induced carbon losses are both larger and more predictable than previously thought, and its also possible to model them.

By integrating these findings into ecosystem and Earth system models, we can get closer to a truer picture of the land carbon sink, and how it may shift with altered rainfall patterns with climate change.

Citation:

Nguyen, N. B., Migliavacca, M., Bassiouni, M., Baldocchi, D. D., Gherardi, L. A., Green, J. K., Papale, D., Reichstein, M., Cohrs, K.-H., Cescatti, A., Nguyen, T. D., Nguyen, H. H., Nguyen, Q. M., & Keenan, T. F. (2025). Widespread underestimation of rain-induced soil carbon emissions from global drylands. Nature Geoscience, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01754-9