by Darius Wainwright, University of Reading

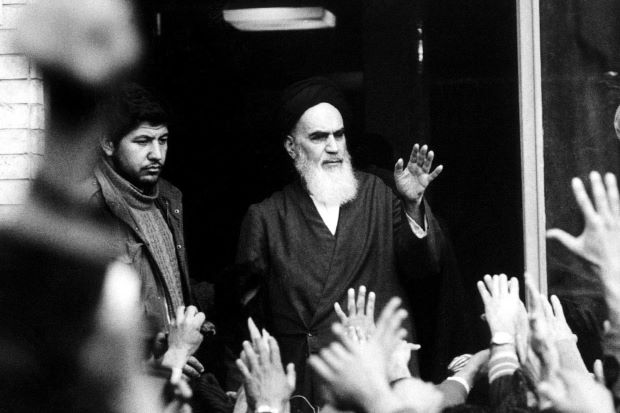

1 April 2019 marks 40 years since the Islamic Republic of Iran was established. Its founding stemmed from the 1979 Iranian Revolution, where the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a U.S. client and ally, was overthrown. From its inception, diplomatic ties between America and Iran have been tense, complex and fractured. The newly installed Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, sought to dampen American influence and culture in Iran, blaming this for the decadence and excesses of the Shah’s regime.

Bilateral relations worsened after November 1979. Angry at the U.S. government’s decision to permit the deposed Iranian monarch to temporarily reside in New York, figures close to Iran’s newly installed Supreme Leader instigated the storming of the US Embassy in Tehran. A violation of hitherto sacrosanct diplomatic conventions, the event was momentous, irreparably damaging U.S.-Iran relations to the present day. The Iranians took 52 hostages, holding them for 444 days. The ensuring stand-off, exacerbated by the daily updates on U.S. television and a failed April 1980 rescue attempt, resulted in the incident becoming engrained in American popular memory.

‘Dealing’ with Iran

Since the Islamic Republic’s foundation, the U.S. government has been unable to dismiss or side-line Iran. In spite of its government’s vehement opposition to America, the country straddles the oil-rich Persian Gulf and Arab world, while also providing a gateway into Central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent. Iran’s geopolitical importance has only heightened in recent years, with the growing Islamic Fundamentalist threat and the ongoing global war on terror. These developments have only served to vex presidential administrations in the White House. All have struggled over the extent to which the U.S. can interact with a regime so vehemently opposed to the American way of life, each devising different, but interrelated, ways in which to ‘deal’ with Iran.

Initially, White House administrations have suffered electorally due to their poor handling of the Iranian question. Presiding over the Iran Hostage Crisis, Democrat Jimmy Carter’s failure to negotiate the release of the U.S. Embassy’s staff in Tehran contributed to his departure from presidential office after just one term. His Republican successors, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, did not fare any better, either. The former was dogged in his second term by the Iran-Contra affair, a scandal involving the alleged sale of weapons to Iran to fund right-wing paramilitary guerrillas in Nicaragua. The latter, inaugurated in 1989, was still beset by his predecessor’s scandal, having served as Reagan’s Vice President.

From the Cold War’s resolution, there have been two juxtaposing strands evident in U.S. foreign policy towards Iran. The first has been the international isolation of the Islamic Republic and the advocation of its overhaul. This policy of regime change has stemmed from the popular American anger and distrust caused by the hostage crisis, an incident much of America’s public and political believe the U.S. has not been adequately recompensed for. Many Americans in Congress and beyond, moreover, are convinced that the values espoused by the Islamic Republic run counter to the norms and values of freedom and democracy that are supposedly championed by America.

Such vehement opposition towards the Islamic Republic compelled certain presidential administrations to adopt a tough, uncompromising approach towards Iran. Bill Clinton, in his first term, implemented the policy of ‘dual containment.’ Grouping the country with its neighbour, Iraq, he strove to starve Iran’s economy and its regional influence. George W. Bush, likewise, used his 2002 State of the Union Address to place Iran, among others, in his ‘axis of evil.’ Throughout his time in office, Bush junior accused Iran of supporting terrorist groups and of working to manufacture a nuclear weapon. He cited the latter as the justification for the tightening of international economic sanctions on the country.

In contrast to this hardnosed stance towards the Islamic Republic, the second key strand in the U.S.’ diplomatic approach towards Iran is much more conciliatory. The standpoint’s key advocates presume that America and Iran share mutual regional goals. These can be collectively achieved if presidential administrations work with supposed moderate Iranian governing elites. With the election of reformist President Mohammad Khatami in 1997, Clinton abandoned the ‘dual containment’ policy, working with his Iranian counterpart to improve U.S.-Iran ties. Barack Obama and his second Secretary of State, John Kerry, built on this further. Between 2013 and 2015, both figures worked with the Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and his Foreign Minister, Javad Zarif, to reconcile America and Iran. Their efforts were rewarded in April 2015 with the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Dubbed the ‘Iran deal’, the treaty pledged that the country would halt its nuclear programme in return for the lifting of economic sanctions.

The Iran deal was part of a broader effort to not just improve U.S.-Iran relations, but also bring together two key powers fighting against the so-called Islamic State. The Obama administration’s rationale for the agreement, however, went beyond just geopolitical self-interest. The U.S. government’s desire to engage with Iran to achieve diplomatic objectives has historical roots, originating during the Cold War. Presidential administrations from Eisenhower to Carter agreed to supply the Shah with considerable military and economic aid to deter the Soviet Union from making any inroads into the Middle East. The Iran deal, then, was a legacy of these pre-1979 collaborative efforts, a throwback to when the U.S. and Iranian governments were allied together in a fight against Communism.

U.S.-Iran Relations Today and in the Future

The U.S.’ adherence to the second conciliatory strand in post-1979 U.S.-Iran relations was short lived. In May 2018 Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the Iran deal. The current American President claimed that the Iranian government flouted the agreement, which its leadership vehemently denied. The reversal of his predecessor’s approach to ‘dealing’ with Iran signalled that the Trump administration would revert to the first strand of American policy thinking towards the country which advocated regime change. Whether Trump’s stance towards Iran will be successful is debatable. For the past 40 years, American presidents have wrestled with the Iran question, adopting an uncompromising or conciliatory tone towards the country, each with limited success. Unless Trump or his successors find another way of ‘dealing’ with the Islamic Republic, the Iran question will be one that will beset all future sitting U.S. presidents.