The publishing industry decides what gets published and determines whose voices get heard. The books we read are shaped by the people who produce them, and a publisher’s archive is full of stories behind the making of books. Here Nicola Wilson and Helena Clarkson reflect on some of the hidden tasks and detective trails involved in setting up the Modernist Archives Publishing Project.

Publishers’ archives are big, messy beasts. Where they are preserved (and many have been lost), they can be difficult to navigate and are often split, spread far and wide. We founded the Modernist Archives Publishing Project (MAPP) to democratise access to archives that are fragmented across the world, and to create an enhanced archival experience through virtue of the digital: bringing together materials more coherently to tell the story of a book’s lifecycle.

Our data model follows what book historians know as the ‘communications circuit’ – the 360 degree journey of a book from submission to the publisher to the hands of the reader. The MAPP website preserves and contextualises aspects of the publishing process which may be little known to outsiders (readers’ reports, proofs and editorial discussions, marketing materials and readership data) and displays these processes in relation to books (editions, dust jackets, full-text scans) and the people and businesses involved in making and selling them (authors, editors, artists, bookshops).

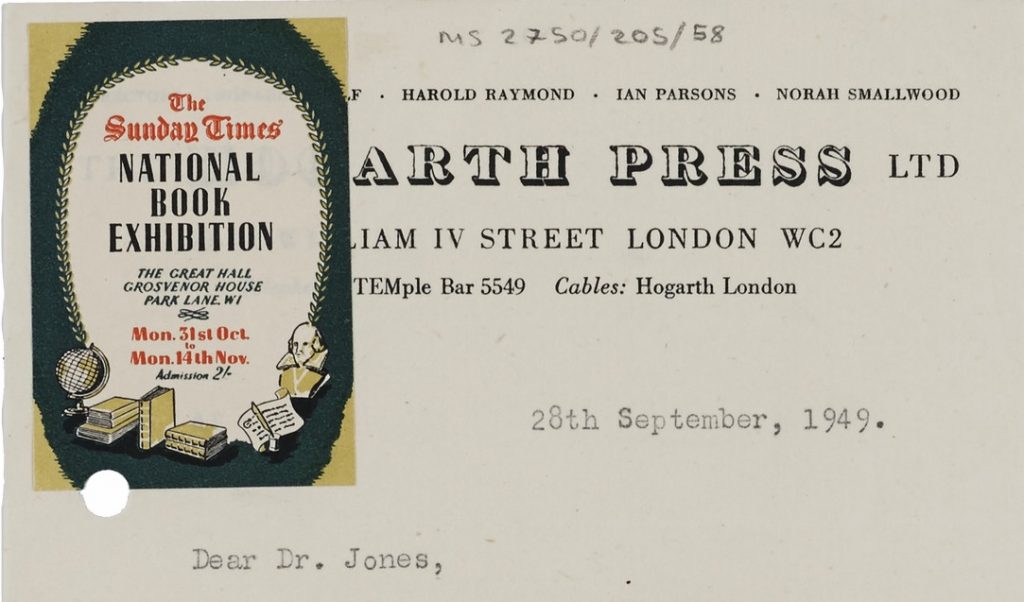

Our pilot case study focusses on the Hogarth Press, publishing house of writers Leonard and Virginia Woolf, set up in 1917 and independently owned until its incorporation into Chatto & Windus in 1946. MAPP opens up the Hogarth Press archive at the University of Reading to undergraduate students as well as public audiences around the world. MAPP is a transatlantic team and so far we have included materials that complement those held by Reading with resources from the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas; Smith College in Massachusetts; Bruce Peel Library at the University of Alberta; the E.J. Pratt Library in Toronto; and the Washington State University library.

Funding from the University’s Research Endowment Trust Fund enabled MAPP to employ Helena Clarkson, a recently qualified graduate in Archives and Records Management, to work on digitisation, metadata, and the complex permissions process involved in making unpublished archival material open access.

Helena says: “The participatory nature of MAPP, and the fact that it aims to break down barriers regarding archival access, are just two of the facets that interest me. Digital curation is a vast landscape in the archival world, and as the project has been progressing, it has enabled me to learn skills and gain experiences that are new to me, for example: working with content management systems and being part of a transatlantic team who all contribute to MAPP’s evolving work processes. I have also developed my knowledge on UK copyright; for me, early in my career this is invaluable.”

A lot of copyright work for MAPP involves tracing permissions. Penguin Random House UK (now corporate owner of the Hogarth Press imprint and legal depositors of the archive) have granted permission to display letters and financial records written by individuals ‘at work’, but there can be multiple rights holders in a publisher’s archive. Copyright in a letter resides with the writer of the letter, not the recipient, so this means tracing literary estates of authors, as well as publishers, printers, and solicitors (to name a few).

Even though many of these organisations have long since ceased to trade, the barrier for MAPP is that the material we are uploading is unpublished, and as a general rule, most of this copyright won’t expire until the year 2039. There is some detective work involved: searching family trees, finding out who deposited collections in archives, researching who now owns businesses or publishers’ imprints. Sometimes the copyright holder remains unknown or difficult to trace, so we have applied for a UK government ‘Orphan Works License’ to publish material online. In other instances, there may be Crown copyright involved, in which case we need to be aware when we can use an Open Government Licence. Sometimes organisations will only grant a licence for several years or will want to provide the image on their own terms.

Overall, most estates and companies have been supportive, and MAPP is beginning to build its content as more permissions are sought.

Going back to the old idea of publishers as gatekeepers, some of this tracing can be frustrating. But we need to acknowledge and make visible the behind-the-scenes research that goes on to preserve author’s legacies and mitigate the potential risks involved in publishing copyrighted material, meaning ultimately that our audience pass through far fewer obstacles before being able to view archival content online.

In the rush to make more materials available online because of the Covid-19 pandemic, established digital archives like MAPP have an important role to play. If we are to make archive and collections more widely available, we need to acknowledge the challenges of getting unpublished material responsibly and sustainably into the public domain. Our next aim is to incorporate more publisher’s archives into MAPP, so users can see what Alison Rukavina calls the ‘tangled networks’ of books, and the interconnections between writers, editors, publishers and artists in the book world.

Nicola Wilson is Associate Professor of Book and Publishing Studies in the Department of English Literature and co-director of UoR’s Centre for Book Cultures and Publishing. Helena Clarkson is the Project Archivist for MAPP, based in the University Museums and Special Collections Services.

This was one of five research projects which received funding for a pilot phase from the University Research Endowment Fund in January 2019. The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada is funding the continuation of this work.