Colonialism has a lingering influence in modern scientific research – and scientists and historians must work together to ‘decolonise’ science, says Dr Rohan Deb Roy in a new post for The Conversation.

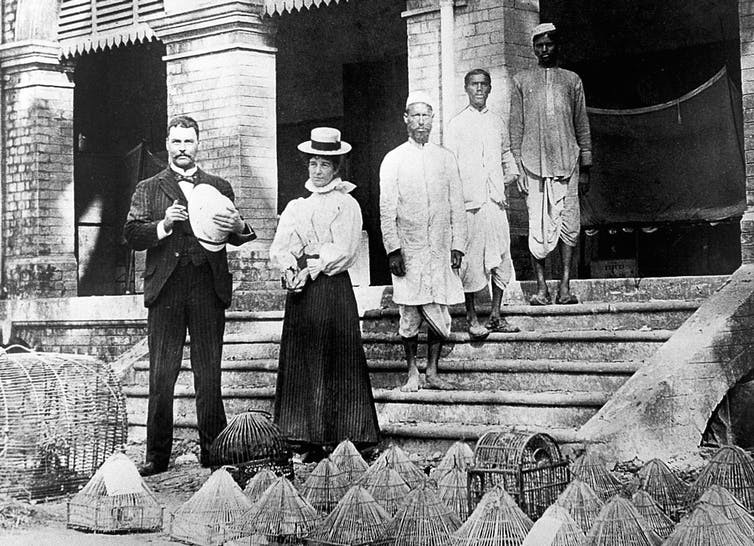

Sir Ronald Ross at his lab in Calcutta, 1898. Image credit: Wellcome Collection, CC-BY-4.0

Sir Ronald Ross had just returned from an expedition to Sierra Leone. The British doctor had been leading efforts to tackle the malaria that so often killed English colonists in the country, and in December 1899 he gave a lecture to the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce about his experience. In the words of a contemporary report, he argued that “in the coming century, the success of imperialism will depend largely upon success with the microscope”.

Ross, who won the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his malaria research, would later deny he was talking specifically about his own work. But his point neatly summarised how the efforts of British scientists was intertwined with their country’s attempt to conquer a quarter of the world.

Ross was very much a child of empire, born in India and later working there as a surgeon in the imperial army. So when he used a microscope to identify how a dreaded tropical disease was transmitted, he would have realised that his discovery promised to safeguard the health of British troops and officials in the tropics. In turn, this would enable Britain to expand and consolidate its colonial rule.

Ross’s words also suggest how science was used to argue imperialism was morally justified because it reflected British goodwill towards colonised people. It implied that scientific insights could be redeployed to promote superior health, hygiene and sanitation among colonial subjects. Empire was seen as a benevolent, selfless project. As Ross’s fellow Nobel laureate Rudyard Kipling described it, it was the “white man’s burden” to introduce modernity and civilised governance in the colonies.

But science at this time was more than just a practical or ideological tool when it came to empire. Since its birth around the same time as Europeans began conquering other parts of the world, modern Western science was inextricably entangled with colonialism, especially British imperialism. And the legacy of that colonialism still pervades science today.

As a result, recent years have seen an increasing number of calls to “decolonise science”, even going so far as to advocate scrapping the practice and findings of modern science altogether. Tackling the lingering influence of colonialism in science is much needed. But there are also dangers that the more extreme attempts to do so could play into the hands of religious fundamentalists and ultra-nationalists. We must find a way to remove the inequalities promoted by modern science while making sure its huge potential benefits work for everyone, instead of letting it become a tool for oppression.

The gracious gift of science

When a slave in an early 18th-century Jamaican plantation was found with a supposedly poisonous plant, his European overlords showed him no mercy. Suspected of conspiring to cause disorder on the plantation, he was treated with typical harshness and hanged to death. The historical records don’t even mention his name. His execution might also have been forgotten forever if it weren’t for the scientific enquiry that followed. Europeans on the plantation became curious about the plant and, building on the slave’s “accidental finding”, they eventually concluded it wasn’t poisonous at all.

Instead it became known as a cure for worms, warts, ringworm, freckles and cold swellings, with the name Apocynum erectum. As the historian Pratik Chakrabarti argues in a recent book, this incident serves as a neat example of how, under European political and commercial domination, gathering knowledge about nature could take place simultaneously with exploitation.

For imperialists and their modern apologists, science and medicine were among the gracious gifts from the European empires to the colonial world. What’s more, the 19th-century imperial ideologues saw the scientific successes of the West as a way to allege that non-Europeans were intellectually inferior and so deserved and needed to be colonised.

Read the rest of this article on The Conversation, where it was first published on 5 April, 2018.

Dr Rohan Deb Roy is Lecturer in South Asian History at the University of Reading. He recently won a Research Outputs prize for early career research for his monograph ‘Malarial subjects: Empire, Medicine and Nonhumans in British India, 1820 -1909’. Judged by the panel as “a work of exceptional originality and significance” the book explores connections between humans and non-humans, and science, medicine and empire.