We are delighted to post a LONG READ by Robin Harragin Hussey on a much overlooked but fundamental influence on the life of Nancy Astor – her adherence to Christian Science . Any collection on Astor would be incomplete without an exploration of her faith.

Robin studied Religious Studies at Sussex University and gained a Masters and PGCE from Kings College, London. A lifelong Christian Scientist, she has worked to present religion to her students and in a wider arena as a medium through which change for good and healing can be effected. Most recently she was appointed Christian Science Committee on Publication, London and District Manager of the Committees on Publication in UK and Ireland. This position involves liaising with the media and legislature on issues to do with Christian Science.

Nancy Astor was an American southern belle who married into one of the wealthiest families in England. She joined the Church of Christ, Scientist, five years before becoming the first woman to sit in the House of Commons in 1919. Did this new-found faith have an impact on her political life? Arguably, yes, in that it most certainly had a profound impact on her personally. Both her husband, Waldorf Astor, and one of her best friends, Phillip Kerr, later Lord Lothian, were committed Christian Scientists and both worked in government at a high level. The Church itself was flourishing in Britain, and the Astors, along with Lord Lothian, became founding members of a new Christian Science branch church – Ninth Church of Christ, Scientist, London. This large, purpose-built church on Marsham Street, was just minutes away from the Houses of Parliament. Indeed, there was even a bell in the church which rang to signal Divisions in the House of Commons.

University of Reading, Special Collections, Nancy Astor Papers

Christian Science was brought to Britain from America in the late 19th century. The new Christian denomination had been established by Mary Baker Eddy in New England. It was through her lifelong study of the Bible that Eddy found herself healed of both the illnesses that plagued her for years and of the effects of a near fatal accident. This life experience — an earnest search for health and most centrally her further research of the Bible — led her to discover how the teachings and healings of Jesus Christ could be made practical in a system of prayer-based healing, which she later named Christian Science. It was Eddy’s book Science and Health with the Key to the Scriptures that Nancy Astor read, and which had a profound effect on her life.

No stranger to religion, as a girl Nancy read the Bible and attended St Paul’s Episcopal Church in Charlottesville near her home in Virginia. The young priest here, Reverend Frederick W. Neve, made a strong impression on her and became a lifelong friend and confidant. He introduced her to both the Sheltering Arms, a home for the indigent, and his missionary work among the poverty-stricken inhabitants of the Blue Mountains. Later she wrote: ‘I don’t think I had realised before how many poor and unwanted people there were in the world.’[i]

While she learned of the good works of the church through Reverend Neve, it was through reading Eddy’s book that she learned how Christianity could lead to healing. She was first healed of painful abscesses and, later, other debilitating illnesses which she had suffered from throughout the early part of her marriage to Waldorf. Recalling that first healing, she later wrote: ‘I can never forget that first flash into my consciousness that God made neither sin nor sickness, that God created only good, and man in His image and likeness.’[ii] Thereafter, she became a lifelong student of Christian Science and, as biographer Adrian Fort was to subsequently state: ‘She regained her health and vigour and remained in good health for the rest of her life.’[iii]

Christian Scientists are called ‘students’ of their faith because they study it regularly, not just to understand more of God and His love for His creation, but to make it a way of life. They read a daily Bible lesson, ponder the Scriptures and the writings of Mary Baker Eddy and often go to church twice a week. Nancy was such a student. Fort noted:

Her friends sometimes used to ask why she spent so much time with the book, to which her reply was usually, “It means everything to me: it’s how I run my life, you know.”[iv]

This was not just a private faith for Astor – she willingly shared it with others, as some of her detractors have all too readily pointed out. Yet, rather than proselytising, Astor had a genuine sense of love for those in need and a desire to help. Indeed, several letters she received reveal that she helped many people both spiritually and practically. One such person was Florence Brain who wrote:

It wasn’t a small thing, I assure you, & I cannot say how grateful I am for the consecrated work you did. Do, for the world’s sake – take the practice [of Christian Science] which comes to you, & please let me know what I owe.[v]

The reference to payment here is simply explained. Mrs Brain regarded Astor as akin to a Christian Science practitioner, whose healing work is not only their full-time occupation but their only source of income. It is unlikely Astor would have taken payment, but this desire to remunerate shows the woman’s gratitude to Astor. Another biographer, Christopher Sykes, tells how Astor paid the gambling debts of a young friend. While she had the money, this wasn’t just the case of easy generosity, but is indicative of her compassion for her fellow man/woman. She later paid off this friend’s debts again, not, as some might say, because she was naive, but because of her capacity for forgiveness.[vi]

It was perhaps inevitable, therefore, that her full and active religious life should spill over into her political one. In fact, it can be convincingly argued that her religious convictions underpinned many of her actions and decisions. It certainly gave her the spiritual support she needed. From the moment she stepped into the House of Commons, and throughout her time there, it is well documented that she was received not only with great suspicion but actual aggression. She later wrote:

When I stood up and asked questions affecting women and children, social and moral questions, I used to be shouted at for five or 10 minutes at a time. That was when they thought that I was rather a freak, a voice crying in the wilderness.[vii]

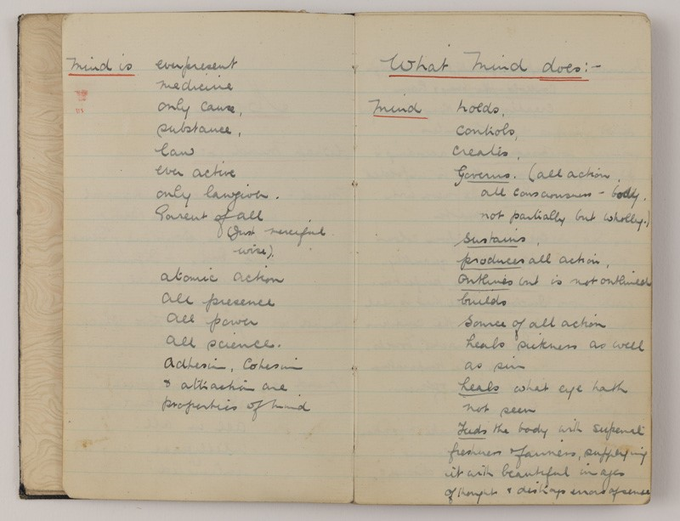

It explains many of her handwritten notes, aide-mémoires, notebooks, and annotations on typewritten articles. They included such headings as, ‘The necessity for handling evil’, ‘Aggression’ and ‘Love’.[viii] They show she often drew on the teachings of Christian Science to help her cope and overcome these challenges. In this same collection is a letter from a Christian Scientist called Cissie Troy written in 1931. She assured Astor of God’s divine protection, quoting the Bible’s assertion that we are “hid with Christ in God” every moment, and, referencing Eddy’s statement in Science and Health, Troy wrote: ‘… we rejoice to know that you as His Witness are “clad in the panoply of Love” and kept in His wisdom. What a joy to know that you are not alone because the Father is ever with you.’[ix] This sense of being God’s witness is not untypical of a Christian’s understanding of their work in the world.

Astor’s personal journal kept in her bedside table suggests a strong correlation between her faith and her political career. University of Reading Special Collections, Nancy Astor Papers

During Astor’s early years in the House, she received a letter from Annie Knott who like her, was in some sense a female pioneer – being the first woman appointed to the Christian Science Board of Directors, the Church’s governing body in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Although women had always played an important role in the Church, ten years was still to pass after Eddy’s death before Knott’s appointment to the Board. In the letter she congratulated Astor on being the first woman to sit in the British Parliament: ‘It is so splendid that the moral and religious forces in England rallied to your support and that proved the powerlessness of prejudice to impede in any wise the establishment of God’s kingdom on earth for that is what we are really working for all this time is it not?’[x] This higher sense of mission that Knott writes about here is something that Astor was to increasingly embrace.

One of her great moral causes, something wholly in line with the teachings of Christian Science, was her fight against the excesses of alcohol. Mary Baker Eddy wrote of the high moral standards for Christian Scientists:

‘Christian Science teaches: Owe no man; be temperate; abstain from alcohol and tobacco; be honest, just, and pure; cast out evil and heal the sick; in short, Do unto others as ye would have others do to you.

Eddy, who was well aware of humanity’s struggles, continued: ‘Has one Christian Scientist yet reached the maximum of these teachings?’[xi] It was a pertinent question as Astor, like many people, was consciously trying to live her faith as best she could. In the same way you don’t judge the principle of mathematics by the abilities of mathematicians, Astor, it has to be said, was no paragon of Christian Science and certainly not, as the popular press of the day and some of her fellow MPs would have it, an American-style Prohibitionist or religious dogmatist.[xii] Indeed, although neither she nor Waldorf drank alcohol, she often served it to guests at her many parties.

Notwithstanding her religious beliefs, Astor’s divorce from her drunkard first husband, Robert Gould Shaw, was the real foundation of her loathing for alcohol. In addition, her constituency work in Plymouth showed her the dire consequences of poverty and misery that drinking can cause. It was perhaps not surprising therefore, that it was the theme of her maiden speech to the House.

It explains what was probably one of her greatest political achievements – the enactment of her private member’s bill, The Intoxicating Liquor (Sale to Persons Under Eighteen) Bill 1923, which greatly helped in the battle against underage drinking. Astor continued to work for the temperance cause and spoke at many meetings around the country. Writing to an American Christian Science friend, Sally Bell, four years later, she said: ‘I am back at work and pretty busy. I’ve been on a Temperance tour speaking at Glasgow, Louth, Grimsby and Cardiff and am down here for a fortnight with meetings every evening.’[xiii]

Another cause dear to her heart was the welfare of women and children. Astor was to recall that while navigating the hostile environment of the House in her early years as an MP, ‘I had to do what the women wanted me to do, I had to just sit there.’[xiv]

Later, commenting on the paucity of legislation protecting them, she wrote: ‘The 12 years before they [women] had the vote, there were only five measures passed dealing with women and with things affecting women and children.’[xv] But, she added, in the decade following her election to Parliament, there were no less than ten measures passed supporting them.

Her religious inspiration in championing women’s causes couldn’t have been clearer than in March 1928. During a debate on the ‘Amendment of the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Bill’, which increased the franchise to women by lowering it to the age of 21, Astor quoted the Biblical story of Zelophehad’s daughters[xvi]. It details their successful appeal to Moses which saw them inherit their father’s lands.

Although she was never directly involved in the suffrage movement, she nevertheless worked with some of its leaders and used her position as an MP to champion their causes. To this end, she used her knack to bridge class divides and bring people together for a common cause. With her husband’s wealth and political connections, his influence as the owner of The Observer newspaper, and her own broad spread of acquaintances, the Astors’ parties and gatherings at their country residence, Cliveden, and their London home in St James’s Square, attracted an eclectic mix of guests. When interviewing Astor in 1956, MP Mary Stocks, recalled their time together in the House and how the parties often proved to be a vital conduit for meeting ‘political people of importance.’[xvii]

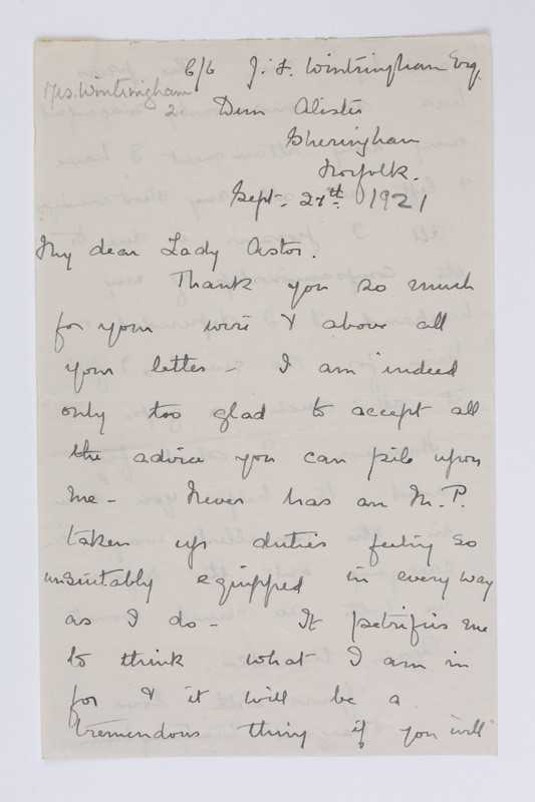

Her largely middle-class American upbringing was a major contributor to her ability to engage with all classes in Britain. But there was another significant element at play – her spiritual conviction that everyone was equal. In an unaired script for the BBC about her religious views, Astor wrote that her favourite passage in Science and Health was: ‘One infinite God, good, unifies men and nations, … annihilates … whatever is wrong in social, civil, criminal, political, and religious codes.’[xviii] Astor’s deep-rooted conviction that all were equal before God had some remarkable results. In 1924 the Astors entertained the King, along with some Labour government ministers – the first time many of them had met royalty. Her ability to navigate social divides with relative ease was again demonstrated some years later following a tour of some of South Wales’ poorest areas after the 1926 General Strike. Accompanied by fellow Christian Scientist and MP, Margaret Wintringham, Astor and her husband entertained both employers and union leaders at St James’s Square in a bid to bridge the bitter divide between the two sides.[xix]

Friendship letter from Margaret Wintringham who joined Astor as the 2nd female MP in 1922. The two formed a close bond during their time in the House together, despite being in different parties. They both also bonded over their common faith. University of Reading, Nancy Astor Papers

While these and many similar cross-class events owed much to Astor’s informality, energy, charm, and razor-sharp repartee, the latter sometimes got her into trouble – not least her well documented and colourful clashes with Winston Churchill. She earned a reputation for ill-advised outspokenness, resulting in accusations of anti-Semitism and of being anti-Roman Catholicism. She was, nevertheless, a woman of her time, when perceived prejudice was not uncommon. But for Astor these were not considered opinions, simply ill-thought-out, off-the-cuff generalisations. In fact, she had a number of Jewish and Catholic friends and usually got on well with people whatever their faith. For example, she was great friends with Labour MP and Methodist, Ellen Wilkinson, and nursery school founder, Margaret Macmillan, who was interested in dreams and mysticism.[xx]

If Astor caused headlines with some of her controversial opinions, the fact she was a Christian Scientist also generated no small amount of anathema. One of the attacks particularly upset her, coming as it did from friend and Liberal MP, H. A. L. Fisher, who had been a frequent visitor to some of the Astors’ homes over the years. Fisher, the Warden at New College Oxford, where two of the Astors’ sons studied during his tenure, dealt the couple and, indeed, Christian Scientists in general, an unwelcome broadside with the publication of a 1929 polemic entitled Our New Religion which bitterly criticised the religious movement. The views he expressed, which attracted considerable publicity, were, however, completely unrecognisable by Christian Scientists themselves. Despite efforts by both the Church and individual members to counter Fisher’s assertions, only a handful of newspapers – including The Observer and Saturday Review – published any corrective responses.

A few years later, in the lead up to the Second World War, the Astors were caught up in the so-called ‘Cliveden Set’ controversy. She and many others had been fighting hard to keep Britain out of the war, a legitimate and widespread Christian position inspired by the many New Testament teachings on peace. But quite wrongly, they were accused of trying to force a policy of appeasement on the government. Although this has since been widely discredited by a number of leading researchers, it caused huge damage to the couple’s reputation at the time and cast a significant pall over Lady Astor’s political career.

As a consequence, and after 26 years as the Conservative MP for Sutton Plymouth, Astor very reluctantly heeded the advice from her husband and others and stood down. It was a move that left her deeply disturbed and caused a rift between her and Waldorf. She asked for help, as she had done throughout her career, from a Christian Science practitioner. The healer she turned to on this occasion, Miss Evelyn Heyward, from Chelsea, wrote this to her: ‘Someone very near to our Leader (Mary Baker Eddy) has said: “Whatever the condition or circumstance, we can & must love our way out”.’ The practitioner continued:

There is only one place where you can meet this sense of strife, division, separation, and that is in your own sense of what alone is real [the presence and love of God] … Learn to see this leaving of the House as your greatest blessing ...[xxi]

But it took Astor a long time to come to terms with her departure from frontline politics. She had long been deeply caught up in the higher mission of her career, one which she had almost exclusively viewed through the lens of her faith. As with the letter from Annie Knott at the beginning of her political career, her close friend Lord Lothian epitomised what it was about her faith that motivated her in a letter written to her from aboard the US-bound Aquitania in January 1936. Musing about the relationship of politics and Christian Science, a subject frequently brought into question by some of their mutual friends, he wrote:

I see that the claim of politics and human power is one of the menaces to every [Christian] Scientist, but I also see it is one of the central functions of [Christian] Scientists and the CS [Christian Science] movement to demonstrate. God’s government of the universe inclusive of man which means better laws, the ending of war and poverty, the unity of men and nations all of which take shape as laws and constitutions as well as in more Christian humans. So it is not politics but the way we go at the problem of government that counts’[xxii]

After stepping down from her political career, which for so long had been the very purpose of her being, Astor spent the rest of her life committed to her family and church and never took public office again. However, she had left behind a legacy of pioneering strength, largely undergirded by her Christian Science, and exemplified by her courage in withstanding those often turbulent early years as the only woman and later one of the very few women in the House of Commons. Despite more than a quarter of a century of often biting aggression and whispered opposition, she never once lost her energy and nerve. She cared little for prestige and political preference. Her focus was on the causes of social change and improvement, which she saw as particularly vital for both women and children. As a result she achieved little public recognition for her work. And neither did she want it, preferring instead, as she instructed the Plymouth council, a memorial of more rubbish bins in the city!

Astor, a unique and unusual character and driven by a very strong desire to bring in God’s government, admittedly had many flaws, but flaws undeniably tempered by her humanity and unequivocal love for her fellow man.

References

BBC Radio 4, Woman’s Hour, 22 February 2002, London

Astor N., MS 1416/1/2/583, Letter to Sally Bell, University of Reading Special Collections, Nancy Astor Papers

Astor N., Christian Science Notes And Papers Re Church, University of Reading Special Collections, Nancy Astor Papers

Brain F., Nancy Astor Papers Pre 1928, Letter, University of Reading Special Collections, Nancy Astor Papers

Cracknell R., and Gay O., Women In Parliament: Making A Difference Since 1918, House of Commons Library, http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/RP13-65 accessed 1 November 2013

Eddy, Mary Baker, First Church Of Christ, Scientist, And Miscellany, The Christian Science Publishing Society, 2007, USA

Fort, A., Nancy: The Story Of Lady Astor, Vintage, 2013, London

Hansard, Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Bill.HC, Deb 29 March 1928, vol 215 cc1359-481

Hayward, E., MS 1416/1/2/583, Letter, University of Reading Special Collections, Nancy Astor Papers

Kerr (Lord Lothian), P., Letters to Nancy Astor, Blickling Hall, Lord Lothian Papers

Khuddro, Melanie, ‘That Vexed Question’: Nancy Astor’s Maiden Speech By Melanie Khuddro – Astor 100, Astor 100, https://research.reading.ac.uk/astor100/that-vexed-question-nancy-astors-maiden-speech/ accessed 26 May 2020.

Knott, A., Christian Scientists 1915-1927, Letter, University of Reading Special Collections, Nancy Astor Papers

Sykes, C., Nancy: The Life Of Lady Astor, Granada Publishing Ltd, 1979, St Albans

Troy C., Christian Scientists Notes And Papers Re Church, Letter, University of Reading Special Collections, Nancy Astor Papers

[i] Fort, Nancy: The Story Of Lady Astor, 2013, p. 32

[ii] ibid, p. 136

[iii] ibid, p. 137

[iv] ibid, p. 185

[v] Brain, Nancy Astor Papers Pre 1928, Letter

[vi] Sykes, Nancy: The Life Of Lady Astor,1979, p. 334

[vii] Cracknell et al, Women In Parliament: Making A Difference Since 1918, p. 24

[viii] Astor, CS Notes And Papers Re Church, Notes, notebooks, printed and typewritten articles etc

[ix] Troy, CS Notes And Papers Re Church, Letter

[x] Knott, Christian Scientists 1915-1927, Letter

[xi] Eddy, First Church Of Christ, Scientist, And Miscellany, p. 114

[xii] Khuddro, That Vexed Question’: Nancy Astor’s Maiden Speech By Melanie Khuddro – Astor 100‘, 2020<https://research.reading.ac.uk/astor100/that-vexed-question-nancy-astors-maiden-speech/> accessed 26 May 2020.

[xiii] Astor, MS 1416/1/2/583, Letter to Sally Bell

[xiv] Fort, Nancy: The Story Of Lady Astor, 2013, p. 180

[xv] Cracknell et al, Women In Parliament: Making A Difference Since 1918, p. 24

[xvi] Hansard, Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Bill.HC, Deb 29 March 1928, vol 215 cc1359-481

[xvii] BBC Radio 4, ‘Woman’s Hour’

[xviii] Astor, Christian Science Notes And Papers Re Church, Notes, notebooks, printed and typewritten articles etc

[xix] Fort, Nancy: The Story Of Lady Astor, 2013, pp. 215-216

[xx] Sykes, Nancy: The Life Of Lady Astor, 1979, p. 328

[xxi] Hayward, MS 1416/1/2/583, Letter

[xxii] Kerr, Blickling Hall, Letters to Nancy Astor

You can find out more about Robin’s research at The Religious Studies Project