The installation of a statue commemorating Nancy Astor, the first woman to take her seat in the UK Parliament moved a step closer this week when a designer was chosen to create it. We are pleased to announce that Hayley Gibbs has been chosen as the sculptor. Hayley is a young artist who took the brief for the statue to heart. ‘This I Believe’ was inspired by Astor’s ‘courage and tenacity’ and will be erected outside her former family home in Plymouth later this year to mark the 100th anniversary of Lady Astor’s election as MP for Plymouth Sutton on 28th November 1919.

Nobody really knows how many statues of women there are in the UK. It is even more difficult to know what type of women they represent, invariably they are divided between royals, religious icons and, well, everyone else.

Nobody really knows how many statues of women there are in the UK. It is even more difficult to know what type of women they represent, invariably they are divided between royals, religious icons and, well, everyone else.

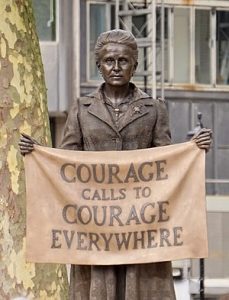

The centenary of the women’s partial vote in 2018 went part way to highlighting and addressing the issue of the lack of female statues but it has been a painful process to generate funds for pieces of public art. Statues of suffragists and suffragettes have been installed including Millicent Fawcett in Westminster Square and Emmeline Pankhurst in Manchester.

Raising money for the first woman to take her seat in Parliament was even tougher because unlike all of the others she was a politician. Astor was a Conservative MP in-between 1919-1945. Inevitably, this added the veneer of party politics to the complexity of representing a woman whose political career spanned 26 years between two World Wars.

The campaign to raise a statue to Astor was announced by Luke Pollard, MP for Astor’s Plymouth Sutton constituency. The crowdfunder and delivery of the statue was managed though an inspirational and energetic campaign led by Alexis Bowater and the Plymouth Women in Business Community Network. Support for the crowdfunder was cross party, it was backed by Prime Minister Theresa May and prominent female politicians, past and present, including Betty Boothroyd and Harriet Harman. That said, it has not been without its controversies within the local politics of Plymouth, with different parties and individuals with differing opinions, concerning what the statue represents. The Astor statue is not alone, in February this year, London rejected a statue of Margaret Thatcher for fear it would be vandalised and only after some debate was it agreed that the statue would instead be erected in her home town of Grantham. Meanwhile statues of controversial men, misogynists, racists and those with anti LGBTQ credentials become part of the landscape with little comment.

The money was raised in Plymouth by Alexis Bowater and the Plymouth Women in Business Network Community Interest Company in a campaign that in many ways reflected Nancy Astor’s own campaign for election in 1919. Astor appealed to the people of Plymouth to send the first woman to parliament and now Alexis and the committee appealed again to erect the first outdoor, public statue of a female MP.

Astor herself is a controversial figure. While her often unguarded statements and political views are not untypical of her time, they are less appealing to C21st donors. Arguably, her greatest political challenge was accusations of hosting the ’Cliveden Set’, a group of alleged pro-German appeasers who were believed to hold too much political sway outside of Parliament. Despite the discrediting of the existence of a ‘Set’ the appeasement slur persists. Allegations of anti-Semitism often came from unguarded statements that did not reflect her support of individuals in private; however, she was pilloried in a way that many powerful men expressing more overt views were not. Astor won seven elections between 1919 and 1945. She retired from parliament in 1945 yet despite the longevity of career, her legacy has been dogged by half-truths and untruths that have become legend. Another legacy of her gender – we judge women by higher standards.

Nancy Astor never wrote an autobiography or asked for a statue – she asked that her memorial was litter bins across Plymouth to ‘keep the city clean’. However, this statue represents an important milestone in our democracy. The statue might well be the first public statue of a woman MP outdoors and accessible to all people and as such the legacy of this project is clear. In 1919 Nancy Astor’s voice was loud and unafraid – we remember her because hers was the first female voice to echo around the chamber of the House of Commons. We hope that her statue, another first and fittingly for the first to a woman MP, will again be a loudspeaker, this time for young women and girls, encouraging them to engage and be heard.