by Laurence Talairach, CBCP Visiting Research Fellow 2024

Professor of Victorian Literature and Culture, Alexandre-Koyré Center/University of Toulouse Jean Jaurès

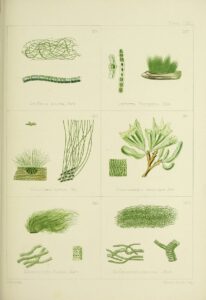

Images from British Sea-Weeds, vol 1 (1863), the Internet Archive

My current research project looks at the forms of natural historical knowledge produced by British women in the nineteenth century, at a time when they had little access to scientific institutions and remained in the shadow of a husband, father or brother. Using a wide range of textual and material archives (natural history collections), travel narratives, popular science books, fiction and visual documents (photographs, illustrations, paintings), it seeks to re-evaluate the place of nineteenth-century British women in the field of natural history on the basis of their creations, and analyse simultaneously the various media that testified to their involvement in the scientific field. As literature and the arts were, for various reasons, essential tools that opened up access to science for women, I applied for a CBCP visiting fellowship at the University of Reading in order to focus on the correspondence between Margaret Gatty (1809–1873) and Juliana Horatia Ewing (1841–1885) and their editor, George Bell (1809–1899).

The University of Reading’s Special Collections are based in the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL), a quiet and enchanting place within walking distance from the centre of Reading. As you pass through the museum on the way to the reading room, you instantly travel back in time: the Victorian building used to be a family home built in the late nineteenth century and still retains many original Arts and Crafts features, some of them designed by potter and tile designer William De Morgan (1839–1917). Working on two Victorian children’s writers, I was therefore delighted to be able to work in such an environment.

My aim was to examine Margaret Gatty’s and Juliana Horatia Ewing’s correspondence so as to see whether the children’s authors merely discussed their literary projects with their editor or shared other interests. Gatty had, indeed, a passion for marine botany; her daughter was a botanist and horticulturalist, and both women used their scientific knowledge and discoveries as sources of inspiration for their children’s books. The Bell archive contains several hundreds of letters by the Gatty family (Margaret Gatty’s, her husband’s and their children’s) to George Bell and Frederick Daldy, and I soon fell down the rabbit hole as I discovered many more letters than expected – several dozens of them highlighting Gatty’s scientific knowledge and the difficulties she encountered as a Victorian woman, struggling as she did to be considered as an expert marine botanist and not simply as a science populariser, a purveyor of scientific knowledge, interpreter or translator of scientific language.

The reason why women’s scientific expertise was generally dismissed by male naturalists throughout the nineteenth century was due to the fact that although women collected nature, presented their observations, described, illustrated and translated natural history into a simpler language for women and/or children, they lacked formal education and professional training and were hardly ever taxonomists. The natural history they practiced often remained in the domestic space and was kept safely apart from the halls of Victorian science. Even when published and circulated throughout the country, their scientific contributions have therefore often been overlooked because of their association with popular science or children’s literature, as is particularly the case of Margaret Gatty.

With the wonderful help of librarians Michelle Drisse and Emma Farmer, I was able to have access to uncatalogued letters recording the genesis of Margaret Gatty’s famous popular science work: British Sea-Weeds (1863). To my surprise, the narrative of its publication appeared much more complex than generally known. J.A. Bryant, H. Plaisier, L.M. Irvine, A. McLean, M. Jones and M.E. Spencer Jones had worked on these letters in 2016, explaining how British Sea-Weeds was first meant to be a revised synopsis to accompany The Atlas of British seaweeds, re-drawn from William Henry Harvey’s Phycologia Britannica, or, A History of British Sea-Weeds (1846–1851), a book which had spurred Gatty’s interest in marine botany.

However, the numerous exchanges of letters between Margaret Gatty and George Bell revealed as well her editor’s demands, Gatty’s fears concerning her reputation as an algologist and the way in which she successfully managed to revamp the original synopsis Bell aimed to publish so as to assert her scientific persona.

My stay at the University of Reading as a CBCP visiting research fellow was therefore very fruitful and has opened up many new ideas and opportunities which I hope to develop in the near future. I wish to thank the co-directors of the CBCP, Dr. Nicola Wilson, Dr. Sophie Heywood, Prof. Daniela La Penna and Prof. Sue Walker, for supporting this research, welcoming me to Reading and inviting me to take part in their social events, and look forward to returning to the University of Reading to carry out more work in the special collections very soon.