by Dr Buxi Duan

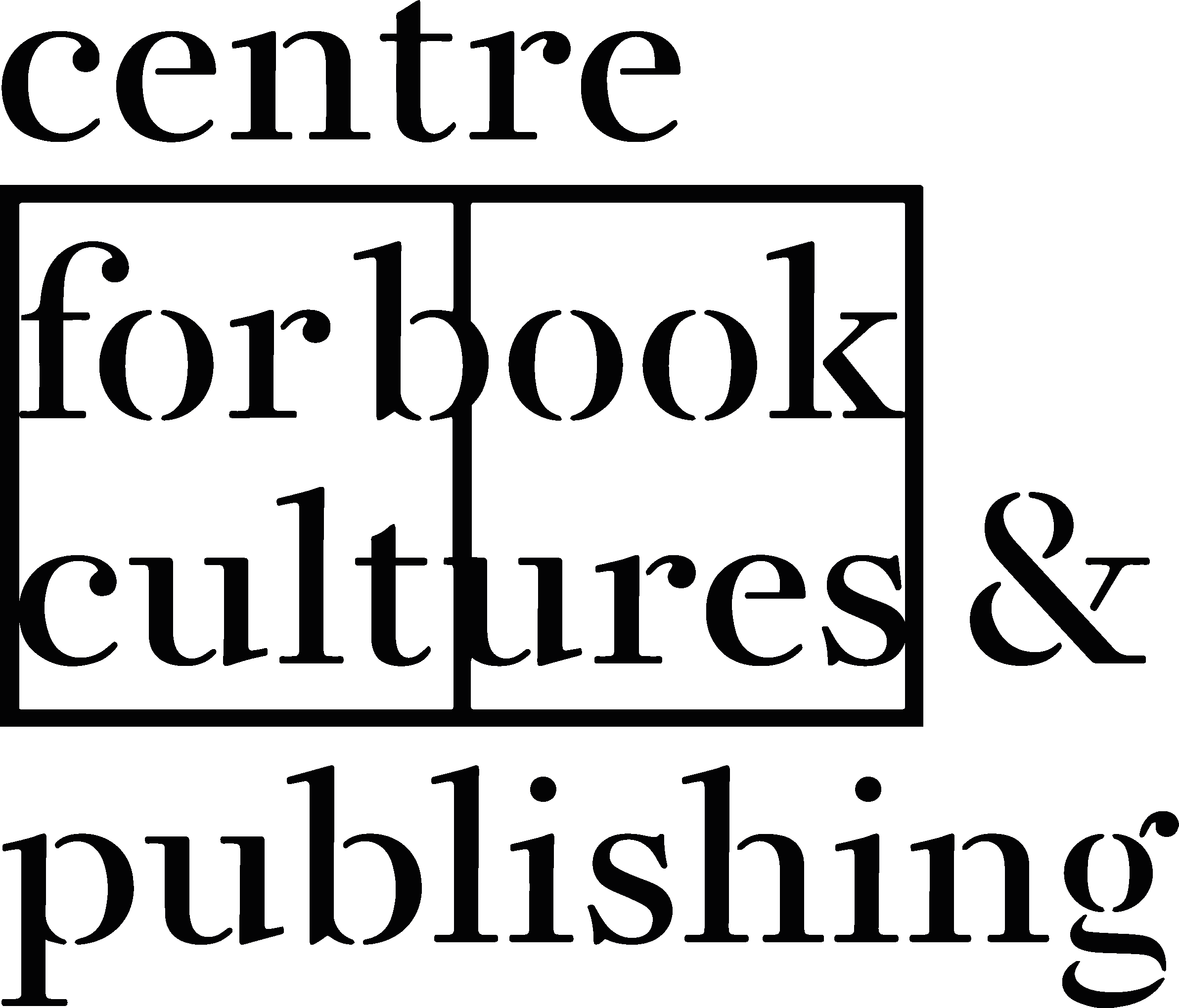

Fig 1: Typescript with handwritten annotation for

Three Guineas by Virginia Woolf from the Hogarth

Press archive. Courtesy of the Modernist Archives

Publishing Project

What does scholarly editing mean for modernist literature? How has it developed over time? And why does it matter? In other words, how does a modernist masterpiece like Ulysses or The Waste Land – texts that evolved from drafts, proofs, and countless editions – become the book we hold in our hands today?

In order to try to answer these questions, or to stir more discussion, to be more precise, we brought together leading and emerging voices in the field to explore the evolving practice of editing modernist texts – from broad theoretical perspectives on what an ‘authoritative’ edition means to detailed case studies of editing individual works – at the ‘Modernist Editing’ symposium at the University of Reading on 23 September 2025. Not surprisingly, modernist literature challenges its editors from the very texts themselves: modernist authors often left behind multiple drafts, proofs with annotations and alterations, and different editions, each reflecting a different stage in the creative revision of the work that made the modernist author known to us today. This symposium offered us a timely opportunity to immerse ourselves in, and reflect on, how these textual and material complexities shape our understanding of what a modernist text really is.

The morning session started with a presentation by Dr Chris Mourant (University of Birmingham), in which he offered a vivid case study of E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India (1924) based on his editorial work on the volume for The Cambridge Edition of the Fiction of E. M. Forster. Through meticulous comparison of handwriting and textual variants, he demonstrated how the pre-publication materials (avant-texte) – though sometimes a source of confusion – are also the key to resolving it. Building on Dr Mourant’s discussion of the many versions (drafts) of modernist literature, Dr Wim Van Mierlo (Loughborough University) then traced the development of scholarly editing theory. He reminded us that, unlike medieval or Victorian texts – often transmitted through a published edition or a limited number of extant manuscripts – modernist works tend to survive in an unprecedented abundance of drafts, proofs, and printed versions. These materials range from rough manuscripts and corrected typescripts to magazine publications and competing national editions. Such richness offers editors invaluable insight into creative fluidity, while also triggering a fundamental question: which version, among so many, should be used as the ‘authoritative’ base text? As Van Mierlo noted, the traditional Anglo-American scholarly editing framework typically addresses this question by recording all variants in a textual apparatus – the detailed record of rejected readings, normally placed at the end of the volume, that can be referred to and read in comparison with the chosen base text – a balance between scholarly rigour and commercial practicality, while inevitably disrupting the fluidity of a work in print format.

Fig2: Q&A after the presentation. Photo credit: Buxi Duan

In response to the limitations of printed editions and the desire to engage readers more directly with the creative process of modernist writing, Dr Joshua Phillips (University of Oxford) has launched The Digital ‘Anon’, a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship project presenting Virginia Woolf’s final, unfinished work in digital form. Using TEI-XML, an open standard for encoding literary texts, Phillips’s interactive website allows readers to view Woolf’s manuscript alongside a scholarly transcription for the first time. While digital editing practices using TEI-XML are not new, The Digital ‘Anon’ presents itself as an exemplar for its clarity and fidelity to Woolf’s manuscripts. By combining meticulous textual scholarship with an accessible interface, the edition invites both specialists and general readers to trace Woolf’s revisions and experience the material texture of her writing. With its minimal yet illuminating annotations, it strikes a delicate balance between scholarly rigour and public engagement, exemplifying how digital tools can present modernist textuality to a 21st-century readership.

Fig 3: Geoff Wyeth, Lecturer in Printing Technology at

the University of Reading, shows the University’s

distinctive collection of historic printing presses.

Photo credit: Buxi Duan

Between sessions, we had the privilege of enjoying a guided tour of the Historic Presses workshop – a fitting reminder that scholarly editing, like typesetting, remains a craft grounded in the material processes of making books. The afternoon panel, ‘Editorial Frameworks & Scholarly Editions’, brought together three editors leading major modernist editions. Dr Rebecca Bowler (Keele University), co-General Editor of the Edinburgh Critical Editions of the Works of May Sinclair, complemented earlier speakers’ reflections on their sweet struggle with authors’ drafts and revisions. She outlined the editorial framework guiding the Sinclair edition and the careful balance it seeks between fidelity to authorial intention and the practical demands of publication. Dr Barbara Cooke (Loughborough University), co-executive editor of the Oxford University Press Complete Works of Evelyn Waugh project, reminded us that behind every scholarly edition series are the people whose dedication and collaboration give warmth to these long-term projects. Scholarly editions are painstaking enterprises: they clarify errors introduced through a text’s transmission and dissemination, but they also depend on the sustained passion of successive generations of editors.

As Cooke aptly observed, the preparation of a scholarly edition can span decades. The Cambridge Edition of the Letters and Works of D. H. Lawrence, for example, began in the 1970s and only reached completion in 2018, with further corrections published in 2024. For each new contributor, what they joined was not simply an editing project but an ongoing (a)synchronous conversation with both the author and other editors. Professor Bryony Randall (University of Glasgow), co-General Editor of The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Virginia Woolf, offered a thought-provoking discussion of ‘non-authorial’ influences in the editorial process, focusing on Leonard Woolf’s role in shaping Virginia Woolf’s literary reputation. Her reflections invited us to reconsider the myth of the solitary genius and to recognise modernist authorship as a more networked and collaborative phenomenon – one in which editors, publishers, and other often-neglected figures participate in the shaping of literary legacy.

The day concluded with a lively roundtable that brought together scholars at different career stages to share their ongoing projects and reflections on the state of modernist editing. Professor Mark Nixon (University of Reading) and Professor Steven Matthews (University of Reading) discussed the Samuel Beckett Digital Manuscript Project; Dr Wim Van Mierlo offered perspectives on current developments in textual scholarship; and Dr Buxi Duan (University of Reading) introduced his ongoing project on a digital scholarly edition of D. H. Lawrence’s notebook. This one-day symposium created a unique space for both speakers and participants to reflect on the past, present, and future of modernist editing, and to discuss critically why it continues to matter. A potential answer, from one’s perspective as an organiser, might be that scholarly editing keeps both the texts and the processes of their evolution vividly alive.

Organised by Dr Buxi Duan and Lawrence Jones, with support from Professor Nicola Wilson and the Centre for Book Cultures and Publishing (University of Reading), the symposium was generously funded by the Samuel Beckett Research Centre (University of Reading) and a conference subvention provided by the Bibliographical Society (UK), which enabled several postgraduate and early-career researchers without institutional backing to attend the event in person.