By Linda Farthing and Thomas Grisaffi

Originally published in Latin America News Dispatch

Among the many myths about the coronavirus, one of the strangest circulated on Twitter is the belief that snorting cocaine could ward off the illness. But unfortunately for the would-be consumer, as travel has ground to a halt and border controls have tightened, supplies of illicit drugs have dropped.

The coronavirus has de-stabilized the delicate balance in the Andes that the mercurial drug trade relies on. The ramifications reverberate all along cocaine’s supply chain down to the 237,000 families in Colombia, Peru and Bolivia who depend on growing coca leaf. All three countries are currently under lockdown because of COVID-19, enforced by military and police forces. As trafficking routes shrink, in parts of Peru and Bolivia, the price of coca leaf has slumped to one third, or even one sixth, of its previous levels.

A coca leaf plant in Peru’s VRAEM region in January 2020. Photo by Thomas Grisaffi.

“We’re concerned about feeding our families because the price of coca continues to drop,” said Bolivian coca union leader Albino Pinto. “We face restrictions in moving coca and other goods to the central market. This is blocking both local consumption and export, but our production continues at the same level.”

While most of coca leaf production ends up as cocaine, coca growing complements subsistence farming and provides peasant farmers with access to cash income. Coca farmers live in marginal areas, characterized by limited state presence, inadequate infrastructure, and high rates of poverty. The small share of profits they receive slows migration to cities and supports local businesses.

San Francisco, Peru, January 2020. Photo by Thomas Grisaffi.

Each of the three coca-producing countries has addressed the pandemic differently, but the consequences for farmers are comparable across the region. “Illegal drugs are deeply embedded in local societies and are critical to the survival of many impoverished rural households,” explains City University of New York professor Desmond Arias.

But the drop in coca prices does not necessarily mean the cocaine trade has come to a halt.

“What it actually means is that drug traffickers have become more agile in shifting routes and modifying strategies,” according to Kathryn Ledebur of the Andean Information Network. “Given the harsh reality for those who survive at the lowest rungs of the cocaine trade, pandemic control, just like drug control doesn’t stop this business.”

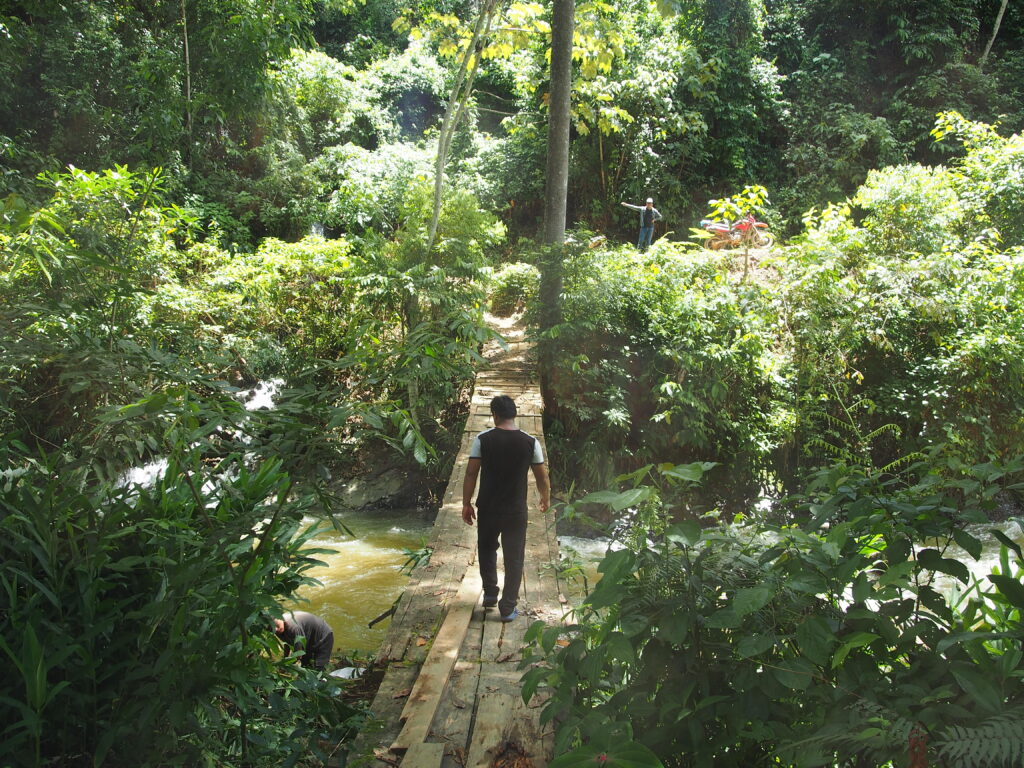

A man crosses a bridge in Peru’s Central Jungle, January 2020. Photo by Thomas Grisaffi.

At the beginning of 2020, coca leaf production stood at a record high in Colombia, the region’s largest grower. Since then, the Duque government has pushed “more intense and aggressive” eradication of coca due to Trump administration pressure, according to the UN Office on Humanitarian Relief. Even though a strict quarantine has been in force since March 24, security forces in eradication operations often lack necessary protective equipment, adding a health threat to the economic one for local farmers.

In Peru, the state drug control agency, DEVIDA, reported on April 30 that coca prices had plummeted 46%. The fallout for local peasant farmers is devastating. “As one of the most remote and marginalized sectors in Peru,” explains a Senior Fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America Coletta Youngers, “coca growers benefit from few government services and face food insecurity. This is exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Hundreds of impoverished Peruvian farmers who migrate seasonally to the lowlands to harvest coca walked home in April because they have a better chance of feeding themselves there.

Coca leaves. Chapare, Bolivia, 2019. Photo by Thomas Grisaffi.

“Government aid reaches those in the cities, but not the poorest in the countryside,” explained

Upper Huallaga union leader, Serafín Luján. “The price of coca in my region has fallen while in the cities, the price has risen and it’s hard to find.”

Bolivia’s interim government led by Jeanine Áñez has taken advantage of the lockdown since March 21 to continue its campaign against its political enemies. Chief among these are coca growers in ousted President Evo Morales’ stronghold of the Chapare.

A man drying coca leaves, Chapare Bolivia, 2019. Photo by Thomas Grisaffi.

The influential Interior Minister, Arturo Murillo, has threatened to isolate and cut off the region, ostensibly because of the coronavirus. Murillo has called “the majority of Chapare residents prisoners of coca grower union leaders and drug traffickers.”

Banks refused to operate in the Chapare because the police had been expelled after Morales’ ouster in November 2019. This prevented residents from accessing one of the three emergency subsidies and loans the government distributed because of COVID-19. For two weeks, no gasoline was available. According to Murillo, this would prevent gasoline being diverted into cocaine paste production. The cut-off killed thousands of fish at operations run by local farmers which rely on gasoline-fuelled aeration pumps.

Travelling by canoe in the Chapare, Bolivia, 2019. Photo by Thomas Grisaffi.

Early in the coronavirus crisis, the growers’ unions, which have deep roots in the region, had distributed food to impoverished people in their region as well as in the cities of Santa Cruz and Cochabamba. Without gasoline, they could not get supplies to people in need.

On April 22, an agreement allowed the police to return under the condition that banks were re-opened, and gasoline distributed. However, gasoline is currently rationed at a levelinsufficient to run the Chapare’s fish farms. There are no gasoline shortages reported elsewhere in the country.

Without alternative economic opportunities, the situation of Andean coca farmers will worsen.

“While much remains unknown about how COVID-19 will impact drug trafficking,” says Youngers, “we do know that disruptions in the supply chain will push these small farmers even deeper into poverty.”

By decelerating global trafficking, it looks as if the coronavirus has achieved what policy makers worldwide have sought for decades but failed to accomplish.

Harvesting small coca plants that are barely one year old, Chapare, Bolivia, 2019. Photo by Thomas Grisaffi.

A farmer admires his coca seedlings. Photo by Thomas Grisaffi.