Is such a Zen-like poem of interest to the physical sciences?

We now live in an era in which the latest development for the justification of investment of resources for the natural environment is Natural Capital Accounting. We are continuously prompted to be practical, to be realistic. It enwraps me in despair that within our governmental structures or our funding frameworks, nature is not at the top of the list because of the way it makes us feel truly and fully alive. Instead, we have to descend to setting ourselves within a bleak list of desperate essentials reduced to the economics of mere physical survival within joyless policies.

These are fundamental mistakes. There have been high profile lessons. They are recent, but the lessons have not been fully learnt. Remember the proposed selling off of the State Forest Estate? The swift reversal was the result of outcries from the heart and not the presentation of a budget spreadsheet. It demonstrated that the ultimate protection for nature and investment in nature is to enhance the linking to the heart within our population. Communication with the public at large must therefore pay attention to the poetic and the emotional that link a range of life meanings to the image of science, and ensure the subtle but powerful thing that is the caring atmosphere within which projects and activities are delivered. The Woodlands Trust’s Tree Charter campaign was a shining example of getting the message. To increase support for the future of trees, they collected over 50,000 personal stories about trees. They realized that people already love trees but it was at the back of their minds. By asking them to share their stories, it brought the engagement of trees to the front of their minds. It stimulated them to act and support the charter.

Years ago, as a young artist, in a conversation with Sir John Vane, joint winner of the Nobel Prize in 1982 for his work on anti-coagulants, he told me how he thought that the general public was sadly entirely misled as to the nature of science. He proposed that the image of science was dominated by the work of applied scientists, who never discovered or created anything, and used the knowledge and skills embodied within science to make money. For him, that popular distorted image of science as a rulebook of fixed formulas and data kills off all the sense of fascination and adventure. Above all, he said to me, “ The real scientists are those who are interested in experimentation, and in new frontiers. They are like passionate poets, willing to leap off cliff edges, taking a risk to journey into the unknown to bring back something new and beautiful. They travel with excitement, observing and discovering aspects of our world that can transform the entire way we see and live life. True science is pure magic!”

Like Sir John Vane said, the popular image of science simply is not that great. What is this science stuff? Isn’t it all extremely boring in that even something really interesting is often reduced to mundane series of obscure facts and figures that ordinary people have not got a hope of understanding? There are still people who think biodiversity is a kind of washing powder. Despite rising awareness, for them the environmental sector still seems to be dominated by jargon, obscure outcomes, and hard work for the benefit of nature with not enough attention to what it all means to people within their lives. On and off projects with no follow-up means interested people experience abandonment at the end of a project. There is an atmosphere that environmental organisations are out to get people to do what they think is really important, and once they have got what they want, they really will have nothing very much to do with the participants at all.

Freud said that in life, we are driven by two great emotions – love and fear. At present, in the context of sustainable development, fear is the aspect that is most used, from climate change to plastics in the sea, it is about how harm will come to us. Yet from research, we know that people do not act as a result of education about the needs of nature or from being informed about threats. The people who make a consistent contribution are motivated to do something for nature out of their love for nature, usually as a result of pleasurable and meaningful experiences at an early age.

After 30 years of working to engage multicultural communities in environmental participation as the Director of Black Environment Network (BEN), I can collapse the whole process of engagement resulting in contribution into single sentence with two phrases.

This two-part sentence starts with pointing to the fundamental importance of access to nature, which for many communities are not privileged to experience. The quality of the experience has to be pleasure, fun, love and meaning. Once people love nature and are informed about the threat to what they love, they all come out fighting for it. They want to participate.

In today’s pressurized lifestyles, how can environmental participation compete? Any image of science and concepts around the protection of nature that does not link into the poetic, the beautiful, or the awe-inspiring is ultimately boring. 21st-century life is, in fact, dulling the senses, and key concepts are reduced to mechanistic proposals to maintain a joyless existence. Take sustainable development. It is all about pulling us from the brink. It is also human centred, framing nature as something that has to be attended to because it props us up. The genius of nature has produced the human being at its pinnacle as the most conscious, creative and potentially its most magnificent manifestation. Yet we are at the same time the most fragile. Our young are helpless for the longest period of time. In any natural disaster or failure of the harvest, we are the first to die. There is every probability that we may destroy ourselves, and that without us, the rest of nature will happily find a new balance, flourishing without us as a destructive force. Nature will always find a way, with or without us.

Our ethnic minority communities, which actually represent the ethnic majorities of the world, sometimes present us with reminders of what a deep connection to nature really means. Some come from settings in which the connection to nature has been nurtured within the culture and the way of life. The following stories nudge us to think about what we have lost and stimulate us to be imaginative about how we may recapture our own richness.

In the early years of BEN, a Bangladeshi group in the Kings Cross area of London wanted to grow vegetables. Land was found for this purpose and at the end of the project, we had to write the usual report required by funders. One of the questions was simply, “What was the best thing about the project?” Instead of the usual expected answers such as fresh air, being outside, having nice fresh vegetables to eat, their answer blew us away. They said, “The best thing is that our bare feet are once more against our mother, the Earth.” As a young woman, many years ago, in the south of the Indian sub-continent, I saw women in the villages create beautiful rhythmic symbols, called Kolams, using rice powder in front of their houses to bless the house. When they finished, to my astonishment, they swept them away so that they may not walk on them. They did not stand in admiration of their handiwork and take a photo, or have any thought that a beautiful image may have commercial value. They were pure acts of spiritual devotion honouring nature.

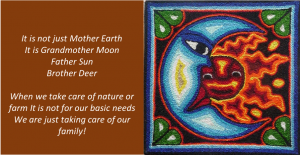

In a recent trip to Mexico, I talked to Huichol Indians. I mentioned Mother Earth, and a young man said, “ Oh, it is not just Mother Earth. It is Grandmother Moon, Father Sun, Brother Deer…when we take care of nature or farm, it is not for getting food to feed ourselves, we are just taking care of our family.”

Such expressions of absolute visceral, emotional and spiritual connection, in all these examples, jar against our usual practical world. And, of course, inspiring, pushing us to rethink emotional connection, motivation, poetic meaning, and the significance of symbols and cultural visions.

Making a shift in how we engage with community and what kind of image we project in relation to the physical sciences as a facet of our lives is both practical and subtle. While operating within a world obsessed with the value of money and where to save it or spend it, we need to work at our own integrity and the whole feel we bring to our projects and activities. Optimistically, there is a movement towards the need to care for each other. The recent recognition of the benefits to health and well-being is a hook for resourcing work that impacts daily life. Still, it is constantly reduced to whether it will save the NHS a lot of money, or whether it saves businesses lost working days and so on as the measure. Such ways of seeing may be justified as practical and realistic, but the manner of delivery of projects and activities that consciously embody and project the true caring for the community is altogether a different kettle of fish. Caring is a word that moves us closer to the word loving. The workers on any project need to be people that truly care for the community. As a result, their work with members of the community will reap altogether a different quality of outcome, where people will engage with nature within their hearts. When I speak of loving in terms of organisational actions and policy, I often bring in the Buddhist term for loving of the highest order. They call it love-wisdom. It is love that is not sentimental but has a quality that combines the sharpness of mind with the purity of heart. For me, one of the most needed and most precious achievements of our era would be to bring the significance of the contribution of sound science together with the passion of people for nature. It would create a force to be reckoned with.

80% of the UK’s population now live in urban areas, and 21st century life is eroding the opportunity for our children to immerse themselves in nature. Our educational system is focused on filling them with information so they can be employed profitably. In those few hours when they are not shut away within four walls, we must create opportunities for them to experience nature in its full beauty and sensuality. Many such efforts do not involve funding. Often it is about how we do things and the quality of an experience. When I look back on my own experience, I can see that what fed me and enabled me to become a poet, artist and environmentalist is the fact that nature itself is unnecessarily beautiful.

From that experience, I know that all the things that give us joy, and make us truly alive and fully alive are in fact the things that are beyond mere survival. They are things that are, by definition, unnecessary.

We need to be poetic environmental warriors on the battlefield, fighting for space within human hearts, projecting an image of the physical sciences that resonates with all that unnecessary beauty and magnificence, having fun and building meaning. That is what, at the very core, will ultimately protect nature and people. The rest are detail.

Judy Ling Wong CBE, Honorary President, Black Environment Network