One hundred years ago today, on 24 February 1919, Nancy Astor became the first woman to speak in the house of Commons. Here, Professor Rowbotham, an independent scholar and Visiting Research Fellow at Plymouth University, highlights the significance of the speech in championing issues relevant to the women and children of Plymouth and beyond.

Describing Nancy Astor’s maiden speech, the historian and Liberal MP Herbert Fisher told the Commons that her maiden speech was one ‘brilliant and vivid eloquence’. He added that he felt it appropriate that ‘the first speech delivered in this historic assembly by a woman should have been delivered upon a topic in which the interests of women are so closely involved’. The Commons debate was on whether or not there should be a relaxation of the restrictions imposed on the alcohol trade during the Great War. The motion was brought before a nearly full House, so over 500 MPs were there to hear Nancy Astor oppose the move of a fellow Unionist MP, Sir John David Rees (Nottingham East). Rees claimed that the current controls were ‘vexatious and unnecessary’.

Lady Astor rose to her feet to argue that they were neither. Throughout, Plymouth and her knowledge of the impact of an unrestricted liquor trade there, were at the forefront of her eloquence. All those who heard her agreed that she spoke passionately and well, even if they disagreed with her stance. It was, unequivocally, a landmark moment in national – and in Plymouth – history. She made a two-fold plea for the continuation of existing controls (while rejecting the Prohibition policy of her country of origin, the USA). It was, she claimed, a matter of national efficiency – that was why the restrictions had been brought in, at the urging of the Admiralty and War Office – and the impact on national efficiency had been dramatic. It was also a question of the moral responsibility of the state to consider the welfare of the community. Her role in the debate, she insisted, was to give voice not just to the women of her own constituency but also to the thousands of women across the country who now had the vote: she was, she believed, speaking for the ‘hundreds of women throughout the country who cannot speak for themselves’ (almost certainly a reference to the restricted franchise for women, which she strongly disapproved of). She challenged her fellows in the Chamber to accept that MPs had ‘no right to think of this question in terms of our appetite, and we have to think of it in something bigger than that’ and that meant considering the positive effect of the existing restrictions on women and families.

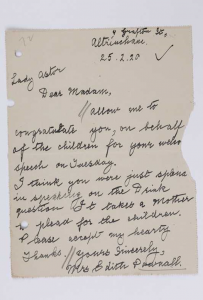

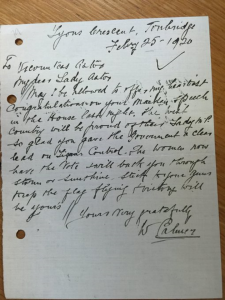

After the speech, Nancy was, in her own words, ‘snowed under’ by congratulatory telegrams and letters. Many were from women who were her own constituents, and working women elsewhere, and these, she said, gave her the greatest pleasure because they let her know that ‘the women of England’ now felt that they ‘had a spokeswoman who would press their case in the House of Commons’.

Speaking with charm, vivacity and conviction

The extensive national newspaper reportage spoke of her charm, her vivacity, her audibility and conviction – but several mentioned also her ‘strong American accent’. Despite the generally positive coverage, there was a critical undertone to several of the journalists’ comments. Some correspondents made reference to her ‘confidence’ and lack of nervousness, and her ‘dictatorial pertness’ in insisting she knew what she was talking about, implying a lack of appropriate femininity. But the local press was clearly proud of its new Member, and of the attention it gave to Plymouth. It justified the voters in electing her, and the reporters of the Evening Herald and Western Morning News had no doubt of her femininity. They concluded that ‘no maiden speech has ever been more successful’ because ‘It was not the sentiments nor the phrases they applauded. It was the courage of the lady who bearded the lords of creation in their most exclusive resort’.

One hundred years on, when you read her speech, Nancy Astor’s courage still shines brightly as does her commitment to the welfare of Plymouth and her constituents. It remains inspirational, both in terms of her words, and the context in which this maiden speech from the first woman MP to take her seat was delivered. It was then, and remains now, truly a landmark moment – as enterprising in its way as any other great voyage of discovery launched from Plymouth, and Nancy deserves to be part of the Plymouth Pantheon of Pioneers.

Professor Rowbotham is an independent scholar and Visiting Research Fellow at Plymouth University, as well as a Director of SOLON: Promoting Interdisciplinary Studies in Law, Crime and History. She is also a Royal Society of Arts Fellow, Royal Historical Society.