Is Meghan Markle’s accent becoming more British? Not yet, according to Reading English Professor Jane Setter and colleagues Adrian Leeman and Sam Kirkham from the University of Lancaster, in a recent post for The Conversation.

Fairly soon after her marriage to Prince Harry in May 2018, articles about Meghan Markle started to appear – in the BBC, Mirror, Daily Star and Daily Express – reporting a change in her speech. Apparently the American actress has taken on a “British” accent along with her membership of the royal family.

Markle, a native of Los Angeles, appeared in public with Prince Harry for the first time in September 2017. They became engaged in November the same year and tied the knot in the following May. By July The Express was reporting “people claiming they could hear a British lilt developing” when Markle spoke in public.

People picking up different accents when moving to a new place is not uncommon. In linguistics we call this process “accommodation” – which largely translates to “unintentional imitation”. Talkers accommodate to one another in how fast they speak, the vowels they use and other features. Accommodation also happens non-verbally: in gazing or body posture, for example. Why do we accommodate? Because similarity between people is perceived as attractive and increases efficiency of communication.

This kind of accommodation typically happens unintentionally. A 2007 study showed that speakers accommodate to speech without realising if it is simply played in the background as ambient noise. A study from 2010 showed that when some New Zealand English speakers read positive statements about Australia they used more Australian English vowels. Keep in mind, though, that Markle is an actor – and actors have the skills to change accents intentionally. However, without interviewing her on this issue, we’ll never know if that’s what’s going on.

How can one measure accommodation? This depends on the level of language one wants to study. Here we focus on pronunciation, and a discipline called phonetics. For this article, we analysed a sample of Markle’s speech prior to her engagement to Harry (see above, on Yahoo Style in February 2015) and compared them to more recent ones after she married Harry.

Markle is clearly a practised speaker. In what is billed as her first speech as a member of the royal family, the first clip (above) shows her speaking at a launch event in September 2018 for Together: Our Community Cookbook, for which she has written a foreword. She speaks in a relaxed manner – “with no notes”.

The next clip (below) features her speaking at a more formal occasion: the Endeavour Fund Awards in early 2019. She does have notes this time, but her speech is still very natural sounding, with pauses on occasion for dramatic effect.

Tongue twister

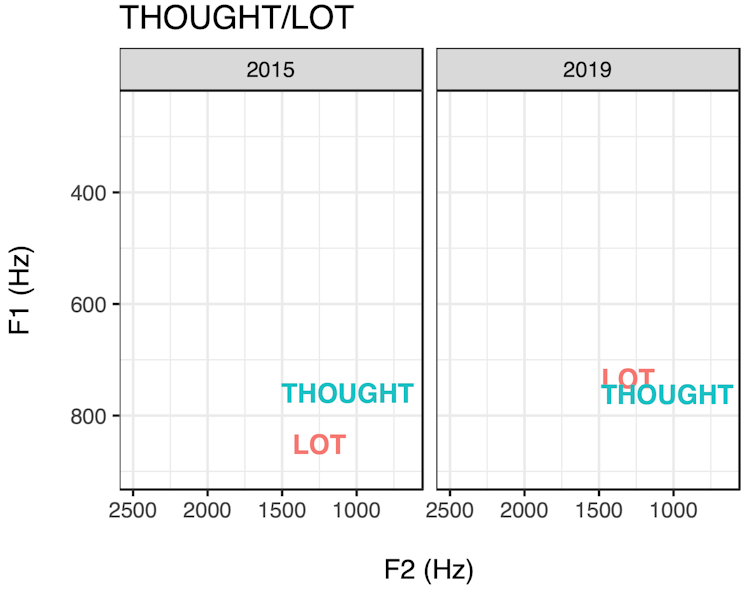

We limited our analysis to these recordings because the audio quality is adequate (acoustic analyses are delicate). We compared three vowels: the vowels in words like “thought” and “talk” and in words like “lot” and “sock” – which are often merged together in California English – and the vowel in words like “price” and “bite”, using three to four examples of each vowel for each of the videos at different points in time. We chose these vowels as, listening to dozens of recordings on YouTube, we felt there may be some change in how she produced them.

The figure below shows something called a vowel plot, which allows us to graph acoustic measurements of the vocal tract resonances from different vowel productions. The Y-axis (vertical) roughly corresponds to the height of the tongue when producing a vowel, and the X-axis (horizontal) shows whether the tongue is front or back in the mouth.

Our preliminary analysis shows that Markle’s articulation of the word “thought” remained virtually identical between 2015 and 2019, while her production of “lot” actually became more similar to “thought” over this period – which is closer to the pattern we might expect in California English. This is arguably the opposite of what we’d expect if Markle was sounding more British.

As for the vowel in “price” – which, technically, is a combination of two vowels, starting somewhere around the southern British English vowel in “strut” and ending closer to the vowel in “kit” – in 2015 (red), her tongue starts relatively fronted and low (starting point of the arrow), which is what one would expect of Californian English. In 2019 (turquoise), her tongue position starts higher than in 2015. The starting point of her 2019 “price” vowel may be moving towards the same vowel sound found in southern English.

A little more talk

So, is Markle really beginning to sound British? The differences reported here are very small, based on a reduced set of (uncontrolled) data, and using only two time points. We certainly can’t deduce from this evidence that she is now speaking with a British accent.

To make more robust claims we need substantially more recent high-quality data – which, at this time, is not available. Furthermore, we would need to expand our analyses to include other vowels and other linguistic domains, such as speech melody, choice of words, or conversational markers – given that “picking up a new accent” is more than merely using different vowels.

New problems, emerge, however: comparing speech melody, for example, between two time points would require us to have recordings of Markle in similar conversational settings at the different times – as a speaker’s melody, or “intonation” as we call it in phonetics, is heavily dependent on conversational context. While we’ve got recordings of Markle speaking to people at public events in the UK since becoming the Duchess of Sussex, we have not been able to find anything like this for her pre-Harry days.

Markle seems to be a woman with a pretty well-defined sense of self. It is unlikely, we feel, that we are going to see profound changes in her accent at this early stage. But anything can happen. And as she says in the cookbook video, she’s keen to celebrate what connects people, not what divides them … and maybe that’s what the media is picking up on.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.