by Richard Johnson, Lecturer in US Politics, Lancaster University

A full analysis of American politics is incomplete without understanding that the United States has undergone a profound intensification in racially polarised partisanship. Race and attitudes about race closely align with partisan identities more so than at any time in recent history. Barack Obama was elected in 2012 with the lowest support from white voters of any successfully elected presidential candidate; Hillary Clinton did even worse among whites. At the same time, Democrats continue to attract exceptionally high support from racial minority groups.

In the United States, access to the franchise has always been shaped in partisan terms. The politics of suffrage has never been a simple matter in the United States of a progressive expansion of the right to vote. Access to the ballot has been increased and shrunk according to whoever manages to win power to write the rules.

In the nineteenth century, many states allowed non-citizens to vote, advantaging Democratic machines in urban areas. Also in this century, ex-slaves were given the right to vote, and more than 2,000 African Americans were elected to local, state, and federal office in the 1860s and 1870s. Nearly all of these were Republican. As new, whiter western states joined the Union and began voting Republican, the partisan imperative to give blacks access to voting rights decreased. Eventually, the Republicans abandoned their black electors for a newer, whiter crop of voters.

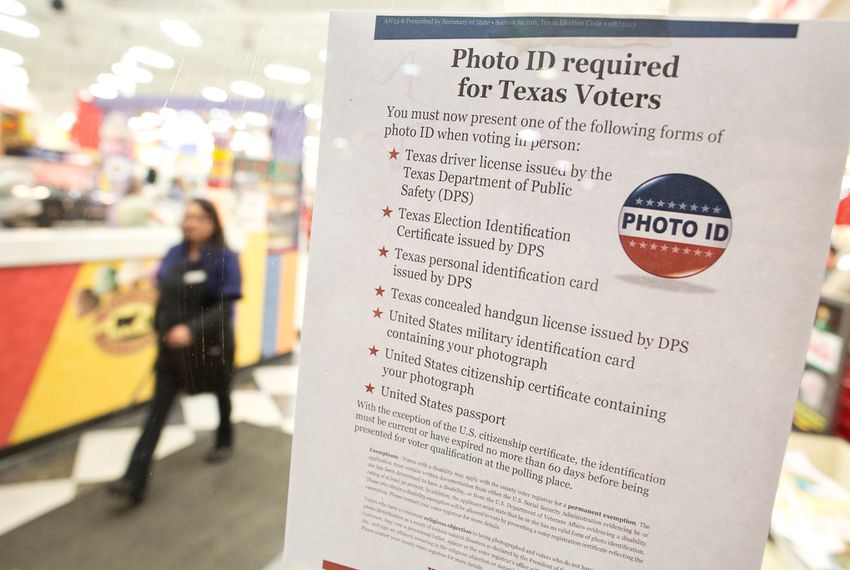

In the twenty-first century, when party and race so closely align, rules written to advantage one party inevitably seek to advantage a race. Rules with seemingly innocuous, race-neutral purposes, such as requiring voters to provide a state-issued photo ID to vote, can have racial and partisan implications if groups have access to those IDs at different rates. In Texas, for example, while 96.2% of white adult citizens have drivers’ licences, only 86.9% of African Americans do. This ten-percentage point gap can be politically consequential in close elections.

This is no accident. The racist laws used to prevent blacks from voting before the mid-twentieth century civil rights movement — such as poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests – were written in race-neutral terms. While it meant that some poor whites were also affected, officials knew that the greater number of voters who were affected were African Americans.

John Knox, the president of the Alabama constitutional convention which ratified the state’s racist post-Reconstruction constitution in 1901, argued that a literacy test existed to ensure that ‘[t]he negro is not discriminated against on account of his race but on account of his intellectual and moral condition.’ In 1945, the Alabama poll tax was $1.50 ($20.20, adjusted for inflation in 2016), which is less expensive than it costs to buy a state-issued photo identification card ($36.25) in Alabama today.

In The Trump Presidency volume, I wrote about the Texas voter ID law, which was challenged by the Obama administration in the courts. After Obama’s departure, the Trump administration reversed the federal government’s position and became a supporter of the legislation. Recently, another racial minority group has been affected by the collusion of a Republican legislature, a Republican Justice Department, and a conservative federal court, with the effect of diminishing a racial group’s access to the ballot for partisan gain.

North Dakota is the only state in the United States which does not have a voter registration requirement. Consequently, voters are required to show proof of residency in the state in order to vote. Until recently, voters without an ID could rely on another proof of residency, such as a sworn affidavit from a voter who did have ID. State Republicans changed the law to require that all voters show IDs which listed a residential address, not a PO Box. These personal post-boxes accessible at a local post office are used by many Native Americans because the US Postal Service does not provide a daily, door-to-door service to some rural tribal communities. A 2015 survey showed that 23.5% of Native Americans lacked the required ID vote, compared to 12% of non-Native Americans.

The law was changed by the state legislature for nakedly partisan purposes. In 2012, Democrat Heidi Heitkamp defeated Republican Congressman Rick Berg in the narrowest of margins. Heitkamp was elected to the US Senate with a margin of 2,936 votes over Berg, a majority of 0.92%. One year before facing re-election in 2018, the Republicans passed the new ID law.

Heitkamp’s victory was secured, in part, due to solid support from the state’s native populations. Native Americans form the largest racial minority group in the state. They also vote heavily Democratic. Sioux County, in the south of the state, is home to the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The county is 84% Native American, and in 2012, it delivered 84% of the vote to Heitkamp. Rollette County, in the north, is home to the Turtle Rock Indian Reservation. The county is 77% Native American and delivered 80% of its vote to Heitkamp.

In April 2018, Daniel Hovland, chief judge of the US District Court of North Dakota, ruled that the law disproportionately negatively impacted Native Americans. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg also warned, ‘the risk of disfranchisement is large’. She observed that 18,000 North Dakotans lacked sufficient documentation to vote under the law.However, on 9th October 2018, the conservative-dominated US Supreme Court upheld the North Dakota voter ID law.

It is important to observe how partisan actors can co-ordinate at multiple levels to achieve desired outcomes. A Republican-controlled state legislature faced no opposition from the Trump-era Justice Department, whereas the Obama-era Justice Department had been active in suing states on behalf of discriminated minority groups.Democrat Heidi Heitkamp won her Senate seat by less than 3,000 votes before the law went into effect. The Democrats are two seats short of a Senate majority. A conservative-dominated Supreme Court protected the legislation from challenge. Small, incremental adjustments to institutional rules can lead to consequential policy changes, as we may soon see again.