By Alice Ochocka

Monday is often an interesting day at Lynn Museum, because it’s closed. The gift shop is dark, the front door is shut and the Savages carousel, normally lit up and playing jaunty carnival tunes, is silent and still. As the front of house team relax at home on their day off, it’s the curators who open the back door of the museum to researchers and investigators, taking advantage of the lack of visitors to open the cabinets and look more closely at the collection.

On a very cold Monday at the end of November, we welcomed Michael Lewis, Head of Portable Antiquities and Treasure at The British Museum, plus a team of researchers and volunteers. The mission for the day was to photograph, document and analyse metal content of our extensive pilgrim badge collection in preparation for a new publication.

What is a pilgrim badge?

When I walked the Camino de Santiago, an ancient pilgrimage across the top of Spain, I did what most modern-day, weary pilgrims do when they get to the destination city of Santiago de Compostela – ate fried food, drank beer and bought trinkets. This is one of my trinkets – a simple pin badge with the iconic shell design.

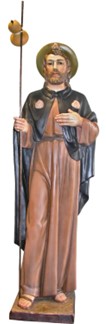

It proves to everyone that I did the walk, it’s a reminder of the experience, and felt like a small treat after two weeks of bunkbeds and blisters. Some people get a shell tattoo, others spend money on jewellery and t-shirts. And early medieval pilgrims did much the same. Natural souvenirs were often popular. In northern Spain, pilgrims collected a shell from the beach, proving they had made it that far. The shells also came in handy as eating and drinking receptacles. The gourd is another item that has become emblematic of the wandering pilgrim, wooden staff in hand with the water or wine carrier dangling from the top.

Leaving behind the hot dusty roads of Spain, we return to west Norfolk, where manufactured pewter badges became popular until the mid 16th century when England’s split from the Catholic church meant a decline in the pilgrimage tradition. But until then, many pilgrims would have traipsed wearily through King’s Lynn on their way to Our Lady’s shrine at Walsingham, just 25 miles away – a veritable pilgrimage hotspot to this day.

Lynn Museum has a particularly large collection of these badges, mostly thanks to local Victorian jeweller, Thomas Pung (1814-1906), who paid children for pilgrim badges they fished out of the mud of the river Purfleet.

Back to the present day, and it’s time to take a closer look at these lead alloy badges.

First thing in the morning, we set up a number of tables as workstations. Lynn Museum curators Jan Summerfield and Dayna Woolbright managed to persuade the fragile and temperamental Victorian cabinets to open and removed the badges from display.

PAS volunteer Rod Trevaskus arrived and set up his impressive digital photographic equipment.

Shortly afterwards, Rob Webley and Owen Humphreys from Reading University turned up and installed the XRF machine on another table. I’d heard of digital cameras before, but I had to admit ignorance as to what an XRF machine was. I now know it stands for “X-ray fluorescence” and is a spectrometer used for analysing rocks, minerals, sediments and fluids. In even more layman’s terms, it tells us about the elemental composition of a thing. For example, most of the pilgrim badges are lead alloys – but just how much lead, and how much other stuff, the XRF was able to tell us.

Gear set-up complete, it was time to switch on the proverbial conveyor belt. Michael and I sat together with a nice grey tray in front of us, with the badges arranged neatly.

We worked one by one, checking the MODES (database) record, double-checking against Michael’s spreadsheet and sometimes consulting the pilgrim badge bible Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges by Brian Spencer. Next, the badge moved along the conveyor belt to Rod who took some photos, before making its final stop at the XRF station. At which point it was returned to its display cabinet.

It was a real joy to work with these experts to learn about their research methods and procedures, and also to swot up on the history behind the badges themselves. Some of them are incredibly intricate and beautiful, with very fine detail portrayed on a small scale.

The pilgrim badge featured at the beginning of the post is a particularly special example. It depicts the statue of Our Lady of Walsingham, ‘the most sacred image of medieval England.’ The Madonna is seated on a throne and holds the infant Jesus on her arm. The reverse view on the right shows the pin which would have attached the badge to clothing.

Working with researchers during the traineeship has been incredibly rewarding – there’s something immensely satisfying about seeing the collection brought to life by experts and impassioned researchers, knowing that the work they do will increase access and benefit so many people. At times it feels like I’ve have stepped behind the scenes on the set of a history documentary and anyone who knows me will know that is a compliment of the highest degree.

You can read Michael’s account of the project here: Recording Lynn Museum’s Pilgrim Badges – MeRit: Medieval Ritual Landscape Conference