By Dr Patrick Lewis, Associate Professor of Pharmacy

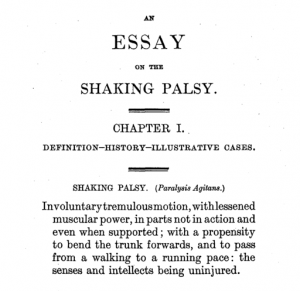

200 years ago the disorder that we now know as Parkinson’s disease was first described by James Parkinson, a surgeon and apothecary who lived in Hoxton, on the edge of the City of London.

On Monday I was fortunate to be invited to a reception at Downing Street hosted by the Prime Minister and Parkinson’s UK to mark this occasion. This brought together people with Parkinson’s, researchers and political leaders to highlight the challenges that are still faced by individuals living with Parkinson’s, their families, friends and carers despite the two centuries of research into this disorder.

Most importantly, there is still no disease modifying therapy – that is, a drug or intervention that either slows down or stops the progress of the brain cell loss that causes the symptoms of Parkinson’s.

I first started working on Parkinson’s in 2005, and in the ten years or more since then I have been witness to some startling advances in our understanding of the disease, many of which have come from learning more about how our genes can influence whether we are more or less likely to develop the disease.

The research in my group focuses on these genetic causes of Parkinson’s, and in particular mutations in a gene called Leucine Rich Repeat Kinase 2 (or LRRK2, pronounced “Lurk two”). These mutations, which are passed down in families through DNA, are the most common genetic cause of Parkinson’s – and this has made LRRK2 of great interest as a potential drug target for this disease. We’re interested in how LRRK2 is involved in controlling a process called autophagy (ort-off-oh-gee), one of the ways that cells get rid of rubbish and recycle unwanted proteins. What we’ve revealed is that when LRRK2 is mutated, or if you switch LRRK2 off using drugs, the way autophagy works is altered.

We think that this might change how the brain deals with aggregated lumps of a protein called alpha synuclein, something that we know is very important for the process that causes brain cells to die in Parkinson’s, and this might have important implications for developing new drugs that can target LRRK2.

We are still some time away from a disease modifying treatment for Parkinson’s, but research from across the globe – including academics in universities and researchers in pharmaceutical companies, working with people with Parkinson’s – is beginning to put forward potential treatments to go into clinical trials.

200 years on from James Parkinson, this means that we won’t have to wait another 200 years for a disease modifying treatment.

Patrick Lewis is an Associate Professor at the Reading School of Pharmacy, where his research is funded by the Medical Research Council, Parkinson’s UK, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the National Institutes of Health and by the Newton fund.