“Civilisation depends upon science and high technology, yet most of us are excluded from the language, value and methods of science. This is a recipe for disaster.” Carl Sagan

Carl Sagan was not only an astrophysicist, cosmologist and astrobiologist but a spectacular science communicator who brought the universe into the homes of many through his popular science books and TV series. Why was he respected by so many people? Perhaps because he was acutely aware that the language of science was a significant barrier for many and he made it his life’s work to share his own passion for science in a way that touched people’s lives.

Jump straight to:

- What we mean by language

- The voice of an educator

- The voice of a community leader

- The voice of a policy maker

- The voice of an academic

- Key lessons

Language- it’s all foreign to me

While I believe I have a fairly good handle on the English language, I always find it helpful to look at a dictionary definition to check that my understanding is in line with the standard meaning. So, how about defining the word ‘language’ itself:

“The system of spoken or written communication used by a particular country, people, community etc., typically consisting of words used within a regular grammatical and syntactic structure; (also) a formal system of communication by gesture, esp. as used by the deaf’” Oxford English Dictionary (OED) 2018

In looking up the definition, I was immediately struck with a barrier; the OED site requires you to log in. Granted you can access the free services through your library subscription, but even in the pursuit of finding out information about language itself there are hurdles to jump over. How then, do we stand any chance when confronted with the array of different languages out there?

We can all recognise the barriers that regional languages can play. I, for example have been attempting to learn Spanish since I was 11 and I still can’t muster more than a few sentences. However, I am particularly interested in the part of the OED definition referring to particular communities. It is perhaps natural that with any group who have something in common, familiar words are used to describe a particular item or activity. For example, where I live in Dorset, the dialect word for egg collecting is ‘aggy’ however in the scientific community in which I work the ‘oology’ is the hobby of collecting wild bird eggs (now widely illegal). To many people these words would mean nothing, herein, we have the familiar beast ‘jargon’. While factually, jargon is simply the vocabulary used by a particular group, it is however, often used in a negative light to describe ‘writing that one cannot understand’, ‘pretentious vocabulary’, ‘gibberish’ and it automatically excludes certain people from partaking in the conversation.

We can all recognise the barriers that regional languages can play. I, for example have been attempting to learn Spanish since I was 11 and I still can’t muster more than a few sentences. However, I am particularly interested in the part of the OED definition referring to particular communities. It is perhaps natural that with any group who have something in common, familiar words are used to describe a particular item or activity. For example, where I live in Dorset, the dialect word for egg collecting is ‘aggy’ however in the scientific community in which I work the ‘oology’ is the hobby of collecting wild bird eggs (now widely illegal). To many people these words would mean nothing, herein, we have the familiar beast ‘jargon’. While factually, jargon is simply the vocabulary used by a particular group, it is however, often used in a negative light to describe ‘writing that one cannot understand’, ‘pretentious vocabulary’, ‘gibberish’ and it automatically excludes certain people from partaking in the conversation.

Controversial statement alert! The scientific community for example, are not known for their communication skills and frequently use jargon when describing their findings. I say this, having a scientific background myself, with the intention not to offend anyone and the caveat that there are of course many fantastic communicators out there as the likes of Carl Sagan, Brian Cox and Alice Roberts clearly demonstrate. There is also an increasing recognition of the importance of this in the professional field: there are Science Communication Masters courses available now, many undergraduate courses build communication modules into timetables and indeed our very own Opening up science for al

l!, will soon be launching a course for training academics.

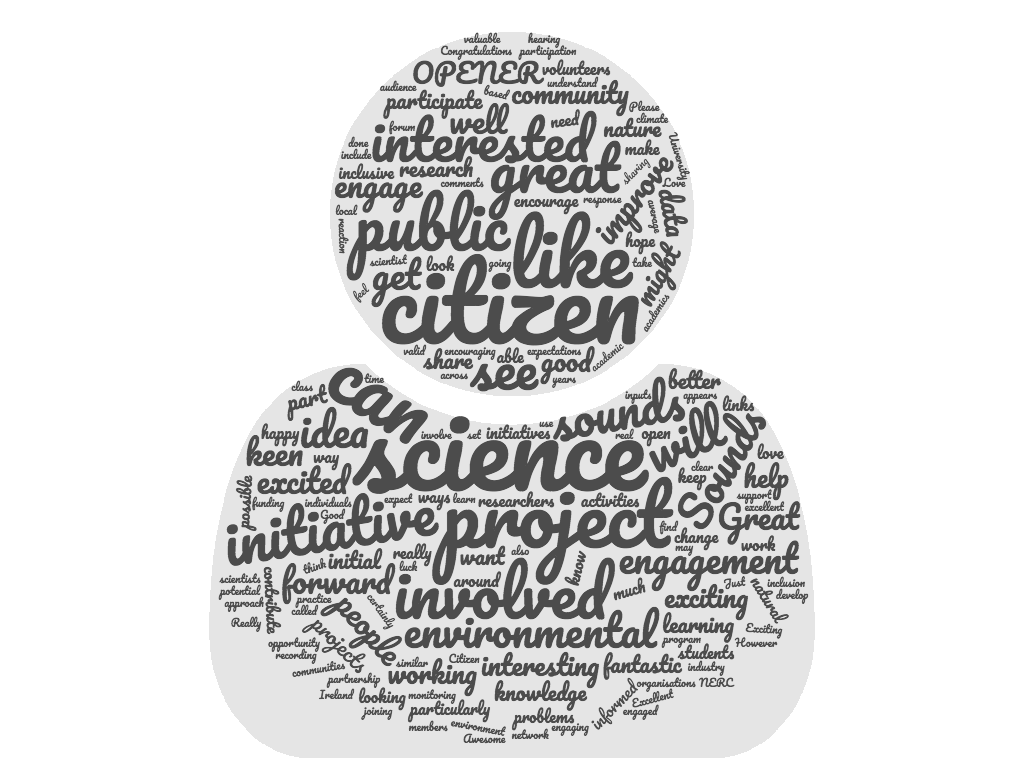

Citizen science is perhaps the shining example of where the pursuit of knowledge is becoming more democratic than ever. Yet, sitting at the crossroads of science, policy and society, there are the inevitable challenges of communication between these communities who each have their own subject matter dialects. To investigate and break down these barriers is indeed the remit of the Opening up science for all! project and one of the key factors that we see as preventing science from opening up further, is the failure to communicate between sectors.

While I could bury my head in the books and give you a fully referenced list of resources in a standard academic report, I feel this may be rather contrary to the conversation we are trying to start. Plus, sometimes written accounts just don’t capture the array of knowledge out there. This is particularly the case as the articles are likely to be written by researchers and authors who, by their very nature, are just one sector of society. I therefore wanted to hear first-hand from a teacher, community leader, policy maker as well as academic about what role they think language has in providing an open forum for discussion about science. Here’s what they had to say:

The voice of an educator

I spoke to one astute school teacher from St Alban’s School in Hampshire who had taken part in the OPAL Polli:Nation citizen science survey, developed lesson plans around the theme and together with her students created the #PolliPromise campaign to support pollinator habitat. She had a number of insightful points to

make about using scientific language in the classroom, her experience of engaging with parents and her own quest to take part in monitoring.

“Our KS1 pupils love words like proboscis (accompanied by long slurping sounds, naturally)”

This quote clearly shows that while our tendency would be to tone down the vocabulary for younger students, the key here is that it is not the terms themselv

es that are the problem, but the explanation around them that should be considered carefully. Primary pupils love big words. There is an old adage that ‘a picture can paint a thousand words’, here, I believe that a word can describe a whole thesaurus of details (assuming of course, that you know what it means in the first place.) For example, the word proboscis conjures up images of insects sipping up tasty nectar through their straw-like mouth pieces, yet when you investigate a little further, it describes the morphological mouth parts of a certain species of butterfly that consists of two tube-like muscular structures hooked together.

“Essentially, children do not usually come with a fear of outdoor learning or getting things wrong and their sheer enthusiasm overrides any hesitations. They, as you know, learn by doing. I often give them the analogy of learning to play a new board game; you can only absorb so many rules before you play and the best way to learn the game is, quite simply, to play it.”

There isn’t much additional explanation needed here, the quote says it all, except to say that while big words may be exciting, it is not only the language which engages students, but the taking part that allows an enriched appreciation of the topic.

Knowing who you are interacting with is essential as each group will come with their own set of motivations and perhaps even reservations. For parents taking part I citizen science projects, this teacher pointed out that:

“My experience is that many keen adults are actually quite anxious about making errors and ‘messing up the research’ and therefore decline to take part.”

It is therefore incredibly important to explain how surveys have been designed to reduce the chance of error and provide people with enough information to feel confident to take part.

“It can be quite difficult to acquire field skills as an adult. I approached a local secondary school to teach me how to use a sweep net (something I have never used) and their response was that they don’t have any because they don’t have any real space for plants or long grass.”

Even when people are keen to take part, there are not always accessible opportunities. Therefore, for those leading or managing research, I see this as a call for information about how to get involved in research projects that are appropriate for different levels of interest.

The voice of a community leader

There are many community leaders out there who are working at the interface between members of the public and professionals. I spoke with one such inspirational leader from the Black Environment Network who provided a few pearls of wisdom:

“There is a process for scientists to engage with the public meaningfully so that an enduring interest is built over time. Whatever one wishes to offer, it needs to first create a connecting image in the mind of the specific category of people they wish to reach. So, words are doing a different job at each stage.”

This is an interesting notion that relationships need to be built over time and the language used at each stage of this journey is tailored accordingly. So, if a local resident who doesn’t have any background in science is passing a poster about an event in the park, the choice of words is imperative to catch their attention

“For example, the word ‘Bioblitz’ means nothing to most people. Here the job for the words is to get people there. One might put on a leaflet ‘Discover fascinating hidden wildlife with us!”

What I take from this is that while we’re not necessarily selling products here, marketing of the activity is nonetheless useful to garner interest to gain initial interest. The next step up is working closely with communities to nurture the interest and it is the face-to face interaction that often leads to the most meaningful impacts:

“Another route is to spend time visiting community group co-ordinators and explain what is on offer and its significance. Then once people are there, the language used has to accessibly communicate practical information as to the activities on offer, scientific facts and the link to research.”

Resources that can be used beyond a particular discussion, or indeed beyond the life of the project are helpful so that not all is lost once that interaction is over.

“Finally, a display or take away materials linking science and research to how it affects aspects of ordinary life would bring science to life. There have been so many good projects but they tend to come and go. Continuity is everything to build the needed understanding and quality of engagement.”

The voice of a policy maker

Providing insight from the statutory perspective, where democratic governments are shaped by the society which they represent, I had a conversation with a dynamic Civil Servant who works in plant and bee health. While her role isn’t directly in comms, she leads an evidence and policy team and is aware of key techniques employed by her colleagues. She suggested that a very helpful rule to go by when reaching the ‘general public’ is to

“Use active, inclusive language and try and pitch it at the level that a 14 year old would understand.”

This ensures that experienced readers are not patronized yet still is understandable to younger members of society.

In a public forum, there is huge potential for people to get the wrong end of the stick, put people off and offend people if appropriate words are not chosen. One of the trickiest situations that she had come across in her time in government was that:

“someone observed that the language we use could be interpreted as anti-immigration. Because in the biosecurity field when talking about pests and diseases, people often use terms like ‘foreign invaders’ or ‘non-native’ etc. Which I thought was a really interesting connection a policy area I’d not really thought about before in relation to plant health.”

The voice of an academic

Last but not least, we hear from a well-regarded NERC researcher who runs a successful lab at Reading University and is keenly involved in developing local communities of practice. Being acutely aware that much of his research is funded by pubic money and that his studies can benefit greatly from a ‘fresh pair of eyes’, he suggests that:

“It is essential for scientists to make their communication relevant to the listener, for example by addressing the ‘so what – why does this matter to me?’ type question. This may mean making the information local, or by providing the implications and context, or by using relevant analogies.”

This chimes well with my belief that the best science communicators don’t need to use complex language to explain their research, they are able to translate their wealth of knowledge in such a way that inspires others to enter into the world of science.

Key lessons

Our linguistic journey has transported us to the school playground, out into community green spaces, over to Westminster and back into the (not so) ivory towers of the university. We’ve heard first-hand from experts in their field and at the end of this whistle-stop tour there appear to be some important themes emerging:

- Avoid jargon. Communicate the wonder of a subject in a way that is accessible for the average teenager.

- Don’t ‘dumb down’ science. While it is important not to over complicate language, it is helpful to pair the correct terminology with a supporting explanation, so that we can all become familiar with a common scientific language.

- Assurance is important for the audience. To reduce anxiety for non- professionals engaging with science, clear instructions should be provided about how to take part in scientific enquiry, how data are verified and what the results mean.

- Language is not the only thing that matters, it is the taking part that may yield the greatest educational benefit. Learning by doing is an effective addition to reading about the subject.

- Direct interaction between people builds trust. Providing support such as bespoke training, ‘taster’ sessions or activity facilitation can be effective because people like to ask specific questions, be guided through the enquiry journey and in doing so build confidence.

- Avoid language that can be misinterpreted. Consider how statements will come across to different audiences, is there the potential to disengage or alienate people? If so, select neutral language.

- Tailor to the listener. People will want to listen to your message if what you are telling them is interesting, relevant to their lives and understandable. This will need to be adapted for different groups and for individuals at different stages of their engagement with science.

We would love to hear about your personal experience of science communication. Perhaps you have taken part in a citizen science survey and found the resources explained the science so clearly you want to run outside and pick up your butterfly net; or perhaps you’re an academic who is thinking of including a public engagement element to your research and are in despair about how to translate your complex research. Whoever you are, please do get in touch so we can work out what our common Opening up science for all! language will be. Please leave a comment below or tweet us @OpenUpSci

Author: Poppy Lakeman-Fraser

2 thoughts on “The Dictionary of Science: What is the role of language in opening up research?”