Nancy Astor was Britain’s first elected woman to take her seat in Parliament. In a political career that spanned over thirty years, Astor recognised her position as the first female in the House of Commons and aspired to be an MP for all women. On the 24th February 1920, Astor delivered her maiden speech, her first contribution to parliament, alone to an audience filled with men. Her written (and often spoken) contributions to British politics demonstrate how a politician’s personal convictions influenced their alignment with party ideologies.

Astor’s speech began by detailing her unique situation as the first woman to sit in the House:

“I shall not begin by craving the indulgence of the House. I am only too conscious of the indulgence and the courtesy of the House. I know that it was very difficult for some hon. Members to receive the first lady M.P. into the House.”

With partial franchise having been granted in 1918, Astor’s election to the Commons had been due to votes cast by the working-class men of Plymouth Sutton. Sailors and soldiers, this was a community that had suffered material and emotional losses in the Great War and was struggling to recover in the economic downturn that had followed. As a wife and mother, Astor’s position as a woman put her in a sympathetic position to recognise the issues that directly affected her female constituents and used this tactfully to convince her enfranchised constituents that she would represent all, whether they could vote or not. Although initially put forward by her husband, Viscount Waldorf Astor, to essentially ‘hold’ the seat whilst he tried to exit from the House of Lords, Astor went on to have an undefeated political career, resigning in 1945.

Establishing herself in the Commons would prove to be an almighty task, as the majority of male MPs did not approve of women serving as representatives in the Commons. These attitudes stemmed from remaining Victorian middle-class ideals about the supposed proper place for women, and a lingering distrust of politically motivated women who had participated in civil disobedience and militant activities prior to 1918. The Commons proved to be an inhospitable place for female MPs, who were forced to share cramped offices and exclusion from male-only clubs and societies, where alliances were formed, and ideas hammered out away from the influence of party whips. The very environment Astor would have encountered was not designed for women, making her foray into politics even more difficult.

A maiden speech is traditionally used to establish an Hon. Member within the chamber, and often details causes they are particularly attached to, as well as their ambitions for their parliamentary service. Personal politics are complicated, as they may not align to party ideologies. Many MPs are forced to make compromises on their views for the sake of promotions and popularity within their party. Astor, who soon became known for heckling, disruption, and a clear moral standpoint, seemed unafraid of addressing her personal convictions during her maiden speech.

“…I am perfectly aware that it does take a bit of courage to address the House on that vexed question, Drink… “

With her previous marriage in America being an unhappy one, alongside her religious beliefs (Christian Science), Astor’s view on recreational alcohol consumption more closely aligned with ideas of prohibition in 1920s America, rather than the pub culture that existed in Britain at the time. Astor was concerned for how drink affected families, and used her opening speech to call for reform, much to the audible displeasure of male MPs. To include this topic in her maiden speech was certainly controversial but it shows her commitment not only to her moral standpoint, but to women, who suffered the effects of drunkenness, often in the form of marital violence.

“I do not think the country is really ripe for prohibition, but I am certain it is ripe for drastic drink reforms.”

As an American, it is unsurprising that Astor was familiar with prohibition, but what is interesting is how she used her first speech as an MP to plead for reform on an issue that was so heavily intertwined with British culture. As expected, sitting MPs that day were not supportive of her statements, some of which subconsciously implied that the country was a nation of drunks. Reading between the lines, Astor was calling for reform on an issue that she believed that male MPs did not care about, and that is directly intertwined with her gendered experience. Much of women’s life writing draws from the experience of being female, expressed through moral and religious outlooks, so Astor’s roles of wife, mother and MP all contribute to her focus on alcoholism, despite the backlash that was to be expected from a male audience.

In her contributions to parliamentary debates and committees, it is easy to trace Astor’s priorities. Although a Conservative member, she regularly worked across-party boundaries, allying herself with other female MPs, such as Margaret Wintringham (Liberal) and Ellen Wilkinson (Labour). Banished from senior Cabinet positions in the 1920s, these female MPs acted as a collective force to push for reform in areas surrounding pensions, children and later, family allowances. Despite being pushed out of policies of economy or foreign policy, these MPs championed so called ‘women’s issues’ during their time in office.

For Astor’s maiden speech, despite the angry reception to questions of drink, the female MP pushed on to remind the House of an important fact:

“I know what I am talking about, and you must remember that women have got a vote now and we mean to use it, and use it wisely, not for the benefit of any section of society, but for the benefit of the whole.”

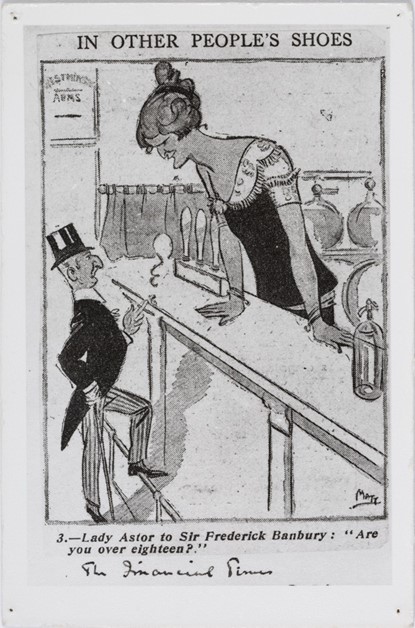

This statement set the tone for the rest of her service in the House, especially on questions of the vote. Astor remained a staunch supporter of equal franchise, supporting bills that entered the House, as well as acting as a conduit for the Women’s Movement that campaigned outside the walls of Parliament. In terms of Astor’s views on alcohol, there was no prohibition, but the Intoxicating Liquor (Sale to Persons Under Eighteen) Act 1923 made it illegal for those under eighteen years of age to drink alcohol in licensed establishments, the first successful private members’ bill from a woman MP. This law exists to this day and remains an important aspect of her political legacy.

Astor’s political career left behind an immense collection of her writing, which is held today at the University of Reading’s Special Collections. Much of this was used in the Astor100 project, which crowdfunded a statue of Astor and provided a series of public history events to celebrate the centenary of Astor’s success in the 1919 by-election. Astor’s writings in her political appointment are an important record of a female pioneer in politics, her maiden speech being just the foundation of her entry into a male-dominated political environment.

Abbie Tibbott is a PhD Student in History, researching conservatism, citizenship and democracy in 1920s Britain, with a focus on women and unemployment. She is interested in Conservative Party attitudes to those in receipt of Poor Law relief, and is undertaking research with the Cabinet Papers, held at the National Archives.

Further Reading:

To find out more about Astor 100: https://research.reading.ac.uk/astor100/

To find out more about Nancy Astor: https://olh.openlibhums.org/collections/414/