For our latest LONG READ, we are delighted to welcome Linda Gilroy, MP for Plymouth Sutton 1997-2010. Here Linda details Plymouth’s proud history of supporting women’s politics from suffrage to parliamentary representation in the C21st century.

Plymouth people – including women using their vote for the first time – made history in 1919 when they played their part in electing Lady Nancy Astor as the first woman to take her seat in the Westminster parliament.

Suffrage in Plymouth

The city had always been active in campaigning for votes for women. A petition was sent from Plymouth in 1869 demanding that women should be able to vote. From then onwards, throughout the sixty-year history which led to the 1918 enfranchisement legislation, there was sustained support as Plymouth suffragists and suffragettes campaigned ever more insistently for votes for women. In 1871 leading suffragist Millicent Fawcett spoke at the first public women’s suffrage meeting in the town and two years later in November 1873 Plymouth held a grand meeting. The all-male council voted in support of the Women’s Suffrage Act presented to parliament that same year. In the decades that followed there were regular visits from national and international campaigners.

As people lost patience with the peaceful campaign nationally, so too did Plymouth women. The WSPU, who were committed to “Deeds not Words”, had emerged in 1903 with their campaign of smashing shop windows, blowing up letter boxes and arson attacks on some MP’s houses. In late 1907 or early 1908, a Plymouth branch of the Union was established. Things escalated across the country. In March/April 1913 some eighty suffragette inspired incidents took place across the country. In Plymouth on 10th April a bid to blow up the iconic Smeaton’s Tower lighthouse was foiled when a homemade device was deactivated in the wind. A canister, with “Votes for Women” painted on the side, had been filled with explosive and a fuse attached to it. Suffragette leaflets were found scattered on the Hoe.

Eight months later in 1913 Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst was travelling back to Britain from New York on board the steam ship Majestic. Plymouth was a main port of call for ships from the States in those days.

Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested on board ship before she set foot in Plymouth.

Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested on board ship before she set foot in Plymouth.

Emmeline had been there on a speaking tour, in breach of some bail conditions, set when she had been released from Holloway Prison under the Cat and Mouse Act so she could recover from the effects of her hunger striking. A crowd of over 5,000 people had gathered to welcome her back. Anticipating her arrest, some women, who were trained in ju-jitsu, were prepared to defend their leader with clubs smuggled under their skirts. Fearing a riot, the police set off from Bull Point, a part of the Devonport naval base west of the Port of Plymouth, to arrest Mrs Pankhurst on board ship. She was taken to Dartmouth and Exeter jails and thence back to Holloway prison. A few weeks later her frustrated supporters torched a timber yard in Devonport, causing £12,000 (£1million in today’s terms) in damage.

There remains a debate about whether the efforts of the suffragettes were becoming counterproductive, making women look as if they were not responsible citizens worthy of the vote. In any event the outbreak of war in 1914 saw most of the suffragists and the suffragettes desist from campaigning, with many turning to support the war effort.

Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act

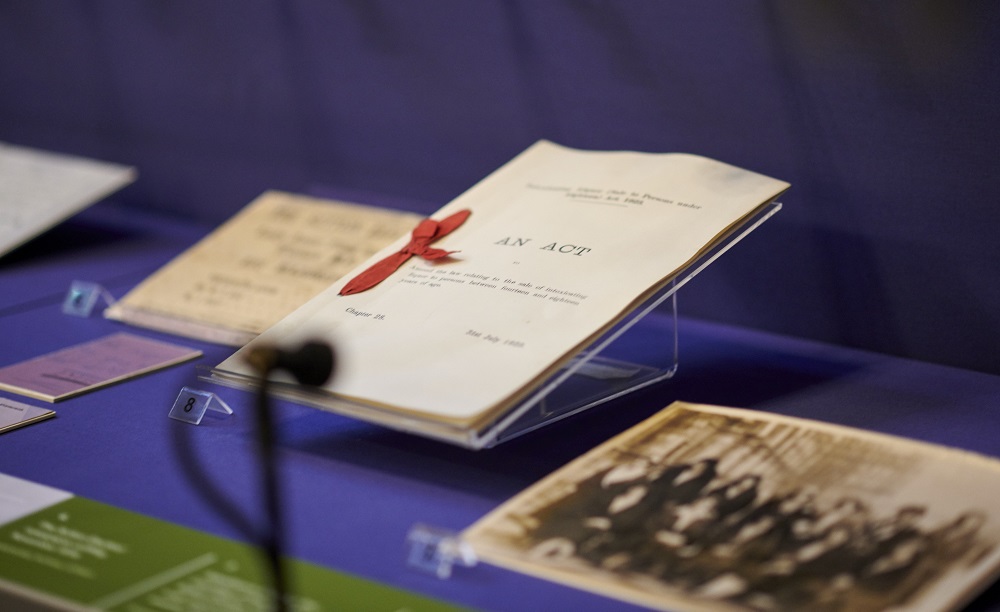

The end of the war brought with it strong pressure for universal suffrage for men over the age of 21 and those over 19 who had seen active service. The 1918 legislation which enacted this also made provision for votes for women, but broadly speaking only for those over thirty with a property qualification. This enfranchised about two in every five women. That year also saw the rather hastily enacted one sentence, 27-word Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, which enabled women over 21 to stand in the 1918 general election.

Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 image courtesy of Parliamentary Archives

Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 image courtesy of Parliamentary Archives

It was passed on November 21st and left precious little time for any women who wanted to stand to get organised for an election on 14th December. Emily Frost Phipps, born to a Devonport Dockyard coppersmith father and seamstress mother in 1865, at Southview Buildings, Stoke Damerel was one of them. When she left school, Emily taught infants in Plymouth. Over the years as she progressed in her career and eventually became a head teacher in Swansea, she became active in the NUWT campaigning for equal pay and conditions for women teachers. In the 1918 general election she stood in Chelsea with the backing of her union. She was not elected. None of the women who had campaigned for the vote, not even leading suffragette Christabel Pankhurst nor suffragist Millicent Fawcett, were elected. Only one of the 17 women who stood, Countess Constance Markiewicz, was elected in Dublin St Patrick’s along with 72 other Sinn Fein candidates. She was in prison for offences connected with ante conscription activities so could not take her seat. Indeed, in keeping with Sinn Fein representatives to this day, she did not do so when she was released.

The election of Nancy Astor

So it was that in 1919 the first woman to take her seat was elected in a by-election in the seat of Plymouth Sutton. When her husband inherited a seat in the House of Lords, Plymouth women petitioned Lady Astor to stand in the seat he had held in the House of Commons. Their expectations of her when she took her seat were as sky high as the rest of the country’s women. Nancy had never been part of the suffrage movement, and that was a disappointment to some, but she had plenty of relevant life experience to bring to the table and very quickly and willingly took on the role of ‘The MP for Women’. On the day after Nancy was elected, she travelled by train to her home at Cliveden. On changing trains at Paddington, she was greeted by a crowd of suffragettes, some of whom had been force fed on hunger-strike. They rushed forward and presented her with a badge saying “It is the beginning of our era. I am glad I have suffered for this.” She came to receive 2-3000 letters a week and what women raised with her was reflected in the things she supported in her work in parliament. People in Plymouth voted Nancy in at seven elections. She was their MP for twenty-six years until 1945. Well connected, self-confident, she was particularly good at dealing with hecklers in and out of parliament with wit and charm. Part of her legacy was to establish a strong, hardworking, and very positive role model for what people could expect from future female MP’s – on which Plymouth has something of a unique record. As at the date of the centenary of her by-election there had been a woman MP in one of the Plymouth seats for all but six of the 100 years since Nancy took her seat.

Lucy Middleton MP on onwards

Labour’s Lucy Middleton succeeded Lady Astor. She was selected in 1936 at a time when she could not have had great hopes of winning the seat, with Nancy very well established and popular. However, the outbreak of war in 1939 meant there was not an election until 1945. Nancy did not stand in that election and Lucy became the first Labour woman to represent a Plymouth seat, elected along with 23 other women in the 1945 landslide election.

Before that there had only ever been 39 women elected since 1918, during a time when over 2000 men were elected. Born to parents with agricultural roots Lucy had become a teacher, working all over the Westcountry. Labour was just achieving its first MP’s when she joined the party in 1916. In parliament she argued for the party to set up a committee of MP’s to represent the interests of people living in blitzed areas and the difficulties which they and their communities experienced in getting war damage claims dealt with. She lost her seat in the 1951 election to one of Nancy’s sons Jakie Astor. Middleton stood again at the 1956 election but was not elected. She lived into her 80’s playing a key role with others in recording Labour’s history and editing a book on the role of women in the movement. She had been a founding director of No More War in the 1920’s and became the foundation chair of War on Want from 1958-1968.

Dame Joan Vickers won the Devonport Seat in 1955. She had a background in welfare work with the Red Cross during the war years, seeing service in Asia and other parts of the world. She addressed numerous women’s issues, and also spoke on defence, as yet unusual in a parliament with still only 24 women members. She spoke often on Commonwealth issues and was a UK delegate to the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, and the Western European Union from 1967-74. Vickers was ahead of her time in championing the cause of trafficked people, a problem which has sadly come back to the fore as people gather together to deal with modern slavery. Dame Joan held the seat until 1974 after which she served in the House of Lords for over a decade.

In 1974 the electors of Plymouth Drake, which included a part of what had been Plymouth Sutton, elected Dame Janet Fookes. She represented them until 1997 achieving the distinction of becoming Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons from 1992-1997. During her back-bench years she too spoke on issues relating to defence, education (she had been a teacher) and matters affecting women and families. She successfully put forward a private members bill which became the 1985 Sexual Offences Act. This addressed kerb crawling, the persistent soliciting of women and increasing the maximum sentence for attempted rape. Dame Janet retired in 1997 and has since served in the House of Lords.

Work brought me to Plymouth in 1979. After standing for Devon and East Plymouth in the 1994 European election, in 1995 I had the great fortune to be selected to fight the Plymouth Sutton seat and was elected as a Labour and Co-operative MP at the landslide 1997 general election. In 1997 more women MPs were elected (120 including 101 on our side of the house), than had been elected in the 89 years since 1918. Parliament gave me the platform to fight for our new medical and dental schools for Plymouth, to stand up for investment in our world class marine science and technology sector and to ensure that their expertise could be fed into our law making processes especially during the passage of the marine and Coastal Access Bill and the Climate change Bill both of which I worked on. It is always a big part of the job to ensure the city gets its fair share of funding. This took up much energy during the three terms I was fortunate to serve while Labour was in government. In my last term I served on the Defence Select Committee and became Assistant Minister for the South West during the period following the 2008 financial crash.

An interest in defence goes with representing Plymouth in parliament. From Lady Astor through to Alison Seabeck (now Raynsford), who was elected the city’s sixth female MP in 2005, we have all played our part standing up for the military communities which form such a significant part of our Plymouth’s life. In 2005 for the first time Plymouth had two serving women MPs. Alison became a government whip in 2007 and spoke with special expertise on housing and local government. She chaired the South West Regional Committee and served as a shadow housing and shadow defence minister after Labour went into opposition in 2010. Following the loss of the Moorview seat she continues to work in support of MP’s at Westminster and to mentor many of Labour’s new generation of women MP’s

The Centenary Action Group

Plymouth has a track record second to none of sending women to parliament. I hope we have helped to kick away some of the stumbling blocks for women’s participation in politics and public life more generally. Although much has been achieved there is still so much more to press for and to safeguard.

Inspired by the suffragists and suffragettes the Centenary Action Group was set up in 2018. Bringing together over 100 activists, politicians, and organisations from across the UK it seeks to ensure that we keep up the public profile achieved nationally and locally by #Vote100. It champions the need to go further in achieving diversity of women’s parliamentary representation. It is active in putting forward the interests of women on the Covid-19 agenda. In these most peculiar and democratically challenging of times the Centenary Action Group is a welcome focal point for us to find new ways to advance women’s voice and place in parliament.

You can find out more about Linda, her work and research at her brand new website and blog Into Thin Air .