By Dr Aleksandra Wieczorkiewicz, CBCP Visiting Research Fellow 2022–23

“The old schoolroom at No. — Eccleston Square […] wide, low room at the very top of one of the tallest houses in the square; the three broad windows faced westwards and on spring afternoons let the full glare of the sun fall in dusty squares on the faded carpet and made dazzling reflections on the gaudily-coloured pictures” – so begins The Cousins and Their Friends, by “the author of Sydney Grey etc.” (i.e. Annie Keary, children’s writer and poet), a novel which was published serially starting from the first issue of Aunt Judy’s Magazine in 1866. Let us take a moment to immerse ourselves in the atmosphere of the schoolroom, where Hugh and Ratcliffe Lord spend a warm Friday afternoon searching the dictionary for Latin verbs and nouns. Ratcliffe is engrossed in translating a passage from Aeneid, and in this not so easy task he is helped by his sister, Kathleen:

“Now listen, Kathy, and tell me if that sounds right,” Ratcliffe began. “Tum then Dido—Dido—demissa, having thrust off or cast away, breviter voltum, her short face; stay, I’m afraid those two words can’t be coaxed to go together, but at all events I know voltum is a face, so don’t bother to look for it; let’s try again. Then Dido having, in short, thrown away her face, profatur, set forth, solvite corde, with an untied or unfastened heart, metum Teucri, to meet the Teucrans.”

“Oh, but stop a minute, Ratty,” exclaimed Kathleen; “how could Dido go to meet the Teucrans, if she had thrown away her face; and, besides, can metum possibly be a verb?”

“Oh, bother! yes, to be sure it can—a disgusting supine, you may depend—‘to meet the Teucrans,’ yes, that goes very well. It is oddish about Dido’s face, certainly; but, never mind, she’s always doing something odd […].”

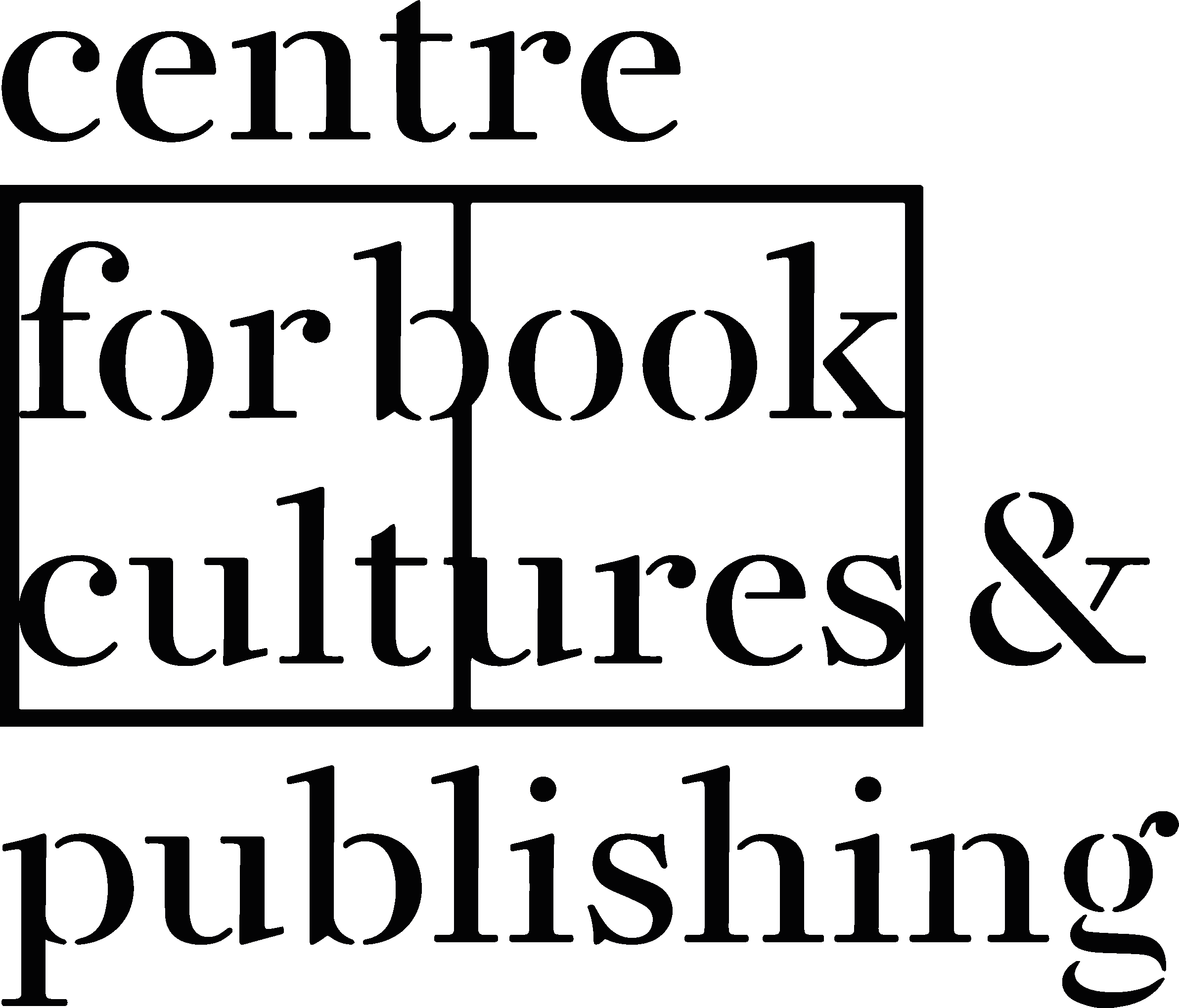

The description of Ratty and Kathleen’s efforts – translating word by word, navigating their way through the maze of Latin grammar, eventually arriving at the conclusion that a strange-sounding sentence is justified by the “odd” qualities of Virgil’s heroine – may well bring a smile to our faces, but there is a clear lesson to be drawn from this opening of Keary’s novel: Victorian children were no novices when it came to translation, which often served as a means of learning foreign languages. On the other hand, we see the young translators err, stumble and fall on their journey towards the art of translation: chapter III of The Cousins and Their Friends features an illustration of Kathleen tumbling down the stairs with her dictionaries and grammar books. Certainly, at times translation could be for children quite literally a painful and bruising experience. Most often, however it was a source of pleasure, amusement and entertainment, especially when it involved reading translations rather than actually producing them.

Invisible Storytellers

Of course, in the Victorian era, children tended to translate solely for the purpose of the schoolroom. Books by foreign authors in the bookcases of the nurseries – beacons of what was new, unfamiliar, and fascinating – reached young readers through transfers provided by adult translators. As noted by Emer O’Sullivan, children’s literature has been “a site of intense translational activity since its inception” (O’Sullivan 2013: 451), translations being a key factor in its development. For example, various versions and adaptations (primarily for children) of Defoe’s The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe made its way across Europe in a glorious success: in France, it provided Jean-Jacques Rousseau with a model for reading to his ideal pupil Emil (Émile, ou De l’éducation, 1762); it came to Germany in Joachim Heinrich Campe’s influential version (Robinson der Jüngere, 1779) (see Nikolajeva 2016: 16); in Poland the best-known adaptation for the young audience was penned by Władysław Ludwik Anczyc (Przypadki Robinsona Crusoe,1868), which continued to be a favourite children’s reading for generations.

Thus translators were and are among the most important agents in (not only) children’s literature. But they were often – especially in the early stages of its evolution – marginalized and placed in the distant background. Sometimes they were not mentioned at all on the title page of a book “from German”, “French” or “Italian”, sometimes hidden under pseudonyms or initials – “the great disappeared of literary history”, as Gillian Lathey called them (Lathey 2014: 1). The translator’s fate was frequently to be “invisible”, to remain in the shadow of the author or the text; their task was to transfer the original into the target language in a seamless, transparent way (see Venuti 2008) and then vanish into thin air, or at least remove themselves away from the readers’ interest. This is even more true for the translators of children’s texts, since, as Zohar Shavit pointed out, children’s literature is positioned on the periphery of general literature (see Shavit 1981), and thus its translators are placed, as it were, on the “margins of the margins”, becoming “invisible storytellers” and “the most transparent of all” (Lathey 2010: 5).

Translator’s Own Paper?

When I embarked on my intellectual adventure at the University of Reading’s Special Collections, I set myself a clear-cut task: to find the hiding places of translators in the peculiar and, it might seem, even less translator-friendly form of writing for the young – that of children’s periodicals. For whereas in published books translators occasionally manage to step out of the shadows into the daylight – as evidenced, for example, by their prefaces, which, although rare, give them a voice and ensure their visibility (Lathey 2014; Fornalczyk-Lipska 2021) – the translations published in the press seem to even less frequently allocate a space in which their authors can be noticed. And yet translations and adaptations published in periodicals played an important role in the evolution of British children’s literature, helping to develop new conventions in domestic writings: William Makepeace Thackeray, before writing The Rose and the Ring, published an excerpt from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Nutcracker in The National Strand, while several of Andersen’s fairy-tales appeared in Good Words for the Young, a magazine edited by George MacDonald, in which his novel At the Back of the North Wind, marked by a clear affinity to The Snow Queen, was serialised.

The aim of my project was therefore to explore Victorian children’s periodicals, firstly to find out in what proportion the translated literature was represented there (which authors were translated, from which languages and cultural contexts; which types of texts were most often subject to interlingual transfer; what were the subsequent stages of reception of a given text/author – whether publication in a periodical opened the way to book publication and enabled a wider readership). Secondly, and above all, I set out to find the traces of those “most invisible of all” who constantly play a (forced) game of hide and seek with us: if possible, to find out who the translators working for the periodicals were, whether they left their signature in the texts (in form of prefaces, footnotes, accompanying articles etc.), in which periodicals – if in any – they were most visible, and what this tells us about the position of the translators at the time. My research was guided by the trend recently taking off in the Translation Studies, namely Literary Translator Studies (cf. Kaindl, Kolb, Schlager 2021) which focuses our attention on the translators and puts them at the forefront. Exploring the question of the translators’ visibility in the British Victorian children’s press seemed all the more important as it has rarely been the subject of scholarly reflection (cf. Drotner 1988, Sumpter 2008). Here I would like to present some of the most interesting findings from my search of “where the translators hide” in Victorian children’s periodicals available in the University of Reading Special Collections. My examples come from only one magazine, as it turned out that the traces of translators in all the periodicals I researched are so numerous and fascinating that I would not be able do them justice in this short text.

Mrs. Gatty puts her best foot forward: Aunt Judy’s Magazine

Aunt Judy’s Magazine, founded in 1866 by Margaret Gatty, proved to be the most abundant in the traces of the translators’ presence. Designed for “the use and amusement of children”, the aim of the periodical was “to provide the best of mental food for all ages of young people, and for many varieties of taste” [1], as the Introduction reads. Mrs. Gatty fulfilled this claim also by including in her magazine translated texts, both poetic and prose, from various languages. For example, the Christmas Volume of 1866[2], featured a translation of a poem by the Danish Romantic writer Adam Oehlenschläger (who authored, among other things, the lyrics to the Danish national anthem). Underneath this verse, titled Teach me[3] (originally Lær mig, o skov, at visne glad, published in 1813), we find the initials “J.H.G.”, which makes it possible to assume that it was translated by Juliana Horatia Gatty, the daughter of Mrs. Gatty and the children’s author Juliana Horatia Ewing in later years. For the same Christmas Volume she also translated a short story by Robert Reinick, published as A Child’s Wishes (From the German of R. Reinick) [4], as well as “A Dramatic Dialogue, from the French of Jean Macé” titled War and the Dead[5]. The 1866 Christmas Volume also contains translations by Mrs. Gatty, who translated Les Animaux de Paris as The Animals of Paris (From the French of Jean Macé) [6]; it is signed Ed., that is with the abbreviation that marked texts written by the Editor, Mrs. Gatty herself.

She was also most likely the author of the two reviews that appeared in the 1866 Christmas Volume, both dealing with key authors and texts in world children’s literature: the first was on Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, published in the previous year, and the second on Hans Christian Andersen’s collection of fairy tales, What the Moon Saw, and Other Tales with illustrations by A. W. Bayes, engraved by the Brothers Dalziel and translated by H.W. Dulcken (who also wrote a short Preface to the volume), published also in 1865 (dated 1866) [7] . Admittedly, in her review of Andresen’s fairy tales, Mrs. Gatty does not mention the translator by name, thus rendering him somehow invisible. It is a pity, since Dulcken was an educated (holding a doctoral degree) and meritorious translator from German and Danish, known above all for his renderings of Andersen (see Pedersen 2004: 164). In contrast, the review mentions the name of What the Moon Saw illustrator, which seems to underline the hierarchy of prestige still in force in today’s children’s publishing, according to which that the illustrator’s name often appears on the covers, but very rarely together with the name of the translator. It is important to note, however, that in her review Mrs. Gatty does not omit the issue of translation altogether – even though she hides the translator from her readers, she pays attention to the translation itself, describing it as one of the book’s strengths (“the translation reads quaintly and charmingly”), and emphasising the translator’s involvement in the selection of the stories for the reviewed volume.

Even better in terms of the translators’ visibility stands the 1867 Aunt Judy’s Magazine Christmas Volume. It again features Andersen, as if heralded by the previous volume. This time, however, he is no longer a subject of a review, but appears “in person”, by way of his translated tale “The Will-o’-the-Wisps are in Town”, Said the Moor-Wife. Also, in this instance the translator is neither omitted nor hidden away behind the initials, but present in the full glory of her first and last name, as announced in the note “Translated by Augusta Plesner” [8] just below the title. Interestingly, in the same year a collection The Will-o’-the-Wisps are in Town, and Other New Tales was published by Alexander Strahan, translated by Plesner and S. Rugeley-Powers. The same illustration that accompanied the fairy tale in Aunt Judy’s Magazine was used as the frontispiece for this edition, we can therefore assume that these two publications were related, most likely the one in the periodical was intended to serve as an advertisement for the newly published collection.

Another translation published in the Christmas Volume of 1867 was Popular Tales from Andalucia, as told by the peasantry (Translated from the Spanish) [9]. Here the author of the translation, C.[aroline] Peachey (who nota bene was also the translator of Andersen[10]), is not only mentioned by name, but there are other signs of her presence. These are, most notably, the footnotes and the short preface, which addresses, among other things, the question of censorship („The first of the series has been abridged, to avoid allusions bordering on the profane”[11]) and mentions the author of the source text. This case proves therefore to be an example of remarkably strong translator’s visibility since, according to my research, situations in which the translators working for periodicals were given space for a preface were extremely rare. There is but one blot on this (otherwise rosy) landscape: next to Popular Tales from Andalucia there we will find no explicit information that Peachey was their actual translator – yes, her name appears under the preface, so readers could rightly guess that she translated the tales, but one could also assume that she wrote her preface as an expert or perhaps an editor. The information missing from the text – “translated by C. Peachey” – can instead be found in the table of contents of the 1867 Christmas Volume. A game of hide-and-seek with the translator indeed!

The example that is the icing on the cake, in a word the most fascinating, captivating and exciting example of the translator’s visibility, I have left for the very finale. One of the highlights of Aunt Judy’s Magazine were the monthly Memoranda written by Mrs. Gatty herself (again signed Ed.), described in the above-quoted Introduction to the first volume as the antidote to “an overflow of mere amusement”; they were “things to be remembered in each month – […] facts and anecdotes, historical, biographical, or otherwise, deserving a niche in the brain-temple of the young” [12]. The memorandum of a particular interest in the context of the translators’ visibility comes from July 1867, so (what a coincidence!) it was written exactly 156 years before I was carrying out my research at the UoR Special Collections in July 2023. The first entry is dated “A.D. 1724 – 2 July”, and it commemorates the birth of the German poet Frederick Theophilus Klopstock (i.e. Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock). However, the readers of Aunt Judy’s might well have been surprised to learn that it is not Klopstock’s biography that the memorandum begins with, but… the biography of his translator, Elizabeth Smith (1776–1806). This biography, penned by Mrs. Gatty, is of such an importance by way of shedding light on the too-often marginalised, swept under the carpet and hidden in the (literary) wardrobes figure of the translator, that it is worth quoting it here in full:

It is now nearly sixty years ago, since the publication of certain “Fragments in Prose and Verse,” (by a young English lady who died early of consumption,) made the name of Klopstock familiar to English ears. The young lady was a Miss Elizabeth Smith, who, at a time when education was not generally carried to anything like the extent that is now the fashion, was very little behind Lady Jane Grey herself in the variety and extent of her learning and acquirements. She was one of several children, and no unusual pains were taken with her education, but she had the one advantage of being born in a house with a fine library; and this seems to have been enough to fire her literary tastes. At thirteen, she is described by Miss Bowdler (her biographer) as “excelling in everything she attempted”. Music, dancing, drawing, French, Italian, geometry, and some other branches of mathematics, were then her favourite pursuits; and to these she soon added Italian, Spanish, Latin enough to read Cicero so as to enjoy it, something of Arabic and Persian, Greek, Hebrew, and German, then but little read or thought of. The list sounds like an invention, but the truth of Miss Bowdler’s statements is fully confirmed by the young lady’s own letters, written to friends from the age of thirteen upwards. Yet she had no regular instruction, except in French and the merest rudiments of Italian: a fact which may show our young readers how much more depends on themselves than their “schoolmasters,” let them be who they may.

In 1803, Miss Smith extraordinary talents having been made known to one of the literary man of the day, Mr. Sotheby, (himself a fine German scholar,) he suggested that she should be employed on some work which might have an interest for the public; and that fixed on was a translation of certain papers and memoirs relative to the poet Klopstock and his wife. No small interest had been excited about the latter by the publication of some of her letters to Richardson the novelist in his “Correspondence,” and through Mr. Sotheby and Miss Bowdler the necessary books were procured, and for about two years Miss Smith occupied her leisure hours in the pleasant task of translation and compilation. Fatal illness then set in, but the papers left unpublished at her death were brought out, in 1808, by Miss Bowdler, forming a second volume of the “Fragments in Prose and Verse” – a second volume, so singularly unlike the first in some respects, though so harmonious with it in others, and each so interesting, that one might almost take Meta Klopstock [Margareta, the wife of Friedrich Klopstock and a writer herself; addition my – A.W.] and Elizabeth Smith as types of the highest case of national female character.

And through these two women the poet Klopstock himself became familiar name with young English people, and they learnt that he had written an epic poem on the Messiah and a great many beautiful odes; that he and his wife loved each other unusually dearly; that she wrote “Letters from the Dead to the Living;” and he, after her death, wrote “Letters from the Living to the Dead.”[13]

Mrs. Gatty does Elizabeth Smith justice by bringing her out of the shadow that is typically the fate of translators and placing her in the full light of reader’s attention. The importance of the translator’s person is emphasized all the more because her biography precedes that of the German poet, although he is, after all, the main “subject” of the memorandum. It is also intriguing that Mrs. Gatty focuses precisely on Miss Smith’s personal history, rather than on the quality or quantity of her translations (although she translated not only from German but also passages of the Bible, including the Book of Job published in her translation in 1810; a few years later A vocabulary, Hebrew, Arabic and Persian, by the late Miss E. Smith was also published). In her text Mrs. Gatty highlights, above all, the aspect of self-education and the thirst for knowledge crowned with success, thus employing the biography of the translator-polyglot, who introduced Klopstock’s work to English literature, as a kind of role model for young readers of Aunt Judy’s Magazine (it is worth noting that Elizabeth Smith was also listed in Women worth Emulating by Clara Lucas Balfour, published in 1877 for Sunday school purposes).

Aunt Judy’s Magazine, thanks to the efforts of Mrs. Gatty, can be praised as one of the Victorian children’s periodicals that promoted the translators’ visibility in a unique way: from translations with marked authorship to the exceptional case of putting the translator on a pedestal and giving her biography as a model of a meaningful life. However, other periodicals of the time also boasted a significant proportion of translations – one of these was surely Good Words for the Young, in which the proportion of texts from Russian is particularly interesting. On the other hand, there is The Children’s Friend, established by Rev. William Carus Wilson (believed to inspire the antipathetic Mr. Brocklehurst in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre) – although it published hardly any translation at all, it surprises with a biographical note dedicated to the two young Nigerians who helped to translate the Bible. But of them – as well as other finds from the Special Collections – I will recount on some future occasion. As for today: may our translators always be visible, not just in children’s periodicals and not only during the celebrations of International Translation Day.

Acknowledgments: My warmest thanks go to Sophie Heywood and Nicola Wilson for welcoming me to Reading and making this research possible. Many thanks also to Michele Drisse of the University of Reading Museums and Special Collection for her help with the archives.

References:

Drotner, Kirsten (1988), English Children and Their Magazines, 1751–1945, New Haven and London: Yale UP.

Fornalczyk-Lipska, Anna (2021), “Translators of Children’s Literature and Their Voice in Prefaces and Interviews”, in: Literary Translators Studies, ed. by K. Kaindl, W. Kolb, D. Schlager, Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 183–198.

Lathey, Gillian (2014), “The Translator Revealed. Didacticism, Cultural Mediation and Visions of the Child Reader in Translators’ Prefaces”, in: Children’s Literature in Translation. Challenges and Strategies, ed. by J. Van Coillie and W.P. Verschueren, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–18.

— (2010), The Role of Translators in Children’s Literature. Invisible Storytellers, London and New York: Routledge.

Literary Translators Studies, ed. by K. Kaindl, W. Kolb, D. Schlager, Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Nikolajeva, Maria (2016), Children’s Literature Comes of Age. Towards a New Aesthetic. London and New York: Routledge.

O’Sullivan, Emer (2013), “Children’s Literature and Translation Studies”, in: The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies, ed. by C. Millán and F. Bartrina, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 451–463.

Pedersen, Viggo Hjørnager (2004), “Large-Scale Translations: Dr Dulcken”, in: Ugly Ducklings? Studies in the English Translations of Hans Christian Andersen’s Tales and Stories, Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, pp. 164–175.

Shavit, Zohar (1981), “Translations of Children Literature as a Function of its Position in the Literary Polysystem”. Poetics Today 2(4): 171–179.

Sumpter, Caroline (2008), The Victorian Press and the Fairy Tale, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Venuti, Lawrence (2008), The Translator’s Invisibility. A History of Translation, London and New York: Routledge.

List of images:

- Illustration for The Cousins and Their Friends by Thomas Morten, engraved by Horrace Harral, Aunt Judy’s Magazine, vol. I, no I (photographed by A. Wieczorkiewicz at the University of Reading Special Collections).

- Aunt Judy’s Magazine, Christmas Volumes 1866–1867 (photographed by A. Wieczorkiewicz at the University of Reading Special Collections).

- Elizabeth Smith by R.M. Meadows, after John George Wood stipple engraving, published 1809, National Portrait Gallery, London (Creative Commons).

Endnotes:

[1] Aunt Judy’s Magazine For Young People, edited by Mrs. Alfred Gatty, vol. I, no I, London: Bell and Dadly, 1866, p. 1.

[2] Aunt Judy’s Magazine was published in semiannual volumes, as stated in the publisher’s note: “Instead of numbering the volumes of Ms. Gatty’s young adult series, the publishers decided to call them ‘Christmas volume’ and ‘May volume’ respectively, to better accommodate gifts, awards or birthday presents”.

[3] Ibid., no III, p. 187.

[4] Ibid., no IV, pp. 235–238.

[5] Ibid., no VI, pp. 367–371.

[6] Ibid., no IV, pp. 214–216. Mrs. Gatty had previously translated Jean Macé’s book Histoire d’une bouchée de pain (1861) as The History of a Mouthful of Bread: And Its Effect on the Organization of Men and Animals, published in London in 1864.

[7] Ibid., vol. I, no II, p. 123.

[8] Aunt Judy’s Magazine For Young People, edited by Mrs. Alfred Gatty, vol. III, no XIII, London: Bell and Dadly, 1867, pp. 27–38.

[9] Ibid., no XVI, pp. 230–234; no XVII, pp. 283–286; no XVIII, pp. 364–368.

[10] Her translations, for example, appeared together with those of Plesner in a volume by the same publishing house that issued Aunt Judy’s Magazine: H.C. Andersen, Later Tales, Published during 1867 & 1868, translated by C. Peachey, A. Plesner, and H. Ward, London: Bell and Dadly, 1867.

[11] Aunt Judy’s Magazine, vol. III, p. 230.

[12] Aunt Judy’s Magazine, vol. I, no I, p. 2.

[13] Aunt Judy’s Magazine, vol. III, p. 188–189.

About the author

Dr Aleksandra Wieczorkiewicz is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Polish and Classical Philology and a researcher in the Children’s Literature & Culture Research Team at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. Her academic interests include English children’s literature of the Golden Age, Polish juvenile writings, and children’s literature translation studies. She has authored two monograph books and more than 20 academic articles and book chapters; one of her recent publications concerns the history of influence of the English-language classics on the Polish juvenile literature (in Retracing the History of Literary Translation in Poland, Routledge Research on Translation and Interpreting History, vol. 3, 2021). She is also a literary and academic translator.