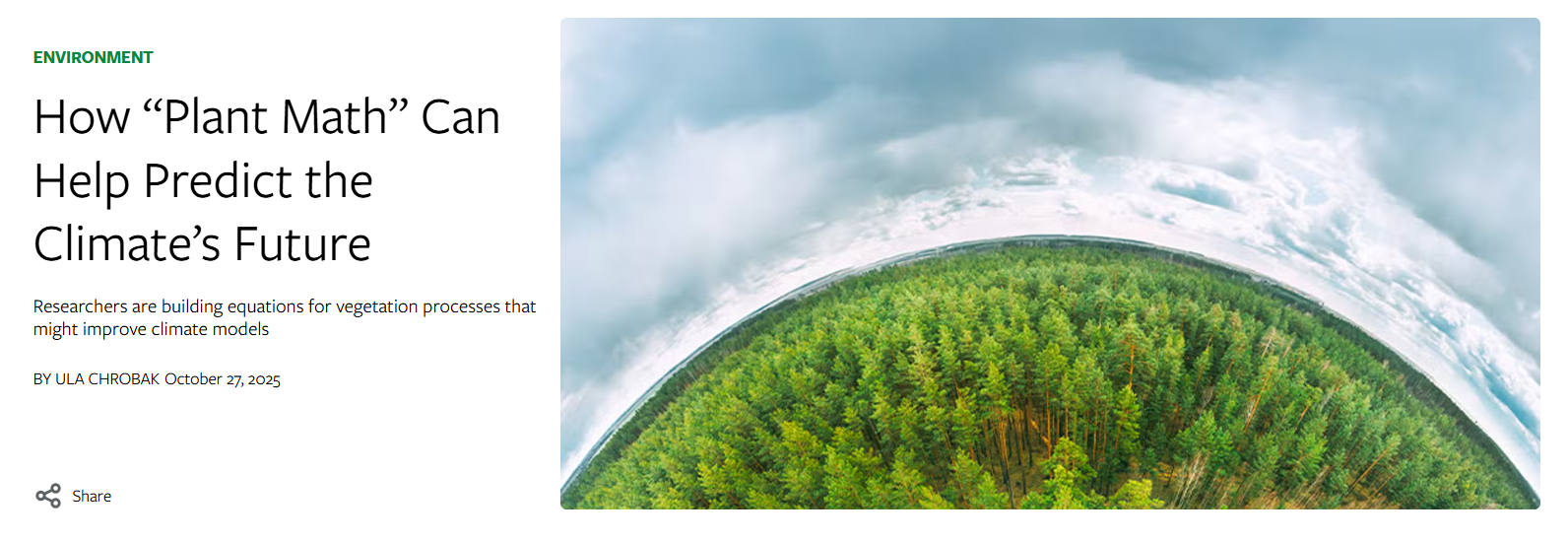

We’re delighted to see our work just featured in Nautilus Magazine, a publication known for its deep dives into science, culture, and the connections between them. The article, How “Plant Math” Can Help Predict the Climate’s Future, explores how LEMONTREE researchers are transforming the way plants are represented in global climate models.

We’re delighted to see our work just featured in Nautilus Magazine, a publication known for its deep dives into science, culture, and the connections between them. The article, How “Plant Math” Can Help Predict the Climate’s Future, explores how LEMONTREE researchers are transforming the way plants are represented in global climate models.

For those who have been following our work for a while, this won’t come as news, but it’s wonderful to see the broader significance of LEMONTREE’s research gaining attention in a respected outlet, and it serves as a timely reminder of the work we have done and still aim to do.

The piece features insights from LEMONTREE’s Prof Sandy Harrison, Prof Colin Prentice, Prof Pier-Luigi Vidale, along with Prof Julia Green (who was previously funded through LEMONTREE). Together, they explain how a new generation of “plant maths” is helping to bridge the gap between theory, field data, and Earth system modelling.

Why plants matter in climate models

Early climate models were surprisingly simple with land surfaces treated as bare ground, where rain “fell into buckets” before evaporating back into the atmosphere. Over time, models evolved to include vegetation, becoming increasingly complex, but these representations have remained fairly coarse, and largely inaccurate.

Most global models today divide the world’s plants into just a handful of “functional types” with fixed traits and responses. That means the simulated forests and grasslands in these models don’t fully capture how real plants adapt to changing conditions such as drought, warming, or rising CO₂.

As Sandy Harrison explains, “The idea is that we can simplify the models that we use to predict how plants react to climate—and also how they will then influence the climate.”

The theory behind the equations

LEMONTREE’s approach is guided by the principle of eco-evolutionary optimality (EEO), the idea that plants have evolved to balance trade-offs between resource use and survival. In other words, vegetation tends to optimise its behaviour: adjusting leaf area, photosynthetic capacity, and water use to achieve the best outcome for growth given local conditions.

For instance, plants must open their stomata to take in CO₂ for photosynthesis, but doing so also releases water. The optimal strategy balances these competing demands, allowing plants to thrive without drying out.

By expressing these trade-offs mathematically, we are developing simple but powerful equations that describe dynamic key processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, and water transport. Colin Prentice explains that a single equation built from this theory can often replace several more complicated empirical ones, making the models both simpler and more accurate.

Why our theory matters

Better representation of plant behaviour isn’t just a detail; it’s one of the biggest uncertainties in climate projections. Whether plants will continue to absorb carbon under future warming, or whether drought and heat stress will turn ecosystems into carbon sources, remains an open question.

As Pier-Luigi Vidale notes, “We would like to do away with all these parameters that describe what vegetation does, and try to compute those things dynamically.” This shift means climate models can simulate plants as active, adaptive agents in the Earth system rather than passive background elements.

Julia Green points out how satellite data reveal that current models often underestimate how strongly plants respond to drought. Small discrepancies like these can cascade into large differences in predicted carbon and water fluxes, something LEMONTREE’s new equations are designed to fix.

From equations to Earth system models

Whilst LEMONTREE is due to end in June 2027, our work is already feeding into broader international collaborations. One of these is CONCERTO (improved CarbOn cycle represeNtation through multi-sCale models and Earth obseRvation for Terrestrial ecOsystems), a European Union–funded project that brings together experts to refine how vegetation and the carbon cycle are represented in global climate models.

CONCERTO, which is already underway, includes LEMONTREE scientists such as Colin Prentice among its core contributors. Together, the projects are testing how the new generation of plant equations, developed from eco-evolutionary optimality theory, can improve the simulation of interactions between vegetation, water, and the atmosphere across scales.

This partnership ensures that the “plant maths” developed within LEMONTREE doesn’t remain theoretical, it’s being embedded directly into the models that will help shape future climate projections.

“We still really need to develop models and to take big risks, like we’re doing here, the indication so far is that it’s working.” Pier-Luigi Vidale.

A shared step forward

As the Nautilus article captures, the real strength of LEMONTREE lies in our collaborative nature—between theory and data, between ecologists and climate modellers, and between projects like LEMONTREE and CONCERTO.

By updating the “language” of plants in climate models, we are not only improving how we simulate the carbon cycle, we’re also helping to understand the living dynamics of our planet in a changing climate.

You can read the full feature in Nautilus Magazine here.