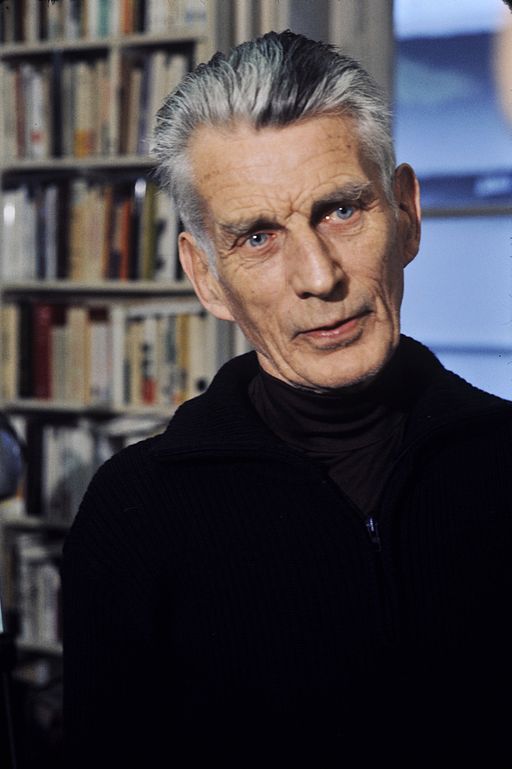

Manuscripts, notebooks and papers relating to world-famous novelist and playwright Samuel Beckett go on display at the University library today to mark its official re-opening. Beckett’s biographer Professor James (Jim) Knowlson tells the story of how the University of Reading became home to the biggest collection of Beckett materials in the world.

In 1969, Samuel Beckett won the Nobel Prize for Literature – ‘for his writing, which – in new forms for the novel and drama – in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation’.

The following year, Dr Jim Knowlson moved to a Lectureship at Reading from the University of Glasgow, where he had been teaching 18th century French Literature and Thought, and Modern Drama.

Jim had what he now describes as a ‘crazy idea’ – to put on an exhibition dedicated to the new Nobel Laureate’s work. There was only one problem: at that time, the University only had six of Beckett’s books.

Youthful enthusiasm

Not to be thwarted by having very little to exhibit, Jim decided that he would go ahead. “Enthusiasm can get one into terrible hot water,” he says.

“We borrowed things from all over the place. I went to Paris [where Beckett had lived for some 50 years] because I knew an Irish friend of his.”

Through their mutual friend, Jim managed to get Beckett’s telephone number and he called him to request the loan of some items for the exhibition.

“My hand was trembling as I held the ‘phone. But I immediately felt at ease because I’d been told by our mutual friend that he hated being treated like a great man. Consequently we discovered we were both very interested in sport. So I would talk about cricket and David Gower’s cover drive, or ‘Beefy’ Ian Botham.”

Having found some common ground with sporting chat, Beckett agreed to lend some of his personal papers, and provided Jim with information on friends and publishers who would help him acquire material.

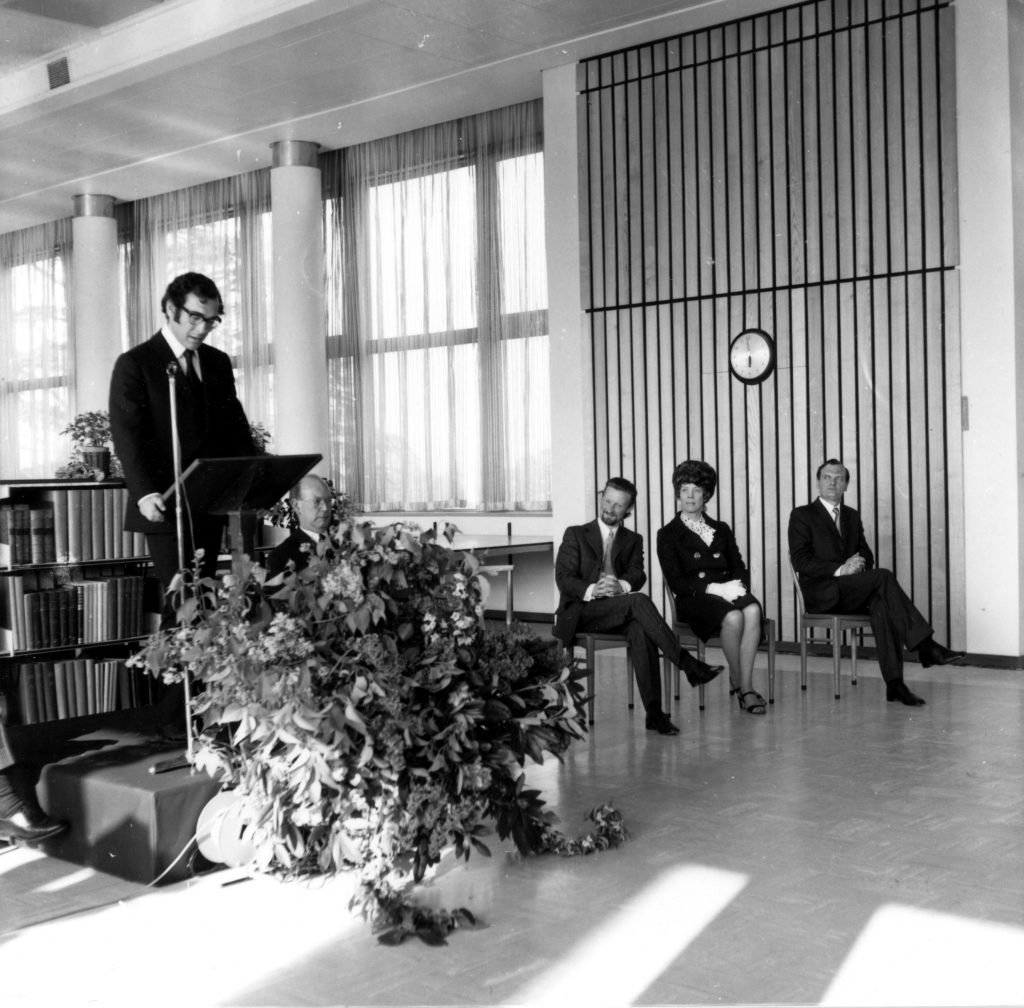

“He lent us a lot of manuscripts. Lots of friends lent us manuscripts. It had a lot of momentum – once one friend is helping you then everyone else felt that they had to help. So we had a big exhibition which then toured Europe and America – in photographic form, at least,” says Jim.

In 1971, the University mounted an exhibition of Beckett’s work in the University Library, opened by Beckett’s friend and fellow dramatist Harold Pinter.

A collection is born

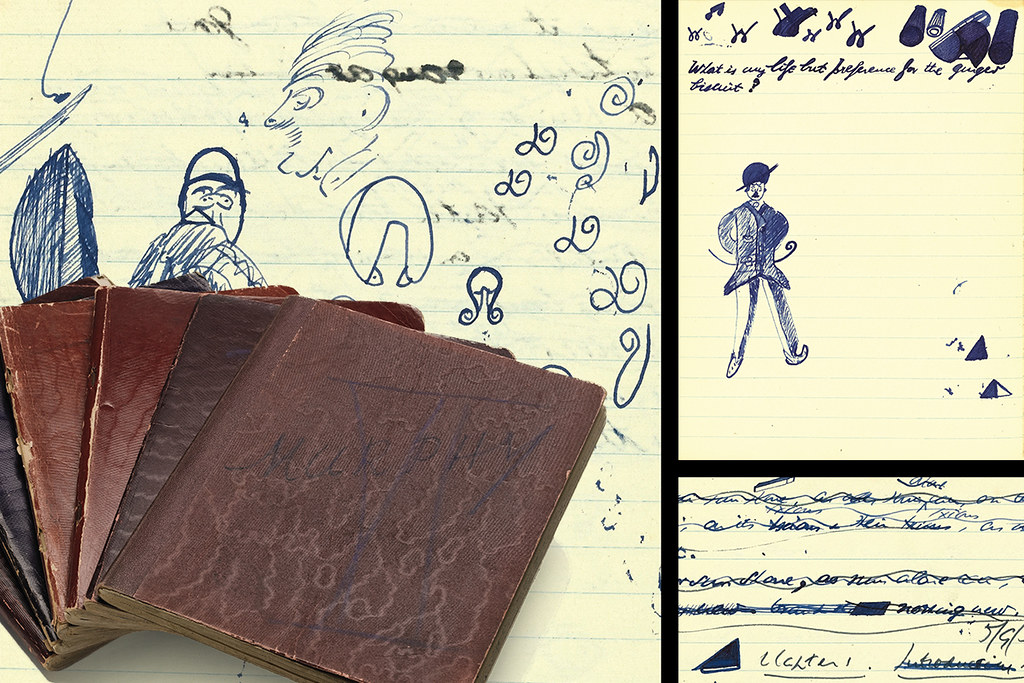

After the exhibition, when the University proposed setting up a dedicated Beckett collection, Beckett suggested that Reading should keep some of the manuscripts.

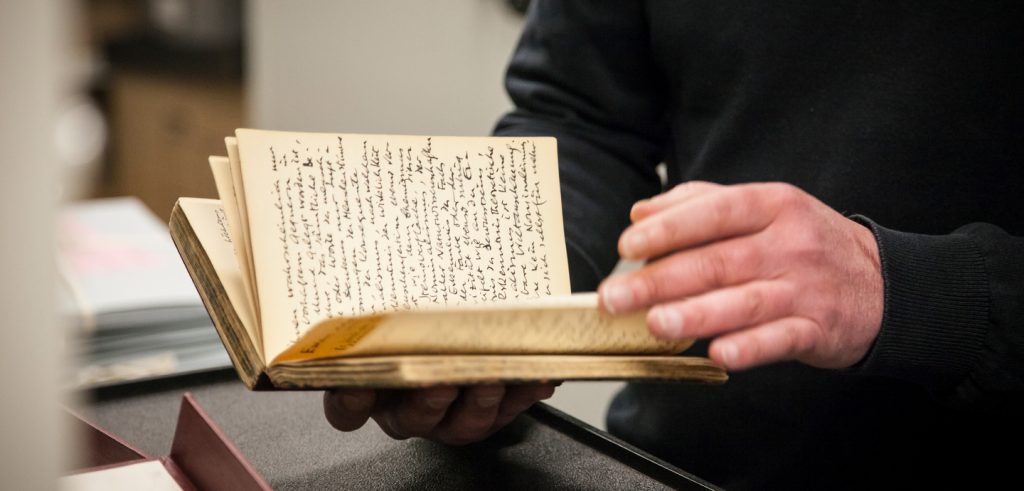

“Every time I went to Paris after that date he would say ‘I’ve got something for you’ and he would pull out a package or a small suitcase or a Galerie Lafayette bag full of books, manuscripts, documents all kinds of things like that,” explains Jim. “And over the years we developed this very large and very rich, both scholarly and financially, collection of Beckett material.”

This collection formed the basis of what became the Beckett archive. In the late 1980s, Jim established it as a charitable trust called the Beckett International Foundation, which now holds the largest and most valuable collection of Beckett manuscripts in the world.

Firm friends

Jim went on to be a close friend of Beckett, regularly having dinner and long chats with him. Ultimately, after 18 years of friendship and writing 12 books and editions about his theatre, he became his authorised biographer in 1989.

Jim says, that for him at least, Beckett’s reputation as an aloof, private man was unfounded:

“He was witty, very sociable, very amiable, talked to you often about your family and what you were doing rather than what he was doing. But gradually, over the years, he would talk about what he was doing, what he was writing or translating, the actors he was working with, and so on. This idea that he never talked about his work did not conform to my experience. What he never did was to offer any meanings.”

“Beckett doesn’t just take you in. He takes you out, to look at other things he was influenced by: music, art, philosophy. [As his biographer] I became an auto-didact, teaching myself in order to understand what was happening in his work,” says Jim.

“Although he was often thought of as ‘the poet of nothingness’, I came to realise gradually that, as well as what he had read or paintings that he had seen and admired, his life and physical, concrete things were very important. But I also recognised that you couldn’t build too obvious bridges between his life and his work.”

Following the 1971 exhibition, The Beckett Collection continued to grow until it was the largest in the world and was officially designated as an Outstanding Collection. The University established the Beckett International Foundation and, more recently, the Beckett Research Centre, which has funded a series of Creative Fellowships. The first was acclaimed author Eimear McBride, who wrote a series of blog posts for Connecting Research on her experience, and the most recent Fellows are the composer Tim Parkinson and the novelist and editor Robert McCrum.

The Samuel Beckett exhibition at the University Library runs from Monday 24 February until 15 June 2020.

Professor Jim Knowlson is Emeritus Professor of French Literature at the University of Reading. Having completed both undergraduate studies and his PhD at Reading, he returned here from the University of Glasgow to a Lectureship in French in 1969 and became a Personal Professor of French in 1981. He was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters by the University of Reading in 2006, became an Officier dans l’Ordre des Palmes Académiques in 2011 and received an OBE ‘for his services to literary scholarship’ in 2014.

This blog post was written based on a 2003 Theatre Voice interview with Jim Knowlson – listen to the full interview.