The MeRit team has been piloting statistical methods to identify clusters of public finds that may reveal ‘persistent places’ in the landscape (after Daubney 2015/2016), locales where medieval activity appears to focus on earlier monuments.

We are testing various ‘big data’ approaches to look for patterns within the hundreds of thousands of metal-detected finds in the Portable Antiquities Scheme in England and Wales database, to reveal rich time-depth in medieval landscapes. We’ve used a method that was developed by Anwen Cooper and Chris Green for the English Landscapes and Identities project to identify above normal concentrations of reported public finds.

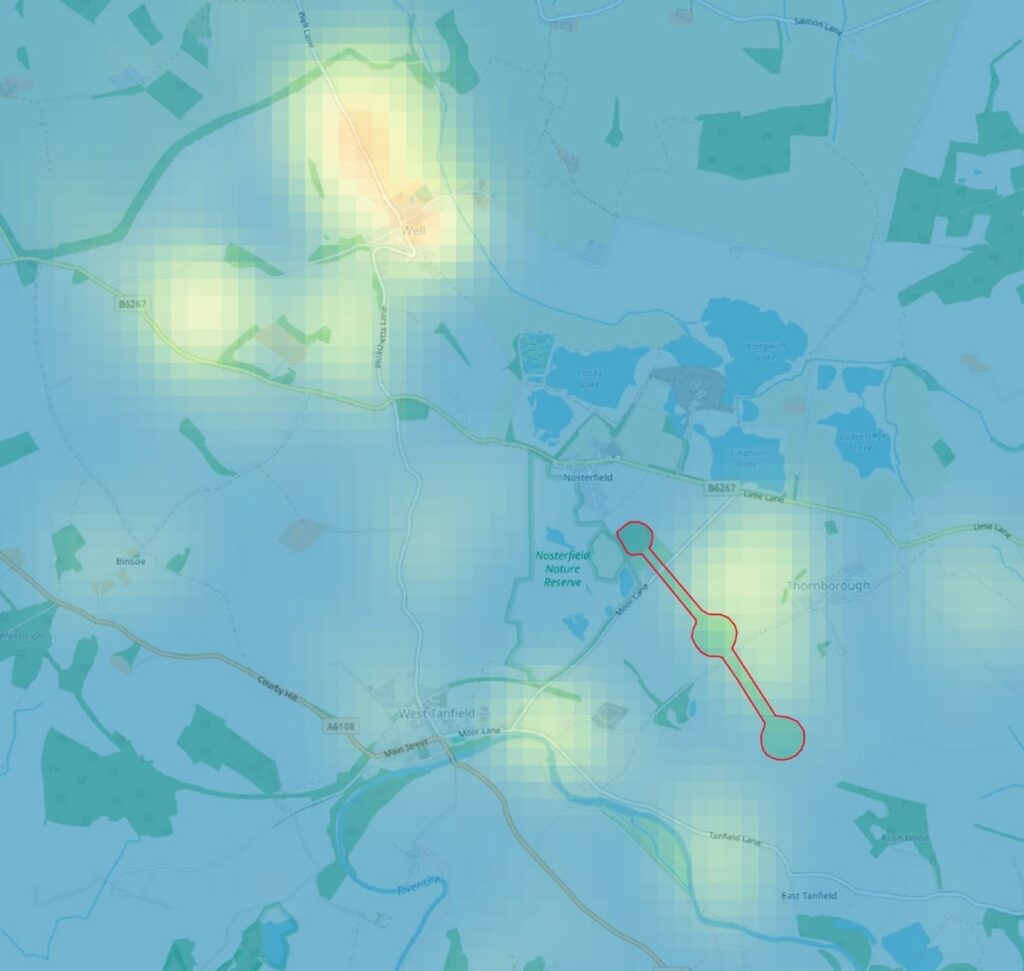

We compared local clusters against a computed regional density average, with the results adjusted to take account whether the finds were recovered on agricultural land (therefore very common) or in other contexts. We tested this approach in our pilot of North Yorkshire to see what local clusters would, statistically speaking, ‘pop out’ from the data.

This identified a significant cluster associated with Thornborough Henges, an extremely important Neolithic and Bronze Age complex. Metal-detectorists have reported 252 public finds here, of which 143 date to the later medieval period (c. 1000–1600 CE). These focus to the north and east of the main earthworks in a space enclosed by a semi-circle of barrows. Why would medieval objects cluster on Thornborough?

Thornborough Henges is a ritual landscape dating from 3500 to 2500 BCE, commonly known as ‘the Stonehenge of the north’. It consists of three giant, circular earthworks each about 250m in diameter, the northernmost covered with trees. The massive circular banks were once up to 4m in height and covered with white gypsum, with internal and external ditches and opposing entrances (Harding et al 2013). Even though much degraded by the Middle Ages, they must have retained a commanding presence in the landscape. When the tenurial structure of the area was reorganized during the Central Middle Ages each nearby township was given its “own” henge.

Local folklore suggests that the site was even used as a tilting ground for medieval jousting! We might dismiss this as a romantic notion, but one of the medieval finds is a rare example of a martial artefact: a knuckle guard for a medieval gauntlet is one of only 10 in the PAS, lending some credibility to this local story.

We also see large numbers of lead spindle whorls at Thornborough, dating from the 13th to 15th centuries, and corresponding with the peak in the Yorkshire textile trade. These objects were closely associated with women’s spinning in the home, but spinning could be carried out anywhere, including in the open air. The density of medieval finds could result from fairs and other assemblies, but could the cluster of spindle whorls suggest that Thornborough was also an important landmark for social gatherings of medieval women?

Main image: Incomplete medieval gauntlet knuckle guard, dating c. 1350–1430 (PAS: YORYM-53CBE2)

Roberta Gilchrist and Eljas Oksanen