This blog post is written by Gaston Bacquet, a second-year doctoral student at the University of Reading’s Institute of Education working under the supervision of Prof. Carol Fuller and Dr. Anna Tsakalaki. Here, he reflects on his latest findings regarding how learning a language can increase someone’s degree of social inclusion, and the role of teachers and policy makers in facilitating that process. Gaston’s research interests include learner identity, investment and empowerment in language learning, multiculturalism and inclusive education. His PhD research will attempt to investigate how languages can be used to achieve further social inclusion.

Let’s begin with language

In his book ‘Language and Identity’, John Edwards (2009) suggests that identity is a summary of all our individual traits and characteristics, and that it defines our uniqueness as humans. Unlike others after him, however, he also suggests that this uniqueness does not arise from possessing components that are strictly our own, but rather from what he called “a deep and wide range of human possibilities” (p.25).

Amongst these possibilities, and because it is central to the human condition, we find language. Some researchers have deemed it of such importance so as to consider it inseparable from identity and intrinsically linked to the human condition and self-development. Others have found evidentiary support to link language learning and the construction of one’s identity (Edwards, 2009; Joseph, 2004; Norton, 1997).

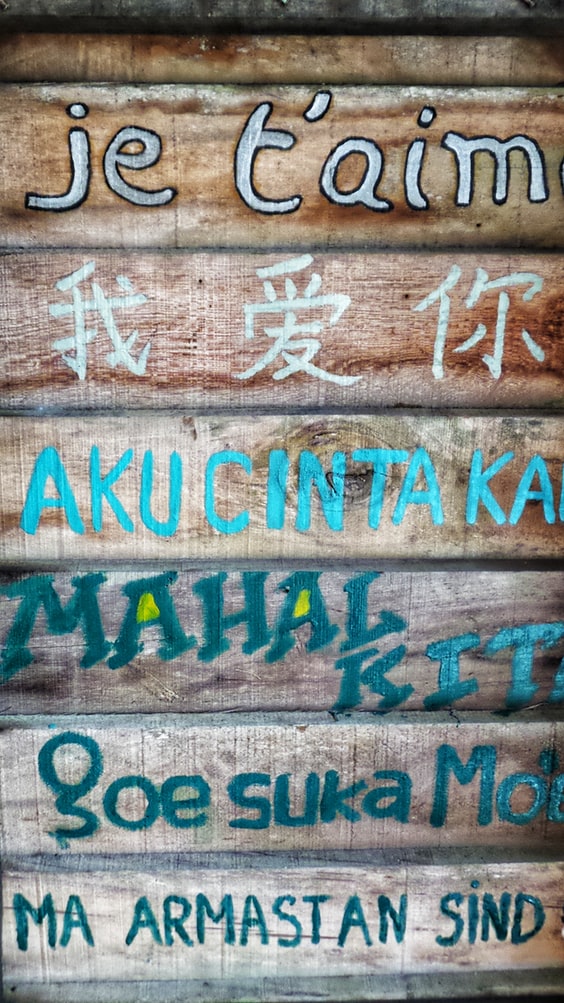

What is certain is that as arbitrary as languages are, they provide individuals with a sense of belonging and community; since the early 20th century researchers have noted how certain groups use their language to protect themselves from outside influence and even to be able to maintain their traditions and culture (Morris, 1946; Steiner, 1994). It follows then that a common language (a lingua franca) serves as a means by which to bridge a gap between communities that might be otherwise isolated from each other. Not only English is at play here as the international language for business and diplomacy, but there is also the case of Arabic all across the Middle-East and North Africa, and Chinese throughout the Malay peninsula all the way to Singapore. In both of those cases the religious and cultural implications are broad and have repercussions in employment, social mobility and more importantly, social and cultural inclusion. It is this last point I would like to focus on.

What is social inclusion?

To understand what social inclusion is, let’s begin by grasping its opposite. The UN ‘Report on the World Social Situation’ (2016) defines social exclusion as “a multidimensional phenomenon not limited to material deprivation; poverty is an important dimension of exclusion, albeit only one dimension” (p.17). When we talk about social exclusion we mean to describe any context or situation in which an individual is unable to fully take part in the life of their community, be it socially, culturally, politically or economically.

By contrast, social inclusion is “a process which ensures that those at risk of poverty and social exclusion gain the opportunities and resources necessary to participate fully in economic, social, political and cultural life and to enjoy a standard of living that is considered normal in the society in which they live. It ensures that they have greater participation in decision making which affects their lives and access to their fundamental rights” (Commission of the European Communities, 2003, p. 9). In other words, social inclusion seeks to improve the conditions of individuals so they are more able to participate fully in the life of the society they belong to.

What can we do?

Let’s explore the role of language in such process. Some scholars (Grin & Vaillancourt 2000; Kymlicka & Patten 2003; Laitin & Reich 2003; Patten, 2001; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2008) consider languages a human right to be recognized as an individual asset, while others view them as human capital which might enhance a person’s possibilities to improve their job prospects (Grenier 1982; Lazear 1995; Pendakur & Pendakur 2002). Regardless of this seeming dichotomy, however, what is clear that both of these notions fall under the concept of social inclusion, since language knowledge has the potential to help the learner gain greater opportunities and access, thus enabling them to participate more fully in their societal life.

The February 2018 “Statement for a Multilingual World” issued by the Salzburg Global Seminar, gives some interesting numbers I think worth exploring. For instance, in a number that illustrates how multi-lingual our world really is, there are 7,097 languages in the world; yet about one-third of them are endangered and only 23 dominate and are spoken by more than half of our planet’s population. There are also 244 million people who are considered international migrants, of whom more than 20 million are refugees (a number that has continued to increase since 2000) who are in need of access to jobs, schools and opportunities but who also face stringent language requirements in order to qualify for such access.

The statement also points out the need for targeted policies that can improve social cohesion in order to achieve further social and political diversity, given a recent shift towards denying the right for communities to maintain their linguistic identity.

A case in point is a report by Lo Bianco (2017) on multi-ethnic conflict in Thailand and Myanmar, two countries with a history of language-based conflict; that report illustrates how language is being used to defuse conflict through a method he calls “facilitated dialogue” (p.2), in which a facilitator assist the parties involved in achieving a higher degree of understanding through a structured program of sharing views and collaborating through language.

Conclusion

We can conclude by stating that there is an indelible link between language learning and social inclusion; that in practical terms, such inclusion means opening avenues for second language users to become more integrated members of their communities, and that a common language, whatever it may be, is key to facilitate that.

It falls on teachers and policy makers to engage in targeted practices that can help second-language learning communities gain further access to education and jobs through making language requirements more accessible and language learning more easily accessed.

References

Commission of the European Communities (2003). Joint Report on Social Inclusion summarizing the results of the examination of the National Action Plans for Social Inclusion (2003-2005). Brussels: COM 773.

Edwards, J. (2009). Language and Identity: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grenier, G. (1982). Language as Human Capital: Theoretical Framework and Application to Spanish Speaking Americans. Ph.D. Thesis. NJ: Princeton University.

Grin, F. & Villancourt, F. (2000). On the financing of language policies and distributive justice. In R. Phillipson (Ed.), Rights to language: Equity, Power and Education (pp. 102-110). New York, NY: Lawrence Elburn Associates.

Joseph, J. (2004). Language and Identity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kymlicka, W., & Patten, A. (2003). Language Rights and Political Theory. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 23, 3-21.

Lazear, E. (1995). Culture and Language. Working Paper 5249, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Laitin, D. & Reich, R. (2003). A liberal democratic approach to language justice. In W. Kymlicka, & A. Patten (Eds.), Language Rights and Political Theory (pp. 80—104). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Morris, C. (1946). Signs, Language and Behavior. Oxford: Prentice-Hall

Norton, B. (1997). Language, Identity, and the Ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429.

Patten, A. (2001). Political theory and language policy. Political Theory (29), 683–707.

Pendakur, K., & Pendakur, R. (2002). Language as Both Human Capital and Ethnicity. International Migration Review, 36(1), 147–177.

Regester, D., & Norton, M.K. (2018). The Salzburg Statement for a Multilingual World. European Journal of Language Policy, 10(1), 156-162.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2008). Linguistic genocide in education – or worldwide diversity and human rights? New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Steiner, H. (1994). An Essay on Right. Oxford: Blackwell.

UN DESA (2016). Identifying social inclusion and exclusion. Report on the World Social Situation 2016: Leaving no one Behind: The Imperative of Inclusive Development, UN, New York.