Images made by Reading PhD students at work were selected for an exhibition at our annual doctoral research conference last month, featuring diverse subjects from earth worms to food bank workers. Here the researchers tell the stories behind their pictures.

Not to be sneezed at

Oliver Wilson, School of Archaeology, Geography & Environmental Science

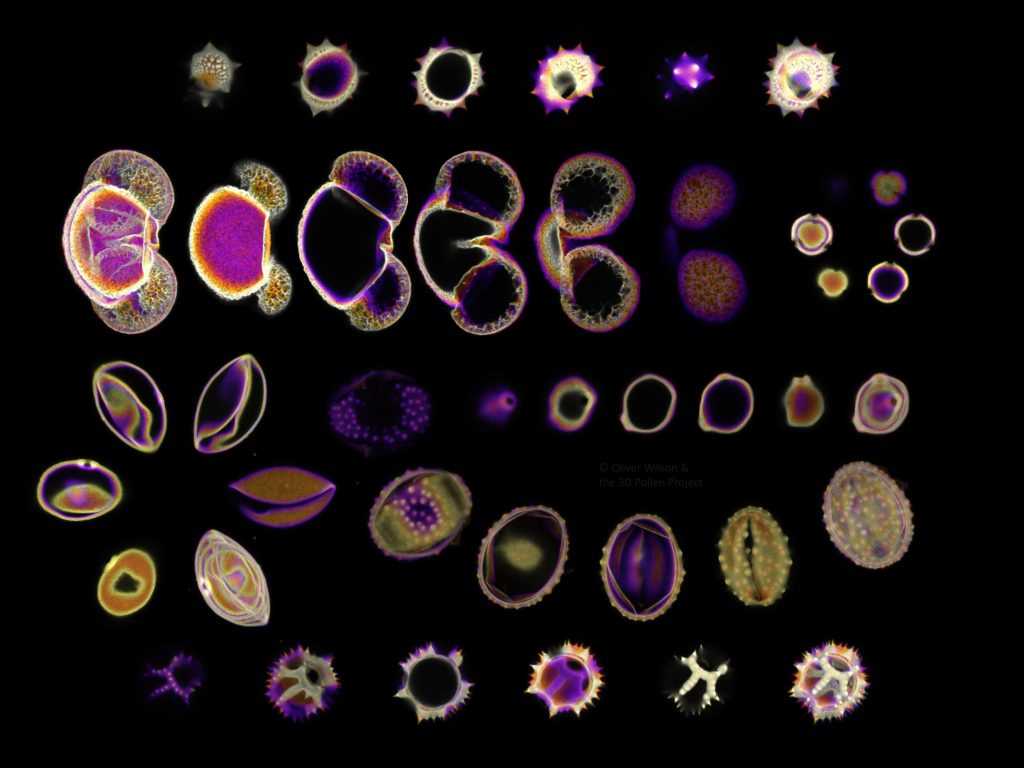

These images of pollen are part of the 3D Pollen Project and were produced from 480 individual cross-sectional scans taken with a confocal laser scanning microscope.

Being able to identify pollen under the microscope is important because, as well as causing hay fever, pollen grains are among the toughest things in nature and can survive for thousands or millions of years in lakes and bogs. Identifying pollen in mud layers of different ages shows how an area’s vegetation has changed through time – something I’m doing in my research into the past and future impacts of humans and climate change on one of Brazil’s most threatened forests.

In the image you can see pollen grains from (in reading order) ox-eye daisy, pine, meadowsweet, grass, knapweed, hazel, and autumn dandelion.

15,000 years in metres

Maria Rabbani, School of Archaeology Geography & Environmental Science

When humans transitioned from hunter gathering to farming deep in the Fertile Crescent (covering modern day Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria) approximately 11,500 years ago, they started to become masters of nature. My research examines pollen grains from this era which are preserved deep down in the ancient lake’s sediment, in order to assess the extent of human impact on the environment at that time.

This photograph captures an electric blue sky beneath which rest the magnificent Zagros mountains, surrounded by green plains as far as the eye can see. In the foreground, burly researchers work under a blazing sun to extract a 5.5m sediment core from the border of Lake Hashilan in Iran. This core contains within it secrets of the relationship between man and Mother Nature.

The Temple of Baalshamin

Luca Ottonello, School of Humanities

My research focuses on the effect of graphic reconstruction technologies on archaeology through time. I consider how these technologies change historical interpretation, with a case study based on the ancient city of Palmyra, sited in modern-day Syria.

This image shows my reconstruction of Palmyra’s Baalshamin temple. Digital reconstruction of ancient sites is often thought to be simple and fast – but that’s an erroneous assumption, partly arising from documentaries depicting considerably sped-up reconstructions.

In reality, such reconstructions require much unseen speculative work. Researchers must find solutions to a series of uncertain and unknown factors, bending reality to create a realistic reconstruction rather than a simple technical one, which would provide an immersive experience to audiences. By providing a step-by-step description of this process, I hope to reveal the compromises needed to reconstruct an area as complex as Palmyra.

Embodied Archaeology: A surveyor’s aide memoire

Katharine Whitaker, School of Archaeology Geography & Environmental Science

Here we can see my arms halfway through a day of analytical earthwork survey training. This took place at quarry pits in West Woods, Wiltshire, where Sarsen stones [sandstone blocks] were extracted up until the 1920s; one of the students was researching the use of this type of stone from prehistory to the present day.

We were recording complicated quarry pits while trying to get to grips with how to operate a Total Station Theodolite – an electronic/optical instrument used for surveying an archaeological site. In this photo I’m holding surveyors’ pins that are used to mark out archaeological features. The doodles on my arms represent the shapes of the quarry pits; these were to help novice surveyors to trace some of the quarry pits on the ground and record them with the theodolite without having also to refer to a paper sketch.

The secret life of a worm

Henny Folorunso, School of Archaeology Geography & Environmental Science

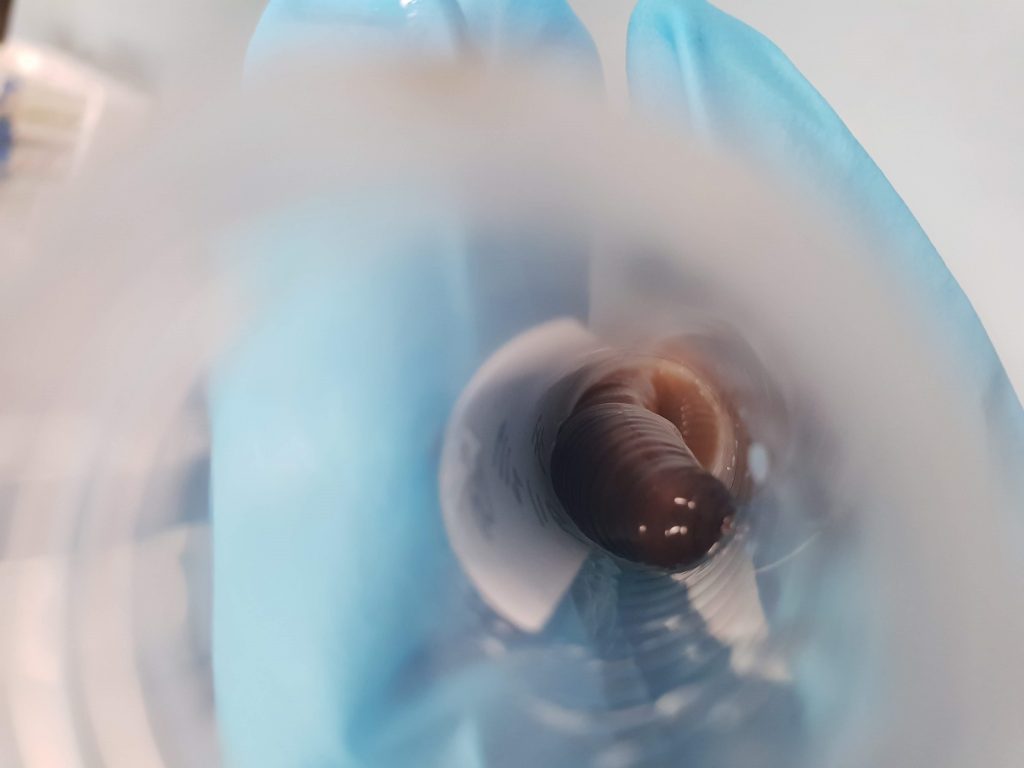

Earthworms may well be the heroes of the future. With the current global challenges of climate change and food security, it’s paramount that we understand how they contribute to functioning ecosystems if we are to harness them to deliver ‘ecosystem services’ such as carbon sequestration (‘locking away’ carbon in the soil) and increasing availability of nutrients in the soil to help plants grow.

There is lots of evidence to show that the interactions between earthworms and soil microorganisms are of vital importance to the process of organic matter decomposition, which affects the extent of carbon sequestration and nutrient release. However, the nature of these interactions is not clear because it is difficult to determine the relative contribution of each of the organisms involved. One of the aims of my PhD is to produce microbe-free earthworms for use in ecological studies so that we can see what happens when we take microbes out of the equation. This picture shows an earthworm whose interaction with microorganisms has been disrupted using antibiotics.

Motorbikes are for Men

Luisa Ciampi , School of Agriculture, Policy and Development

‘Motorbikes are for men’ is a phrase I heard over and over again during my research in Zimbabwe. My research project identifies the causes and results of the gendered nature of information in agriculture. One of the main channels of information to smallholder farmers is through agriculture extension agents (workers who deliver educational programs to assist people in economic and community development).

In the photo we can see four private extension workers supporting small-scale contract tobacco farming. Because agents have to ride on motorbikes for long periods of time, it is deemed to be a man’s job. We did meet a few women in the field who break the mould and spend hours riding around the bush on motorbikes, challenging the assumption that motorbikes (and therefore extensions jobs) are only for men.

‘She’s always got her head in a book.’

Charlotte Collingham , School of Biological Sciences

This is me and my lab buddy in the room where we spend most of our time. Our lab books are among the most important items for our PhDs since they contain all the information for our entire projects. A lab book should include all results, protocols, ideas, successes, failures and – most importantly – mistakes. Making mistakes is one of the best ways to learn. Trust me, I’d know. Having a tidy, well organised lab book is vital to a PhD.

Working on, and for, social justice

Sabine Mayeux, School of Archaeology, Geography and Environmental Science

As part of my fieldwork I volunteer at a community kitchen serving vulnerable and homeless people. Community initiatives such as this, coupled with the rising prominence of food banks, are symptomatic of growing food insecurity across the UK – but they are also spaces of hope and solidarity.

I am humbled to have been accepted and trusted by kitchen leaders and service users as I strive to write a thesis advancing our understanding of third-sector responses to poverty while honouring all those involved.

The University of Reading Graduate School’s annual doctoral research conference, which took place on 19 June, showcases the diversity of doctoral research undertaken at Reading. As well as the image competition, this year’s conference included competitions for research engagement; three-minute thesis; posters; poetry, rhyme and rap; and research films.

This year, conservation biologist Matt Greenwell won both the three-minute thesis competition and the research film competition. Watch his winning entries here: