By Dr Rebecca Bullard, Department of English Literature, University Reading

Jane Austen would, I think, have been delighted to feature on the new £10 note. Many of her novels are about the impact of money – and especially the lack of it – on women’s lives.

Her first published works, Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice, feature families full of daughters struggling under a legal system that keeps all property in the hands of (sometimes distant) male relatives. The famous opening of Pride and Prejudice, of course, tells us that ‘a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife’. Austen’s fourth novel, Emma, turns this observation on its head, with Emma Woodhouse declaring that, ‘A single woman, with a very narrow income, must be a ridiculous, disagreeable old maid!’

Austen never condones this kind of snobbery: Emma comes to regret her unkind behaviour towards the impoverished spinster, Miss Bates, and the protagonist of Mansfield Park, Fanny Price, is dignified in poverty. Nonetheless, it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that marrying well for Austen meant, above all, escaping the financial insecurity of a single life; love is a bonus.

Never married, Jane Austen was not shy about the fact that she – unlike any of her novels’ heroines – earned a living by her pen. She took a keen interest in the publication of her novels, always believing in their commercial, as well as their literary, value. She was cross that, in 1812, her publisher would only give £110 for Pride and Prejudice, rather than the £150 that she had hoped for.

During financial negotiations over the second edition of Mansfield Park, she told her niece, ‘I am very greedy & want to make the most of it’. Her letters show that Austen enjoyed spending money as well as earning it. Newly purchased clothes feature frequently in letters to her sister, Cassandra, revealing Austen’s personal taste and her eye for a bargain. Money, it was clear, was a source of pleasure to Austen as well as a resource to be used prudently.

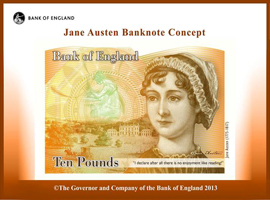

If you look really closely, there are actually two images of Austen on the new £10 note. The larger portrait of Austen’s face, which has attracted a great deal of media attention because it is perhaps not an accurate likeness of the author, shows her looking off into the distance.

The image that I like best, however, has even less claim to ‘authenticity.’ Peer to the left of the main portrait, and you’ll see a fainter image of a woman in Regency-style dress sitting at a twelve-sided writing table, just like the one at the Jane Austen’s House Museum, fully absorbed in her work.

The gravestone that Austen’s family erected to her memory in Winchester Cathedral does not mention her novels at all. It’s great to see that the Bank of England’s newest note commemorates Austen as a professional writer, because that’s how I think she would have wanted to be remembered.

Listen to Dr Bullard’s interview on Jane Austen with BBC Radio Berkshire in our media round-up here