Understanding how vegetation responds to environmental change is one of the most pressing challenges in Earth system science. Working Group D of the LEMONTREE Science Project is tackling this problem by focusing on vegetation dynamics and functional diversity—key aspects of terrestrial ecosystems that determine how plant communities persist, shift, and adapt under changing climates.

Led by Associate Professor Han Wang and ECR Huiying Xu (both of Tsinghua University), the group aims to provide a strong basis for representing functional diversity in vegetation models, particularly how leaf and hydraulic traits influence ecosystem structure, function, and dynamics. The group’s approach is two-pronged: first, using fieldwork to understand how traits vary across species and environments; and second, using models to test how these trait-environment relationships can improve predictions in land surface models (LSMs).

In our most recent LEMONTREE Science Meeting we had a presentation from Yongqiang Wang, examining how tropical tree species in Southwest China recover from drought, shedding light on how hydraulic traits shape growth and recruitment. The second presentation by Yuzhi Zhu, explored how leaf and fine root traits relate across spatial scales, revealing both decoupling and convergence depending on environmental context. Together, these talks highlighted the nuances of plant strategies and their implications for future vegetation modeling. Here are the summaries of their talks.

Multiyear droughts reshape post-drought growth recovery and recruitment of tropical tree species in Southwest China

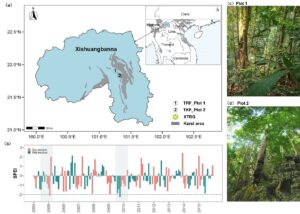

In the first talk, Dr. Yongqiang Wang, a postdoctoral researcher at Tsinghua University, presented findings from a long-term study on how tropical trees recover from drought, with a specific focus on the role of hydraulic traits in shaping growth and recruitment responses. The study was conducted in two tropical forest plots in Southwest China in the Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve —one representing a wetter rainforest, and the other a drier karst forest—with species monitored 8 times between 2004 and 2015 (Figure1).

Yongqiang began by noting the increasing frequency of climate-induced extreme drought events and their often severe consequences for forest structure and species composition. His earlier work had already established that hydraulic resistance (traits that enable plants to maintain water transport under drought) plays a crucial role in determining tree survival. In particular, species with higher hydraulic resistance (e.g., lower P50 values) showed lower mortality and increased biomass production during drought (Figure 2).

This new study extended that line of inquiry by asking 2 key questions

- What are the post-drought recovery and recruitment dynamic characteristics of tropical tree species in southwest China?

- Does the hydraulic safety drive the growth recovery and recruitment of trees after drought?

To answer this, Wang’s team assessed tree growth during and after two key drought periods: a single-year drought in 2005 and a multi-year drought from 2008 to 2010 (with extreme drought classified as SPEI less than -1.9). Using indicators such growth resistance, recovery, resilience, and recruitment rates, they analysed responses in 31 tree species. Hydraulic traits were quantified using P50 values (the water potential at which 50% of xylem conductivity is lost) and hydraulic safety margins (for stomata, leaf and branch).

Key findings:

- During single-year droughts, species with high hydraulic risk (low safety) were more likely to recover rapidly after the drought ended. These species appear to maintain higher photosynthesis under mild stress, giving them an early advantage in post-drought growth.

- However, under multi-year droughts, hydraulically safe species (those better able to resist embolism and maintain xylem function) showed better growth recovery. The repeated stress likely exceeded the tolerance thresholds of riskier species, emphasizing the importance of drought frequency.

- Recruitment responses were more context-dependent. During mild droughts, species with greater hydraulic resistance (i.e., higher drought tolerance) tended to show higher recruitment rates, likely because their hydraulic strategy helped young trees survive lower water potentials.

- However, this positive relationship weakened under multi-year drought conditions, where sustained stress may limit the survival or establishment of seedlings. Notably, in the drier karst forest, high drought resistance may threaten the survival of young individuals, possibly due to increased water competition of adult trees or other ecological trade-offs.

- Interestingly, for hydraulically risky species, the recruitment advantage may arise indirectly. These species experience higher mortality under drought, which creates canopy openings and resource space for seedling recruitment. This led to a positive correlation between adult mortality and recruitment, suggesting a self-replacement mechanism rather than direct drought tolerance benefits.

In summary, the study found that the influence of hydraulic traits on post-drought recovery and recruitment is strongly shaped by the frequency and duration of drought events. First, a single extreme drought does not necessarily cause lasting hydraulic damage to tropical tree species—especially those with high hydraulic risk (i.e., low resistance), which tended to recover biomass quickly after drought. However, under multi-year drought conditions, species with greater hydraulic resistance (i.e., higher safety) were better able to maintain and restore growth, highlighting the importance of hydraulic safety for long-term resilience.

In terms of recruitment, frequent droughts can actually increase the recruitment of young trees in tropical forests, not because those species are necessarily better adapted to drought, but because high adult mortality opens space and light for conspecific seedlings—a form of self-replacement. These findings challenge linear assumptions about drought responses and underscore the importance of trait-by-environment interactions, particularly as tropical regions face rising drought risks under climate change.

Scale-dependent relationships highlight decoupled leaf and fine root trait variation influenced by common drivers

Yuzhi Zhu, a PhD student from Tsinghua University presented his group’s work on the scale-dependent relationship between leaf and fine root traits, addressing a central question in plant functional ecology: Do above- and below-ground organs vary together along a shared economic strategy, or do they respond independently to environmental drivers?

He began by outlining the theory of plant economic spectra. The leaf economic spectrum (LES) is well-established and describes a trade-off between traits associated with resource acquisition and conservation — for example, from high leaf nitrogen (fast, acquisitive strategy) to high leaf mass per area (slow, conservative strategy). Fine roots, although historically less studied, are now also recognized as following two economic axes:

- A collaboration axis, contrasting specific root length (DIY nutrient uptake) with root diameter (outsourcing via mycorrhizal associations).

- A conservation axis, ranging from high root nitrogen (fast) to high root tissue density (slow).

While these axes capture major trait trade-offs, a central debate remains unresolved: Are leaf and root traits coordinated across these spectra — converging into a unified fast-slow gradient — or are they largely decoupled and independently structured? Some studies suggest alignment between analogous leaf and root traits (e.g., nitrogen content), while others find little or no correlation, proposing instead that root and leaf economics form orthogonal trait spaces.

Yuzhi emphasized that part of this disagreement stems from differences in ecological scale. At local scales, where species coexist within similar environments, trait independence is often observed. But at regional or global scales, with greater environmental heterogeneity, convergence appears stronger — particularly when species-level average traits are used. This, he noted, may be due to environmental filtering or the statistical artifact of averaging individual variation, which can artificially inflate correlation strength.

To clarify this complex pattern, Yuzhi’s study asked: “How do scale-dependent drivers influence leaf-root trait variation?”

He tackled this question by analysing trait coordination at different ecological scales: local (community to biome) and regional to global. His team conducted two major analyses:

- Field data from subtropical forests in Fujian Province, China, including 51 species across two distinct sub-tropical forest communities.

- A global trait dataset (193 local scale sampling sites covering the major biomes across the globe), including both core and “co-predictor” traits for leaf and fine root economics, aggregated at both individual and species levels.

Key findings:

Local Community Scale

- The leaf economic spectrum (LES) and the root economic spectrum (RES) remain internally consistent — that is, traits within each organ type (e.g., high leaf nitrogen with low LMA, or high root nitrogen with low root tissue density) show the expected correlations that define fast vs. slow economic strategies.

- However, the relationship between leaf and root traits was much weaker or even absent at this scale. For example, species with acquisitive leaf traits did not necessarily have acquisitive root traits, indicating a degree of functional decoupling between above- and below-ground strategies.

- Despite this apparent independence, Yuzhi emphasized that common environmental drivers — such as soil fertility or moisture availability — can still shape trait distributions in both leaves and roots. Thus, trait coordination is not simply a matter of physiological linkage, but may emerge or disappear depending on how environmental factors constrain trait combinations across scales.

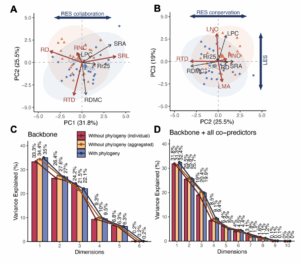

Fig. 3 Decoupled leaf and fine root economics at local scale.

(A-B) PCA biplot for the reduced space constructed using both backbone and co-predictor traits of LES and RES among sampled individuals in the two communities, showing the positions of variables in (A), PC1-PC2 and (B), PC2-PC3 space. Backbone traits are coloured as dark red in the biplot. Co-predictor traits are selected if they have a loading > 0.5 on either one of the principal components marked as LES and RES axes in leaf and fine root trait spaces, respectively. (C-D) Total trait variances explained by different dimensions in principal component analysis with and without considering phylogenetic correlations among all selected species, showing reduced space constructed using only backbone traits of leaf and fine root economics (A), without co-predictor traits and (B), with the inclusion of all co-predictors (LPC, RDMC, SRA, Rr25). As phylogenetically-informed approach needs species-mean data, both individual-level and species-mean (aggregated) data from non-phylogenetically informed approach are present here to facilitate intercomparison.

Regional and Global Scales

- When data were averaged by species, or when multiple local datasets were pooled, stronger trait correlations appeared between leaf and root traits. This suggests that common environmental drivers—such as climate or soil fertility—may promote trait convergence over large spatial gradients.

- A key insight came from dimensionality reduction (PCA). The trait space is best described by three orthogonal axes—two root axes (collaboration and conservation) and one leaf economic axis. This multidimensional structure indicates that functional diversity cannot be collapsed into a single universal spectrum.

- Importantly, Yuzhi demonstrated how data aggregation affects ecological inference. Species-averaging processes can artificially inflate trait correlations, masking the real variation present at the individual or local scale.

In summary, Yuzhi’s study shows that leaf and root trait coordination is scale-dependent. At local scales, these traits often vary independently, reflecting organ-specific responses to above- and below-ground resource pressures. But at regional scales, patterns of coordination can emerge—not due to direct trait coupling, but because of shared environmental drivers and species-level trait averaging. These findings highlight the importance of accounting for scale and environmental context when using trait data in ecological models and Earth system simulations.

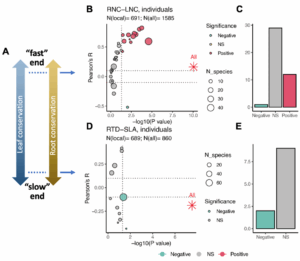

Fig. 4 Scale-dependent covariation of leaf and fine root economic traits from local to regional scales.

(A), Conceptual framework illustrating the leaf economics spectrum and the analogous conservation gradient in fine root trait space. (B-E), Results of bivariate correlation analyses between functionally analogous leaf and fine root traits across individual local-scale studies, showing: (B–C) The acquisitive end of leaf and fine root economics: relationships between root nitrogen concentration (RNC) and leaf nitrogen concentration (LNC), and (D-E) The conservative end of leaf and fine root economics: relationship between root tissue density (RTD) and specific leaf area (SLA). Red asterisks in panel B and D indicate correlation results when pooling data from all sites. Significance statistics denote P<0.05 and absolute R value >0.1.

Toward Better Models of Vegetation Dynamics

Both talks from Working Group D underscore the value of integrating functional trait data with ecological modelling. From species-specific drought recovery patterns to the scale-sensitive relationships between traits, these studies show that plant strategies are both context-dependent and deeply structured by trait-environment interactions.

These findings also reinforce one of LEMONTREE’s central missions: to improve the representation of vegetation dynamics in land surface models. By explicitly incorporating trait variation, demographic processes, and scale-awareness, future models will be better equipped to predict how ecosystems respond to climate extremes, resource change, and disturbance regimes.

Functional diversity is not a single axis but a multi-dimensional space, shaped by complex biological and environmental forces. Capturing that complexity, while making it usable for large-scale modelling, whilst challenging, will be essential for building a more robust, predictive science of vegetation change.