2019 marked the centenary of Nancy Astor’s entry into Parliament, leaving a fascinating legacy for women today. The National Archives plays host to a variety of documents that illuminate this moment in history. In this post, first published by the National Archives, Rachel Newton describes the significance of these documents in charting the history of this remarkable woman.

In 1918 the Representation of the People Act granted the vote to some women over the age of 30 and working class men over 21. This was thanks to the militant and non-militant suffrage campaign; a politically-driven movement that used peaceful methods, as well as militant acts of arson and hunger strikes to gain Parliament’s attention. Although this did not represent equal democratic rights between men and women, for the first time in British history, women could have an influence within Parliament, through the advent of the vote.

However, it is important to stress the importance of a different and often overshadowed piece of legislation: the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, which allowed women over the age of 21 to stand for election. This was a small act, just 26 words long, but its impact was immense. It opened the door for women’s voices to finally be heard in the House of Commons and allowed women to have a full and equal part in the polity.

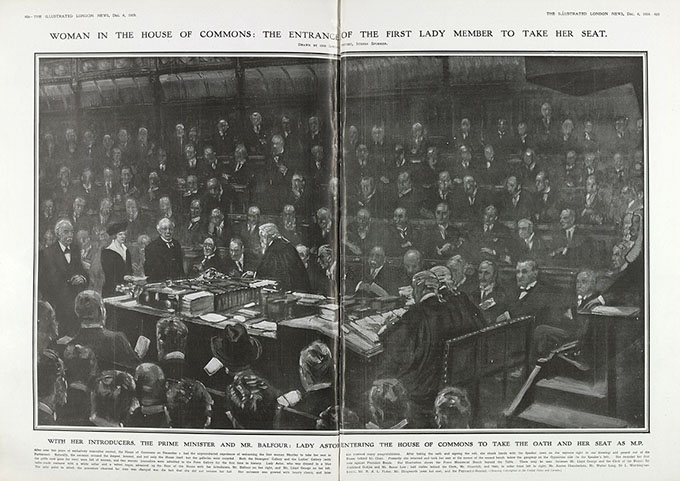

It is important to state that Constance Markievicz was the first woman to be elected as a Member of Parliament. However, as a member of the Sinn Féin party, she did not take her seat. Interestingly, she was also in Holloway Prison at the time of her election! None of the women who stood as candidates in the 1918 elections made it to Parliament, but there was a need for a woman representative in the House. The 1919 by-election provided a second chance. Thus the first voice to be heard in the House of Commons was to be Nancy Astor’s, challenging the traditional male rhetoric in Parliament forever.

Surprisingly, Nancy Astor was an American, born in Virginia in 1879. Her husband, Waldorf Astor, was the sitting MP for Plymouth from 1910 to 1919, until he was elevated to a hereditary peerage in the House of Lords following the death of his father, William Waldorf Astor. Nancy was then persuaded to stand for the seat.

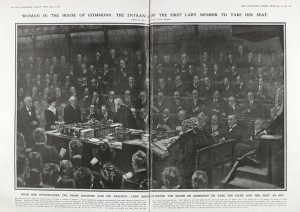

Plymouth was a constituency that she was very familiar with and the electorate knew her very well. Nancy made use of this popularity and experience within the constituency throughout her campaign, claiming she, ‘knew the real Plymouth, its children and women and its social problems better than any other candidate’ 1.

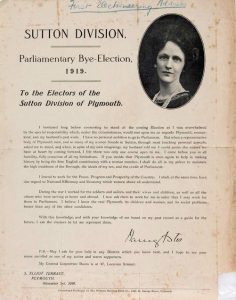

The election leaflet above highlights her confidence in her familiarity with the constituents of Plymouth Sutton and the issues that they had, especially following the ‘personal appeals’ sent to her asking her to stand. An example of the personal appeal sent to her can be seen below, whereby the ‘Woman Voters’ of the ‘Sutton division’ pledge their support for Nancy in the upcoming election. Current ‘Ask Her to Stand’ campaigns encourage more women to stand for Parliament – this is an early equivalent. We think that this was the first #askherstand moment…

Nancy was dedicated to improving the conditions in Plymouth prior to her election, establishing maternity centres and creches in the poorer parts of town. This charitable work would have appealed to the Plymouth Sutton constituents, who saw improved conditions as a result of MP’s wife Nancy’s ‘considerable record of community and national services’. Millicent Fawcett (suffragist and leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies) wrote:

‘Before she ever had the idea of entering Parliament, she took an active interest in improving the conditions of working people’ 2.

Nancy’s campaign was lively and enthusiastic. She threw herself into public speaking and engaging with her constituents on the terms that suited them. Nancy scheduled women’s meetings in Plymouth ‘for every weekday afternoon until polling day’, holding them at times that were convenient and suitable for mothers and wives.

Her cheeky American manner seeped into her campaign, with charming anecdotes or more commonly termed ‘Astorisms’ being reported in local and national newspapers. A newspaper article titled ‘Lady Astor Silences Hecklers’ describes an interaction between Nancy and the crowd:

This type of informal interaction by a viscountess, and the courageous confidence to take on adversaries, invigorated the admiration felt by constituents in Plymouth Sutton.

On 28 November 1919, Nancy won the by-election in Plymouth Sutton by more votes than her opposition combined. The document below shows the official paperwork from the by-election showing the transition from Waldorf to Nancy. Interestingly, the language used in this document, still used male terms – ‘that you do cause the name of such a member when so elected whether he be present or absent’ – highlighting the male-dominated terrain she was entering.

Despite this, Nancy was heading to Parliament to be the first female voice heard in the House of Commons, able to challenge that traditional male perspective.

Nancy served as a reminder of the female electorate and felt a duty to represent women. She would receive between 2–3,000 letters each week from women across the country asking for help. Nancy dedicated her time to women-centred politics, introducing reforms to change the status of women and children.

Working in a male-dominated environment of Parliament, Nancy knew camaraderie and cross party co-operation was the only way that female MPs could get acts passed. She was driven by her commitment to women and by the contents of her post box, rather than her political ideology. She held parties at her property, Cliveden House, and St. James Square (London), which facilitated meetings between women’s organisations and influential male MPs, allowing for the first time a direct route in which women could interact with important, high up figures within government to lobby their issues.

Throughout the 1920s, Nancy campaigned for equal franchise and other women’s issues, working closely with other female MPs such as Margaret Wintringham and Ellen Wilkinson, to force political parties to address women in the political sphere.

Nancy was a pioneer and her election changed British democracy forever. For the first time a woman was able to directly influence the parliamentary debate and the writing of the laws of their own land. Nancy was the only female MP for two years and faced a barrage of misogyny from the majority of male MPs who did not want her there. Through reliance she paved the way for female MPs to join her.

Nancy won seven elections between 1919 and 1935, eventually retiring from Parliament in 1945.

Astor 100

The Astor 100 Project, managed by Dr Jacqui Turner and a team of postgraduate students from the History Department at the University of Reading, is celebrating the election of Britain’s first sitting female MP, Nancy Astor.

Astor 100 marks a distinct change in the celebration of parliamentary history that finally and prominently shines light on female MPs and their significant contributions.

Bibliography

The National Archives, London:

- C 65/6394: c 46-61 the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, 1918

- C 219/285: Part 2, section 9: by-elections; date of election: 1919 Feb-1922 Oct

- ZPER 34/155: Illustrated London News, July to December 1919

Nancy Astor Papers, Special Collections, University of Reading:

- ‘AN HISTORIC EVENT – MRS HENRY FAWCETT ON THE ADVENT OF A WOMAN MP.’, Daily Graphic, 29/11/1919, MS1416/1/7/33, Nancy Astor Papers, Special Collections, University of Reading

- ‘Lady Astor Silences Hecklers’, Evening Transcript, 05/11/1919, MS1416/1/7/1, Nancy Astor Papers, Special Collections, University of Reading

- Nancy Astor Election leaflet, 1919, MS1416/1/1/1730, Nancy Astor Papers, Special Collections, University of Reading

- Petition from the ‘Woman Voters’ of the ‘Sutton Division’, MS1416/1/1/1730, Nancy Astor Papers, Special Collections, University of Reading

Rachel Newton is a postgraduate history student at the University of Reading, researching Nancy Astor and her achievements. She is the impact officer and digital planning contributor for the Astor100 project. This has included curating the digital Twitter exhibition, ‘An Unconventional MP: The political career of Nancy Astor in 50 documents’. Her manuscript-based research of the Astor Papers, held at Special Collections at the University of Reading, sparked her interest in the topic that resulted in her staying on to complete her MA in history.