Enslaved women make only fleeting appearances in the historical records from colonial and antebellum America – as property rather than people. But after the Civil War, there was an outpouring of testimonies by formerly enslaved women about their previous abusive relationships with white men. Ahead of her Fairbrother Lecture on 21 May, Liz Barnes tells us about some of the stories she has unearthed from the archive, and looks at parallels with today’s #MeToo movement.

In March 1844, an enslaved woman named Fanny fled her master’s house in New Orleans. She did not flee alone, but ran with her child, a seven-year-old girl described as ‘mulatto.’

This simple description, applied to light-skinned, mixed-race African Americans, makes an important fact clear: Fanny’s daughter was fathered by a white man. Work by other historians, including Professor Emily West, indicates that the white man who was most likely to have fathered Fanny’s daughter was her master and the author of this advert, J.A. Braud.

Other sources tell us that enslaved women rarely attempted to escape slavery, often only using flight as a last resort in dire circumstances. Historian Stephanie Camp, for example, details other incidents in which threats against women’s virtue, or that of their daughters, drove them to flee bondage and seek freedom and escape. The detail in this advert, including the fact that she had lost her front teeth, suggests that Fanny ran away from a sexually abusive and violent slaveholder, and historians can infer that this sexual abuse likely drove Fanny to flee.

Traces of evidence

Reconstructing histories of slavery and sexual violence often relies on hints and fragments, like those contained in Braud’s advert. Enslaved people were mostly illiterate, had little to no access to the law, and often, much like Fanny, appear only in historical records as financial assets.

Historians rarely have access to full and detailed narratives of enslaved women’s lives, and even in those that do exist sexual violence is often remarked upon only in passing, or simply alluded to. Much like today, talking about sexual violence was considered shameful and uncomfortable, and women had little incentive to detail their suffering.

Seeking justice

After slavery was abolished in the United States in 1865, however, formerly enslaved women were given access to the law. Woman in their hundreds seized their new rights as citizens to speak out about their experiences of sexual violence, hoping to find justice for past wrongs.

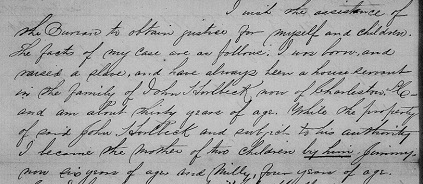

Flora Murphy, for example, complained to the federal government in 1866 about John Horlbeck, her former master. Horlbeck, Flora stated, had raped her while she was his property, and as a result she had given birth to two children. Flora hoped that the federal government would both recognise her claim to financial aid from Horlbeck, but also spoke out in the hope to correct any assumptions that might be made about her role in the relationship.

In her letter, Flora made it clear that Horlbeck was entirely to blame for her pregnancies, and so the financial burden of the children born as a result should fall on him. Flora simply stated: ‘while the property of said John Horlbeck and subject to his authority I became the mother of two children by him.’

Modern parallels

Flora was not alone in making her complaint to the federal government. Emboldened by their new legal status and by the actions of their neighbours, many formerly enslaved women came forward to complain about sexual violence they had suffered, and continued to suffer.

This wave of testimony has parallels with MeToo movement, in which the testimony of some prominent women on Twitter encouraged an outpouring of testimony across the globe. As formerly enslaved women learned in the 1860s, however, converting talk into change is incredibly difficult, and will take more than just a hashtag.

Liz Barnes will deliver her Fairbrother Lecture, ‘Women’s Voices: From slavery to the #MeToo movement at 7pm on 21 May 2019. The Fairbrother public lecture is delivered every year by a Reading doctoral researcher, giving them the chance to present their research to a wider audience.